Social Security Will Provide Less Under Current Law

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Social Security is the backbone of the nation’s retirement income system. Policy experts have focused on alternative ways of eliminating Social Security’s 75-year financing gap, but lost in the debate is the fact that even under current law Social Security will provide less retirement income relative to previous earnings than it does today. Combine the already legislated reductions with potential cuts to close the financing gap, and Social Security may no longer be the mainstay of the retirement system for many people.

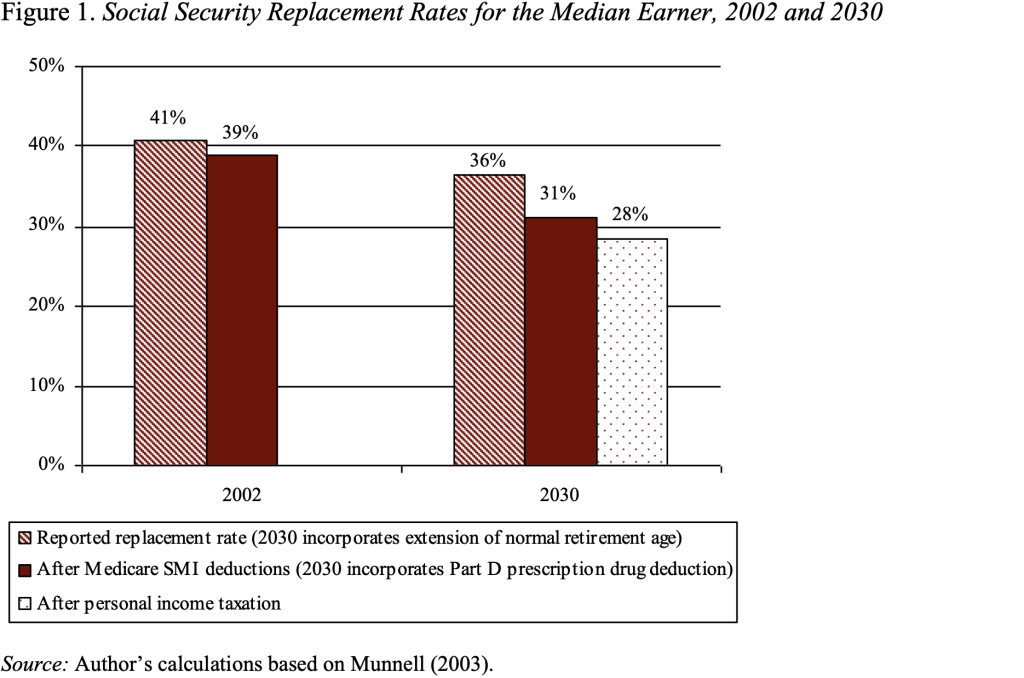

In 2002, the frequently quoted replacement rate for the “medium earner” who earned about $41,000 and retired at age 65 was 41 percent; that is, Social Security benefits were equal to 41 percent of the individual’s previous earnings. Under current law, three factors will reduce this replacement rate: 1) the extension of the Full Retirement Age; 2) the increase in Medicare premiums; and 3) the taxation of Social Security benefits.

First, under current law, the Full Retirement Age is scheduled to increase from 65 for those reaching 62 in 2000 to 67 for people reaching age 62 in 2022. This increase is equivalent to an across-the-board benefit cut. For those who continue to retire at age 65, this cut takes the form of lower monthly benefits; for those who extend their worklives, it takes the form of fewer years of benefits. Thus, as reported in the Social Security Trustees Report, the replacement rate for the medium earner will drop from 41 percent to 36 percent for people who retire at age 65 in 2030.

The second development that will affect future replacement rates is the rising cost of Medicare. Medicare premiums, which are automatically deducted from Social Security benefits, are scheduled to increase from 5 percent of benefits for someone retiring in 2002 to 12 percent for someone retiring in 2030.

The third factor that will reduce Social Security benefits is the extent to which they are taxed under the personal income tax. Under current law, individuals with less than $25,000 and married couples with less than $32,000 of “combined income” do not have to pay taxes on their Social Security benefits. (Combined income is adjusted gross income as reported on tax forms plus nontaxable interest income plus one half of Social Security benefits.) Above those thresholds, recipients must pay taxes on either 50 or 85 percent of their benefits. In 2002, only 20 percent of people receiving Social Security had to pay taxes on their benefits, so median earners typically did not pay any taxes. But the thresholds are not indexed for growth in average wages or even for inflation so, by 2030, as real benefits and other income increases, many medium earners will pay tax on half of their benefits.

The bottom line is that the net Social Security replacement rate for the medium earner will decline from 39 percent in 2002 to 28 percent in 2030 under current law (see Figure). Policymakers need to be aware of this fact when they consider how much of the 75–year financing gap should be closed by benefit cuts and how much by tax increases.