The Economics of Being Black in the U.S.

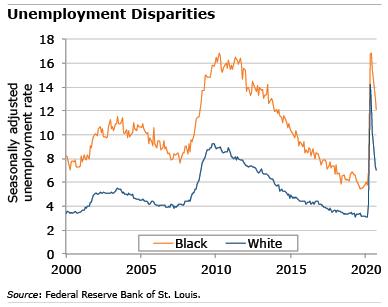

The COVID-19 recession demonstrates an axiom of economics. Black unemployment always exceeds the rate for whites, the spikes are higher in recessions, and, in a recovery, employment recovers more slowly.

A record number of Black Americans were employed in 2019. But when the economy seized up in the spring, their unemployment rate soared to 17 percent, before floating down to a still-high 12.1 percent in September. Meanwhile, the white unemployment rate dropped in half, to 7 percent.

The much higher peaks in the unemployment rate for Blacks than whites and the slower recovery are baked into the economy.

This phenomenon occurred during the “jobless recovery” from the 2001 downturn. When the economy had finally restored all of the jobs lost in that recession, the Black jobless rate remained stubbornly higher.

And after the 2008-2009 recession, as the University of California, Berkeley’s Labor Center accurately predicted at the time, Black unemployment hovered at “catastrophic levels” longer than the white rate did. This disparity is now the issue in the COVID-19 recession.

Geoffrey Sanzenbacher, a Boston College economist who writes a blog about inequality, gives three interrelated reasons for Black workers’ higher unemployment rates.

First, “The U.S. still has a tremendous amount of education inequality, and the unemployment rate is always higher for people with less education,” he wrote in an email. Despite the big strides by Black men and women to obtain college degrees, roughly 30 percent have degrees, compared with more than 40 percent of whites, he said.

Second, Black workers without degrees are vulnerable because they are more likely to earn an hourly wage. An hourly paycheck means that a company can cut costs by simply reducing or eliminating a worker’s hours. “It’s much easier to lay off hourly workers, whose employment is more flexible by nature, than salaried workers,” Sanzenbacher said.

This past spring, Black workers disproportionately lost their jobs because they are more heavily represented in service and luxury industries like travel and hotels – these are often hourly jobs that don’t require a college education. The devastation to travel-industry workers is apparent in the jets parked on airport tarmacs and cruise ships floating idly off the coast of England.

Third, discrimination means the Black jobless rate is slower to rebound, Sanzenbacher said. He cited a study in the American Economic Review showing they would have to apply for 34 jobs to have a 90 percent shot at being called in for an interview – whites would need to file only 22 job applications.

As the COVID-19 restrictions eased, hiring has picked up. But the unemployment rate for whites is falling much faster than it is for Blacks – just as it always does.

Read more blog posts in our ongoing coverage of COVID-19.

Squared Away writer Kim Blanton invites you to follow us on Twitter @SquaredAwayBC. To stay current on our blog, please join our free email list. You’ll receive just one email each week – with links to the two new posts for that week – when you sign up here. This blog is supported by the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Comments are closed.

In addition to the systemic inequality derived from education and employment, the impact on Net Worth reinforces the same finding. In a recent analysis of Black Households, CFD highlights demographic, financial, and attitudinal differences of Black households in the US and the reinforcement of systemic disadvantages across many financial products and services.

Disparities are everywhere in healthcare as well. See my blog post:

https://www.whatswrongwithhealthcareinamerica.com/2020/07/sick-while-black-unhealthy-combination.html

There are multiple takeaways from that graph and not all of them are bad. If we compare the disparity in 2010 to 2020 (pre-COVID-19), you can see it shrinking continuously. I think this is a really positive trend and it may have continued that way if not for COVID-19.

Maybe in another 10 years, the unemployment rate for black people will have stabilised more so that it is not as easily affected by economic disasters.