This Is a Good Time to Rethink How Social Security Should Be Financed

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

The program’s “Missing Trust Fund” provides a strong case for an infusion of general revenues.

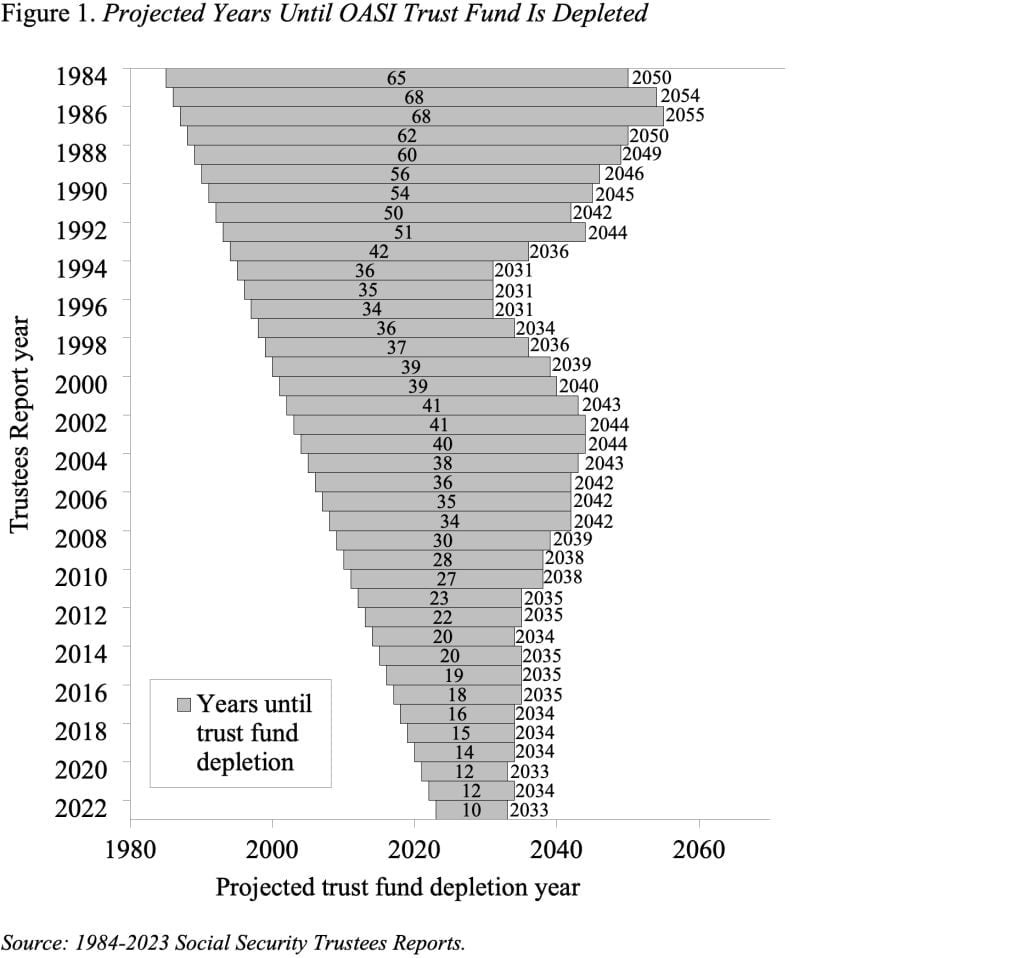

According to the latest Social Security Trustees Report, the program’s 75-year deficit increased to 3.61 percent of taxable payroll compared to 3.42 percent in 2022. The year for depletion of Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) trust fund assets moved up one year – from 2034 to 2033. Yes, the Disability Insurance (DI) trust fund has sufficient assets to pay benefits for the full 75-year period and the date of exhaustion for the combined OASDI trust funds is 2034. But combining the two systems would require a change in the law; hence, under current law, the relevant date is 2033 – a decade from now (see Figure 1).

