The Trust Act Is Not the Way to Fix Social Security

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Social Security does need fixing, but Congress should debate and vote in full view.

Last month, I got an invitation to a forum on “Trust Fund Solutions,” which means Senator Mitt Romney (R-UT) is still pushing his TRUST Act. One of the bill’s co-sponsors – Senator Angus King (I-ME) – also appeared on the program. While the Trust Act sounds like a nice benign piece of bipartisan legislation, its unifying theme – namely, programs with trust funds – doesn’t make much sense, and the proposal could well lead to major cuts to Social Security.

The TRUST Act would create “Rescue Committees” for any federal government trust fund spending more than $20 billion annually that faces insolvency by 2035. Under these criteria, the TRUST Act would apply to Social Security’s Old Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) program, Medicare’s Hospital Insurance (HI) component, and the Highway Trust Fund. (Social Security’s separate Disability Insurance Trust Fund is scheduled to run out of money in 2057.)

Each Rescue Committee would consist of twelve current members of Congress, with three members chosen by the minority and majority leaders in the House and the Senate. The committee’s job would be to come up with legislative proposals to avoid trust fund depletion and assure the long-run solvency of each program. To be voted out by a Rescue Committee, the package would require not only a majority but also at least two members of each party.

Once voted out, Congress would have to consider the package without amendment and within a specified time period. Both chambers and the President would have to approve the legislation for the package to become law.

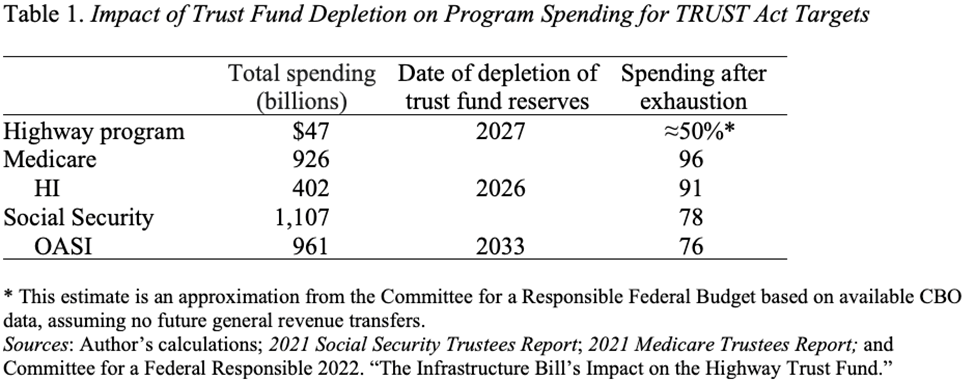

While Social Security, Medicare, and the Highway program do all have trust funds, the size of these trust funds and their impact on the programs differ dramatically (see Table 1). The Highway Trust Fund gets money from taxes on gasoline and other fuels to finance highway programs and mass transit. Traditionally, the program’s spending has exceeded these revenues, and Congress has filled the gap with general revenues, as they did recently through an infusion of funds from the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. The program definitely needs attention, but the depletion of the trust fund is nothing new.

In terms of Medicare, the Hospital Insurance (HI) Trust Fund receives payroll tax revenues and money from a surtax on higher-paid employees to cover inpatient hospital care and related services. It’s true that the trust fund’s reserves will be depleted in 2026, but even once this occurs Medicare will be able to pay 91percent of promised HI benefits and 96 percent of total benefits. Medicare raises a lot of complicated questions, such as how much to pay doctors and physicians and how to deal with new high-priced drugs, but the depletion of the trust fund is almost a non-issue.

For Social Security, the depletion of trust fund reserves is an important action-forcing event. Once the OASI trust fund reserves are depleted, revenues – primarily from the payroll tax – will be sufficient to cover only 76 percent of promised retirement benefits and 78 percent of total benefits.

It would indeed be wonderful if Congress enacted a plan to ensure the payment of full Social Security benefits for the next 75 years. Legislators have put forward a number of proposals that would both offer some enhancements and produce enough revenue to fill the financing hole. Congress should take up these proposals directly. No need to bundle Social Security with unrelated programs in order to create a complex and obscure decision-making process.

We don’t need “Rescue Committees.” Let’s have an open debate, then a vote, and see where we are.