Social Security’s Deficit Increase: Why? What Now?

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

The 2012 Trustees Report shows a significant increase in the program’s 75-year deficit from 2.22 percent to 2.67 percent of taxable payroll and an advance in the date of trust fund exhaustion from 2036 to 2033. Why did the deficit increase? What are the implications?

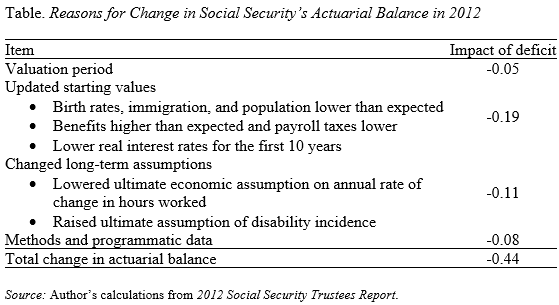

The increase in the deficit primarily reflects three developments: 1) moving the valuation period ahead one year; 2) recalibrating 2012 demographic and economic variables to reflect the impact of the slow recovery from the recession; and 3) changing two sets of long-run assumptions. The table summarizes the changes.

Social Security’s deficit automatically increases each year by about 0.05 percent as the valuation period changes. That is, the 2011 Report looked at the system’s finances over the period 2011-2085; the projection period for the 2012 Report is 2012-2086. Each time the valuation moves out a year, it picks up a year with a large negative balance, which increases the 75-year deficit.

The weak economy also required the Trustees to update some demographic and economic factors that have been adversely affected by the economy. On the demographic side, birth rates, legal immigration, and starting population all turned out to be lower than expected, so the Trustees updated the 2012 values and the way these starting values transitioned to the ultimate assumptions. On the economic side, they also updated starting values for benefit levels, which were higher than expected because of the 2011 cost-of-living adjustment, and for payroll taxes, which were lower than expected because of the weak economy.

In terms of changes to long-run assumptions, the Trustees made changes in two areas. First, on the economic front, the Trustees lowered the ultimate assumption regarding the rate of change in hours worked to better reflect the habits of an aging workforce and a projected increase in the demand for leisure as living standards rise. Second, in terms of the disability program, the Trustees increased the ultimate assumption about incidence of disability to better reflect the increasing trend of the last 10 years. Finally, methodological changes also increased the actuarial deficit.

While the deficit is larger and the date of exhaustion nearer, the story remains the same. The program faces a manageable financing shortfall over the next 75 years, which should be addressed soon to restore confidence in the nation’s major retirement program and to give people time to adjust to needed changes.