The fact that in 2033 Social Security would be able to pay only 77 percent of scheduled benefits should focus our collective minds. Thinking of ways to restore balance to the program is not hard; the Social Security Actuaries publish an annual booklet with more than a hundred possible benefits cuts or revenue increases. Indeed, a lot can be said for maintaining a self-financed program where retirees receive benefits based on their contributions, and annual outlays are not subject to a congressional appropriations process. And if the cost of currently scheduled benefits simply exceeds what today’s workers are paying into the system, the traditional proposals to reduce benefits or raise payroll taxes would be most relevant.

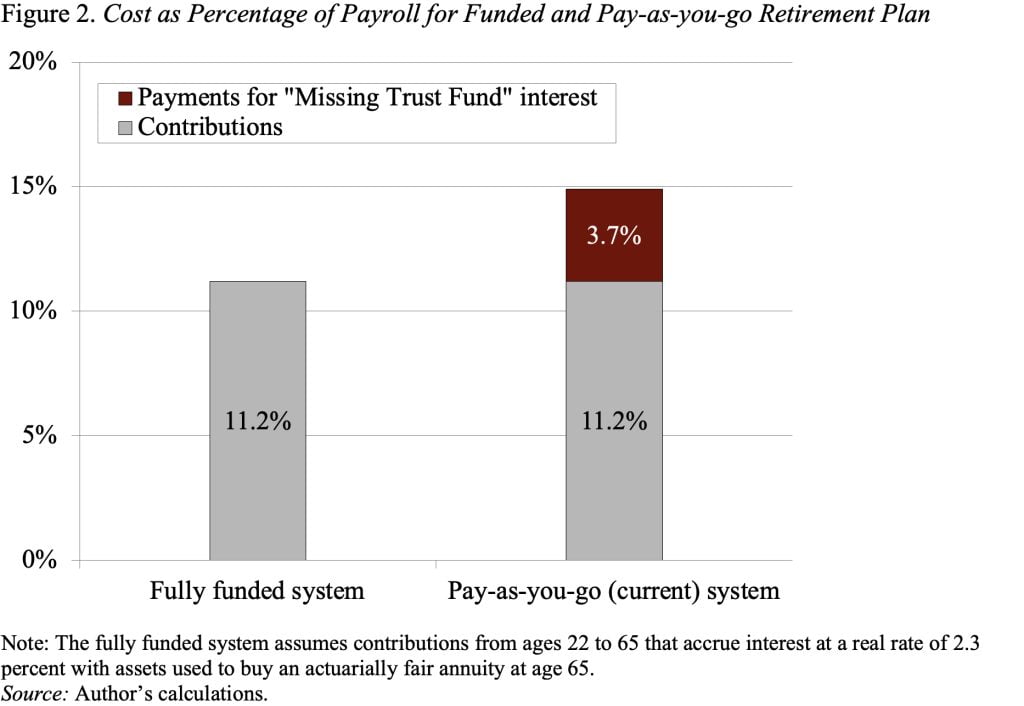

However, the cause of the shortfall lies elsewhere. Specifically, the program’s “pay-as-you-go” approach – with the exception of the recent build-up and spend-down of the current modest trust fund – makes the program look expensive. This financing approach is the result of a policy decision in the late 1930s to pay benefits far in excess of contributions for the early cohorts of workers. The decision essentially gave away the trust fund that would have accumulated and, importantly, gave away the interest on those contributions. The simplest way to see the implications of Social Security’s “Missing Trust Fund” is to consider the contribution rate required to finance the program’s retirement benefits under a funded retirement plan compared to a pay-as-you-go system (see Figure 2). Under a funded system, the combined employer-employee contribution rate for a typical worker would be 11.2 percent of earnings. Under our pay-as-you-go system, the total cost is 14.9 percent. The resulting difference of 3.7 percentage points (14.9 percent minus 11.2 percent) is due to the presence of a trust fund that can pay interest in a fully funded system but is missing in the pay-as-you-go system.

The impending depletion of trust fund assets is the ideal time to rethink the program’s financing structure and to consider whether a general revenue component might be appropriate. The rationale for general revenue funding is that Social Security costs are high, not because the program is particularly generous, but because the trust fund is missing. If policymakers choose to maintain Social Security benefits at current-law levels, little rationale exists for placing the entire burden of the Missing Trust Fund on today’s workers through higher payroll taxes; that component could be financed more equitably through the income tax.