Social Security Report Shows Uptick in 75-Year Deficit, No Change in Trust Fund Depletion Date

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

COVID-19 will impact this projection, but probably not significantly.

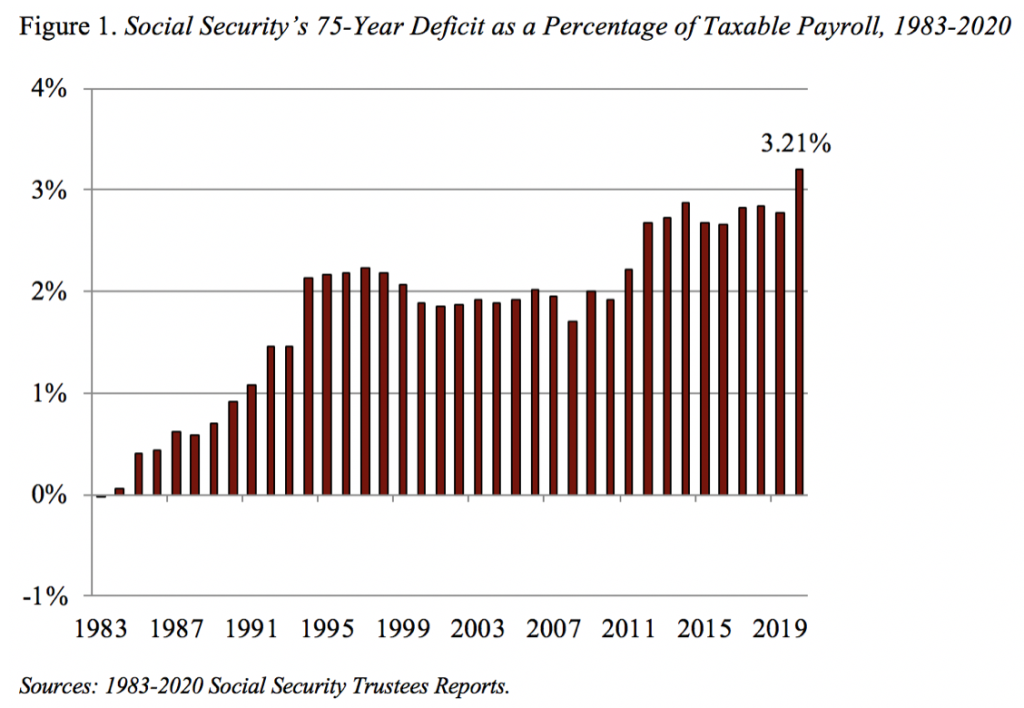

The 2020 Trustees Report, which was prepared before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, shows an increase in the program’s 75-year deficit from 2.78 percent to 3.21 percent of taxable payroll (see Figure 1). The depletion date for the trust fund remains at 2035.

What does a deficit of 3.21 percent of taxable payrolls mean? That figure means that if payroll taxes were raised immediately by 3.21 percentage points – roughly 1.6 percentage points each for the employee and the employer – the government would be able to pay the current package of benefits for everyone who reaches retirement age at least through 2094.

Any package, however, that restores balance only for the next 75 years will show a deficit in the following year, as the projection period picks up a year with a large negative balance. Realistically, eliminating the 75-year shortfall should probably be viewed as the first step toward long-run solvency.

What does exhaustion of the trust fund mean? The exhaustion of the trust fund does not mean that Social Security is “bankrupt.” Payroll tax revenues keep rolling in and can cover about 75 percent of currently legislated benefits over the remainder of the projection period. Relying on only current tax revenues, however, means that the replacement rate – benefits relative to pre-retirement earnings – for the typical age-65 worker would drop by more than 25 percent.

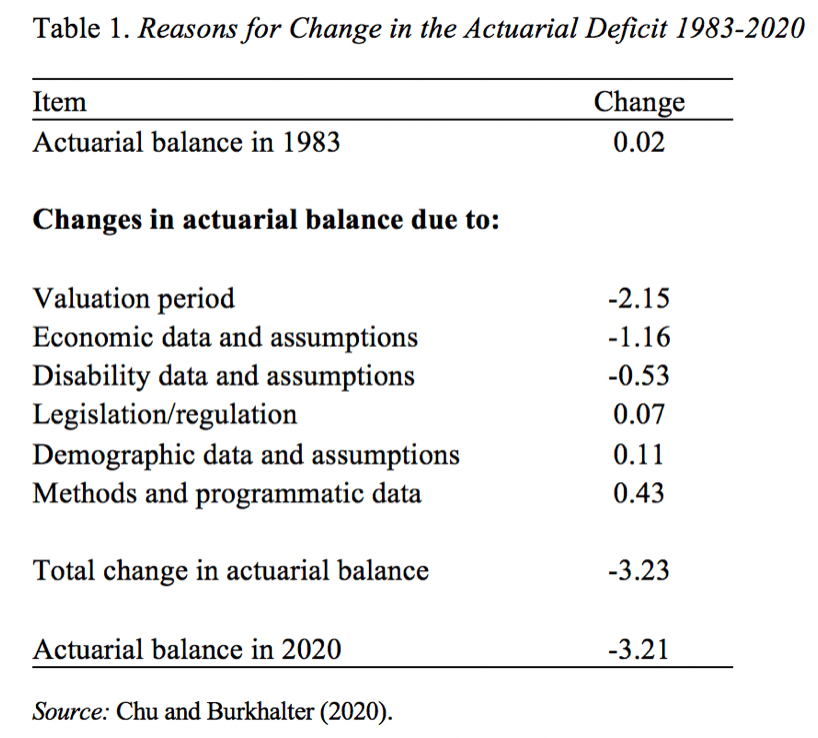

How did we get to a projected deficit in 2020 from a projected 75-year surplus in 1983? Leading the list is the impact of changing the valuation period (see Table 1). That is, the 1983 Report looked at the system’s finances over the period 1983-2057; the projection period for the 2020 Report is 2020-2094. Each time the valuation period moves out one year, it picks up a year with a large negative balance. A worsening of economic assumptions – primarily a decline in assumed productivity growth and the impact of the Great Recession – has also contributed to the increase in the deficit. Offsetting the negative factors has been a reduction in the actuarial deficit due to changes in demographic assumptions – primarily higher mortality for women – and some changes due to legislation and methodology.

Why did the deficit increase between 2019 and 2020? The increase is attributable to four main factors: 1) the repeal of the tax on high premium health plans, resulting in lower earnings and payroll taxes (as total compensation shifts more toward health benefits); 2) a lower assumed total fertility rate, resulting in a higher ratio of retirees to workers; 3) lower inflation, producing an immediate reduction in earnings and payroll taxes and only a delayed reduction in benefits; and 4) a lower interest rate, which means less discounting of large future deficits.

The bottom line is that while the deficit is larger, Social Security has once again demonstrated its worth during these tumultuous times, when – in the face of economic collapse – it has continued to provide steady income to retirees and those with disabilities. The program faces a manageable financing shortfall over the next 75 years, which should be addressed – once COVID-19 is under control – so that Americans will have confidence that the program will be able to pay the full amount of promised benefits.