Social Security Reform Proposal: Why Do Estimates of the 2100 Act’s Impact Differ?

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Analysts score the bill similarly, but financial effects vary dramatically.

A reporter called recently with a question about the impact of the Social Security 2100 Act, proposed by Representative John Larson (D-CT and Chairman of the House Ways and Means Social Security Subcommittee) and others. Apparently, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and the Social Security Administration’s Office of the Chief Actuary (OCACT) show this legislation having very different impacts on the financing of the program. OCACT says the 2100 Act would completely eliminate the shortfall and keep the program solvent for 75 years, while the latest from CBO has the trust fund hitting zero in 2036.

This sounded crazy to me. How could it be that the same provisions produced such different outcomes.

Let’s look first at the 2100 Act. This legislation retains – and even slightly enhances – benefits and substantially increases the income rate. On the benefit side, it offers four enhancements:

- Uses the Consumer Price Index for the Elderly (CPI-E), which rises faster than the CPI-W, to adjust benefits for inflation.

- Raises the first factor in the benefit formula from 90 to 93 percent, which would slightly raise replacement rates for all.

- Increases thresholds for taxation of benefits under the personal income tax, which would allow middle-class workers to keep more of their benefits.

- Increases the special minimum benefit for those with very low earnings.

To pay for these benefit enhancements and, more importantly, to eliminate the 75-year deficit, the legislation increases income to the program in two significant ways:

- Raises the combined OASDI payroll tax of 12.4 percent by 0.1 percentage point per year until it reaches 14.8 percent in 2043.

- Applies the payroll tax on earnings above $400,000 and on all earnings once the taxable maximum reaches $400,000, with a small offsetting benefit for these additional taxes.

Both OCACT and CBO have “scored” this legislation and their results are very similar. CBO estimates that the legislation would improve Social Security’s actuarial deficit by 1.2 percent of GDP, whereas OCACT projects an improvement of 1.1 percent. That is, CBO actually projects a slightly larger impact of the 2100 Act, because it projects a smaller share of earnings subject to payroll taxation under current law and, therefore, more above the $400,000 level that would be taxed under the legislation. The real question, however, is – with the two estimates of the impact of the legislation so close – why such a different effect on the program’s finances?

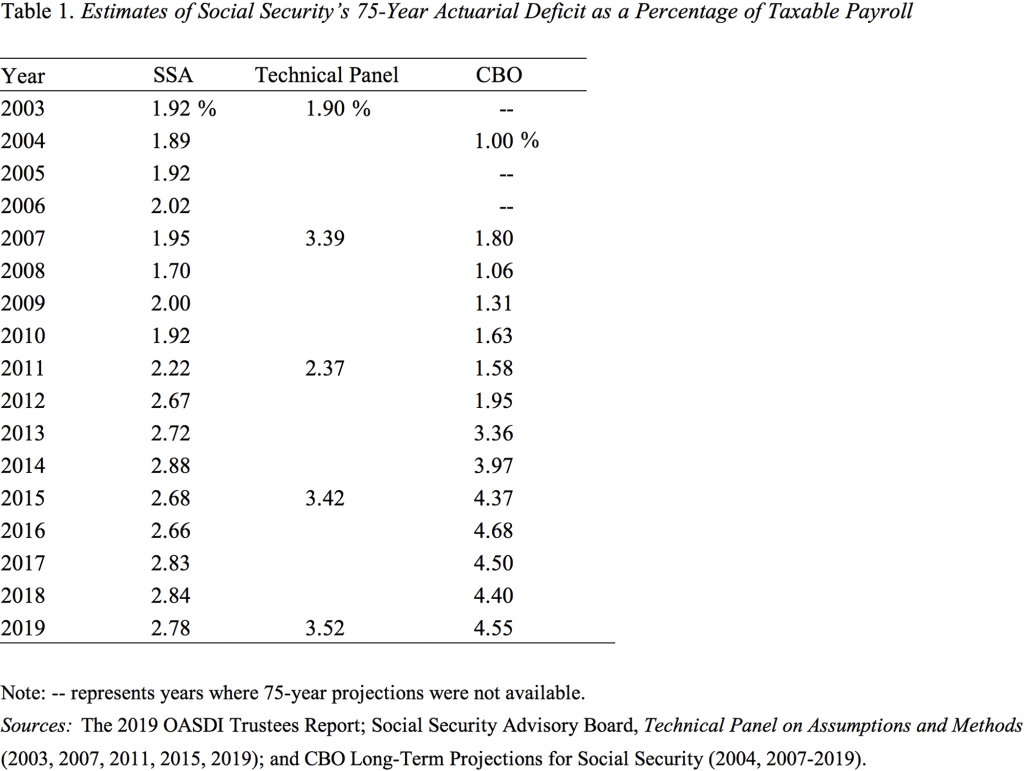

The answer rests on the two agencies’ estimates of the size of Social Security’s actuarial deficit under current law. In their 2019 annual report, the Social Security Trustees project a 75-year deficit equal to 1.0 percent of GDP; CBO projects a deficit of 1.5 percent of GDP. The CBO projection assumes greater longevity; continued widening of earnings inequality (and therefore a smaller share of earnings subject to the payroll tax); lower real interest rates; and lower average annual growth in GDP.

What to believe? Table 1, which includes projections from Social Security’s Trustees Reports, Social Security’s quadrennial Technical Panels of outside experts, and the CBO, might be helpful in making a judgment. The Technical Panels’ assessments have been closer to the projections from the Social Security Trustees than those from CBO, and the Social Security Trustees’ estimates have bounced around a lot less than CBO’s. So I’m sticking with the Trustees’ estimates.