State and Local Pension Plans Have Shifted Towards “Alternative Investments”

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

An early look suggest that these investments have neither increased returns nor reduced volatility.

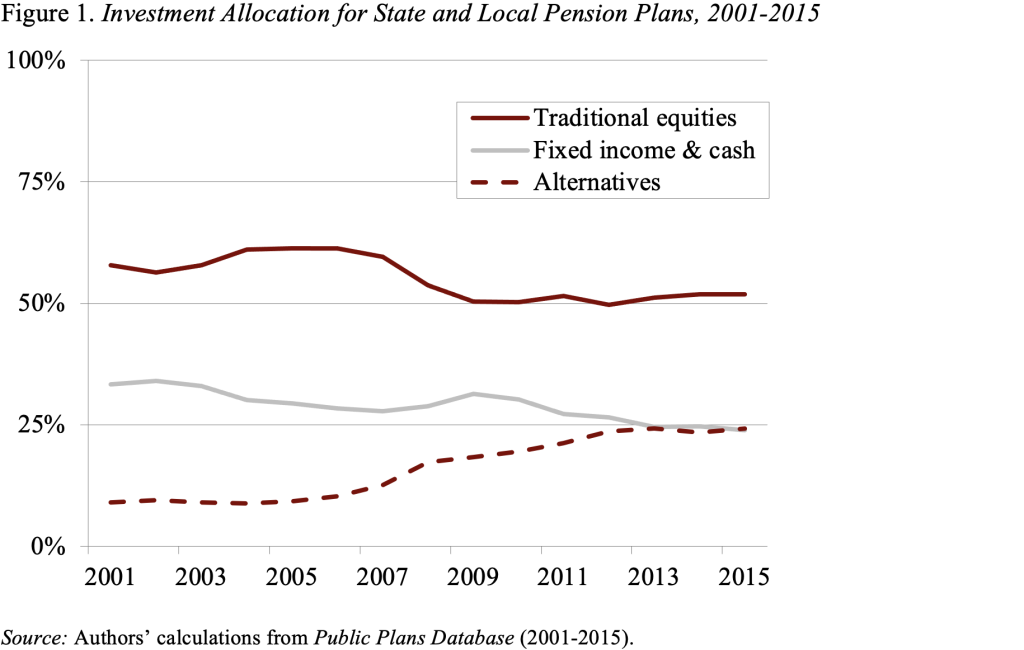

My colleagues – JP Aubry and Anqi Chen – and I are just completing a study on the impact of changes in the investment portfolios of state and local pension plans. Since the financial crisis, public pension plans – like other large institutional investors – have moved a significant portion of their portfolios into investments outside of traditional equities, bonds, and cash. These alternative investments include a diverse assortment of assets – private equity, hedge funds, real estate, and commodities. Between 2005 and 2015, the allocation to alternatives more than doubled (from 9 percent to 24 percent) (see Figure 1). This shift reflects a search for greater yields than expected from traditional stocks and bonds, an effort to hedge other investment risks, and a desire to diversify the investment portfolio.

The focus of our study is how the shift towards alternatives has affected investment returns.

An ideal analysis would compare each plan’s investment outcomes to its investment strategy. However, given that detailed historical returns are not available for each individual asset in each plan portfolio, we estimate four equations that test the relationship of alternative investments to observed portfolio returns and volatility. Our sample includes 160 state and local plans over two periods – 2005-2015 and 2010-2015.

The first equation relates the average after-fee portfolio returns to the percentage of the portfolio invested in alternatives and some control variables. The results show that holding an additional 10-percent of the portfolio in alternatives reduces the after-fee return by between 30-45 basis points compared to investing in equities.

One problem with the first equation is that it treats alternatives as a single asset class – which they clearly are not. Therefore, the second equation relates the average portfolio returns to holdings in the four major alternative asset classes: private equity, hedge funds, real estate, and commodities. The results show that the negative relationship between alternatives and overall portfolio returns stems primarily from hedge funds. None of the other three asset classes, however, had a statistically significant positive effect on returns.

Plans, however, may care about more than simple returns. Hence, the third regression relates holdings in alternatives to the volatility (standard deviation) of overall portfolio returns. The results show that, as a group, alternatives did not have a statistically significant effect on volatility in either the 2005-10 or 2010-15 period.

A fourth equation shows that the reason for the “no-effect” result was that the reduction in volatility from hedge funds is offset by an increase in volatility from real estate and commodities.

Our conclusion is that while the focus on returns and volatility may be too narrow and the time periods analyzed too short to draw any definitive implications – the relationship between alternatives and public plan performance merits further analysis.