Tax Bill’s Inflation Adjustment Is Sensible

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

But it shouldn’t be used as a precedent for Social Security.

Both the House and Senate tax cut proposals change the measure of inflation used to adjust the income thresholds in the tax schedule. This shift to a “chained” consumer price index (CPI), which makes sense on the tax side, has also been proposed in the past for indexing Social Security benefits after retirement, where the case is somewhat less compelling.

On the tax side, without indexing, the tax rate on earnings would increase over time even if “real” (inflation-adjusted) earnings were not rising. Indexing by the CPI ensures that workers whose earnings rise solely in response to inflation would not experience an increase in their tax rates.

Experts agree that the measure of the CPI currently used to adjust the tax brackets overstates inflation; therefore, the brackets rise too rapidly, which reduces the tax take. The overstatement occurs because the current index does not fully reflect the extent to which people can maintain the same level of satisfaction by substituting among products when the price rises.

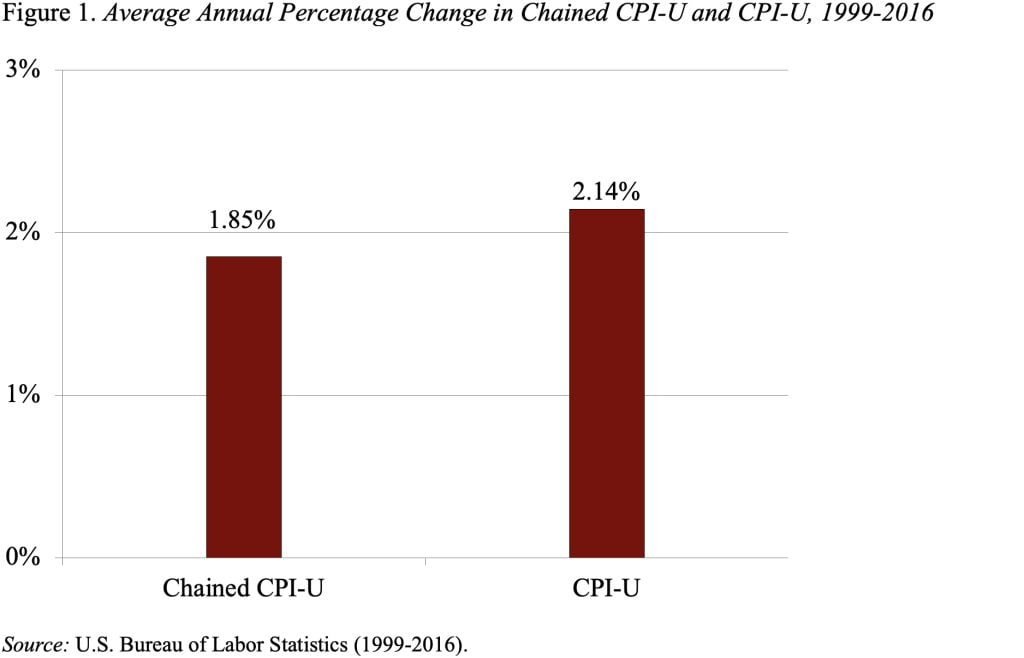

Figuring out how consumers might adjust their spending in response to price changes was originally a daunting task, but economists and statisticians devised an index that could account for consumer substitution. The Bureau of Labor Statistics publishes data for this “chained” index back to December 1999. Between December 1999 and December 2016, the chained index rose at an annual rate of 1.9 percent – about 0.3 percent less than the current CPI (see Figure 1). Shifting to a chained CPI is a sensible thing to do on the tax side to avoid an unnecessary loss of revenues.

Such a shift would also make sense for determining the annual cost-of-living adjustment applied to Social Security benefits if the current price index used for this purpose (the CPI-W) adequately reflected the cost increases faced by the elderly. Unfortunately, we do not have a properly constructed index for older Americans to serve as a basis of comparison.

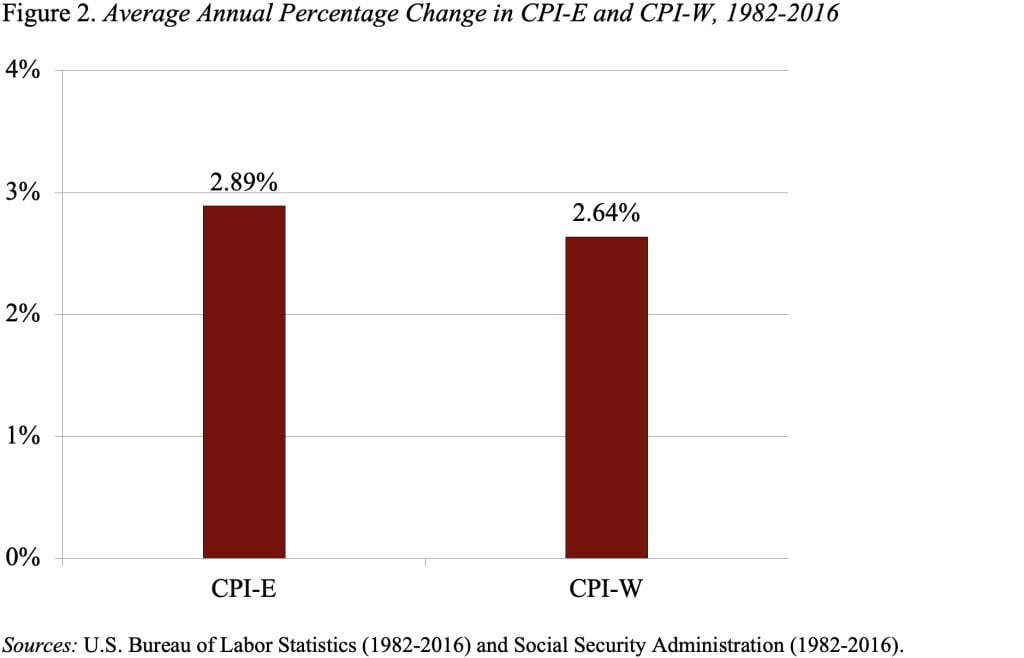

A true index for the elderly would require collecting price quotes on the products that older people buy at the type of retail outlets they frequent. It could be that older people with ample time shop at Costco and enjoy lower prices and less inflation than the rest of the population or they could be limited to shopping at their neighborhood 7/11 store and face higher prices and more inflation. Instead of constructing an entirely new index, however, the BLS only has the resources to reweight the elementary indexes in the CPI to reflect the expenditure patterns of older consumers. While it is impossible to say with certainty without a properly constructed index for older Americans, the re-weighted index for the elderly (CPI-E) – which has data back to 1982 –suggests that the index currently used to adjust Social Security benefits understates the rate of price increase by about 0.3 percent (see Figure 2).

So, a fair discussion of the Social Security cost-of-living adjustment should acknowledge the offsetting biases of the understatement of inflation due to not recognizing the spending patterns of the elderly and the overstatement of inflation due to not accounting for substitution.

The main point is that adopting a “chained” CPI on the tax side should not be used as a precedent for Social Security.