Transferring Control of Finances: Timing Poses a Risk

The brief’s key findings are:

- As retirees grow older, many have to make major financial decisions while facing the risk of cognitive decline.

- One way to guard against missteps is to transfer control to a trusted agent, often a family member.

- A recent survey of investors ages 55+ found that:

- most have a dependable agent in mind;

- but they worry that they may delay transferring control; and

- that a delayed transfer could significantly hurt their finances.

- Thus, any measure to help the timely detection of cognitive decline could protect against costly mistakes.

Introduction

As older Americans approach the end of their lives, many have to make major financial decisions, including estate planning and long-term care arrangements. Unfortunately, with age comes the risk of cognitive decline, which may affect the quality of such decisions as well as making people easier targets for financial scams.

One way to help individuals protect their finances against mistakes is to involve a third party (an “agent”), commonly a family member, to take over financial decisions. But several conditions need to be met to make it work. First, the agent must be capable of making good decisions on behalf of the individual and be trustworthy. Second, the agent must be available when needed. Lastly, the transfer of control must be made at the right time, in particular before the aging individual makes irreversible mistakes.

This brief, which summarizes a recent study of the authors published by the American Economic Association, assesses the perceptions of individuals ages 55+ about the roles and limits of an agent in addressing cognitive decline, based on a sample of retail investors at the Vanguard Group.1Ameriks et al. (2023).

The discussion proceeds as follows. The first section provides background on the prevalence of cognitive decline and related financial mistakes; and it describes the survey and the sample. The remaining sections summarize the results of the survey. The second section reports that most respondents are confident that they have a suitable agent in mind. The third section explains, though, that respondents anticipate a significant chance that they might transfer control too late, primarily due to a failure to quickly detect their own cognitive decline. The fourth section summarizes the consequences of delay – respondents think it could substantially damage their finances and well-being. The last section concludes that any measure that can help the timely detection of cognitive decline could protect against serious financial mistakes, thereby improving late-life financial security.

Background

Cognitive decline is a significant risk for older Americans. About 23 percent of all individuals 65+ have a mild cognitive impairment; and an additional 11 percent have dementia. These rates, of course, grow as individuals age.2Manly et al. (2022).

Increasing evidence suggests that cognitive decline is related to financial mistakes.3For example, see Laibson et al. (2009) and Korniotis and Kumar (2011). When cognitive decline is unnoticed, the affected individual may continue making financial decisions, increasing the chance of suboptimal decisions and financial losses.4Mazzonna and Peracchi (2020). Cognitive decline also makes older individuals more vulnerable to financial exploitation and fraud.5For example, see Choi, Kulick, and Mayer (2008), Gamble et al. (2014), and DeLiema et al. (2020). Thus, people need a timely transfer of control over their finances to a trusted agent to mitigate the adverse impacts of cognitive decline.

To determine whether people are well situated, we conducted a survey of participants in the Vanguard Research Initiative (VRI), a panel of account holders at the Vanguard Group, Inc. The sample comprises individuals ages 55+ with at least $10,000 in their Vanguard accounts and internet access to complete online surveys. Comparisons with nationally representative samples of older individuals, such as the Health and Retirement Study, show that the VRI has good coverage of the above-median range of the U.S. net worth distribution. This survey on cognitive decline was conducted in July 2020 and included 2,489 respondents.

Do People Have a Capable Agent?

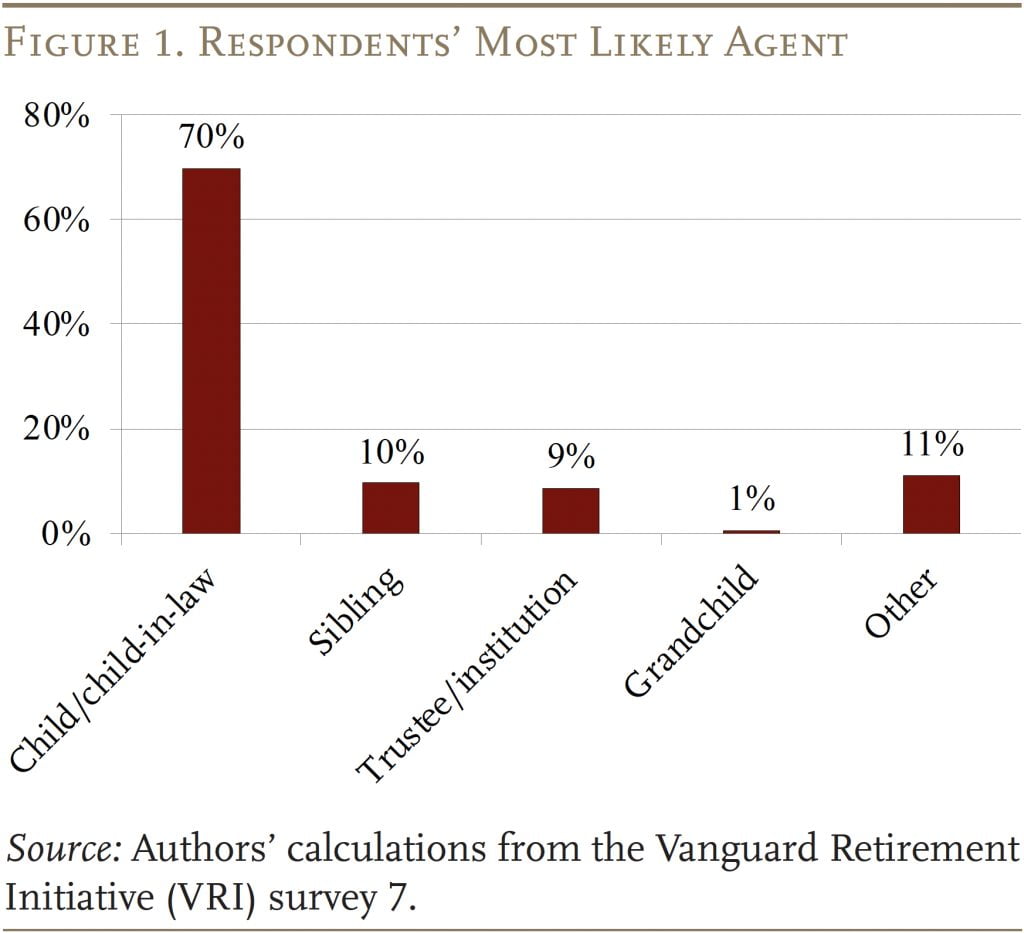

The survey begins by asking who will be the most likely person to make financial decisions on behalf of the respondent in case of severe cognitive decline (the “likely agent”). Respondents are asked to assume that they outlive a spouse or partner and, therefore, cannot have them as their agent. The vast majority of respondents (70 percent) report that the likely agent will be one of their children, while 10 percent say a sibling and another 9 percent select a trustee or institution (see Figure 1).

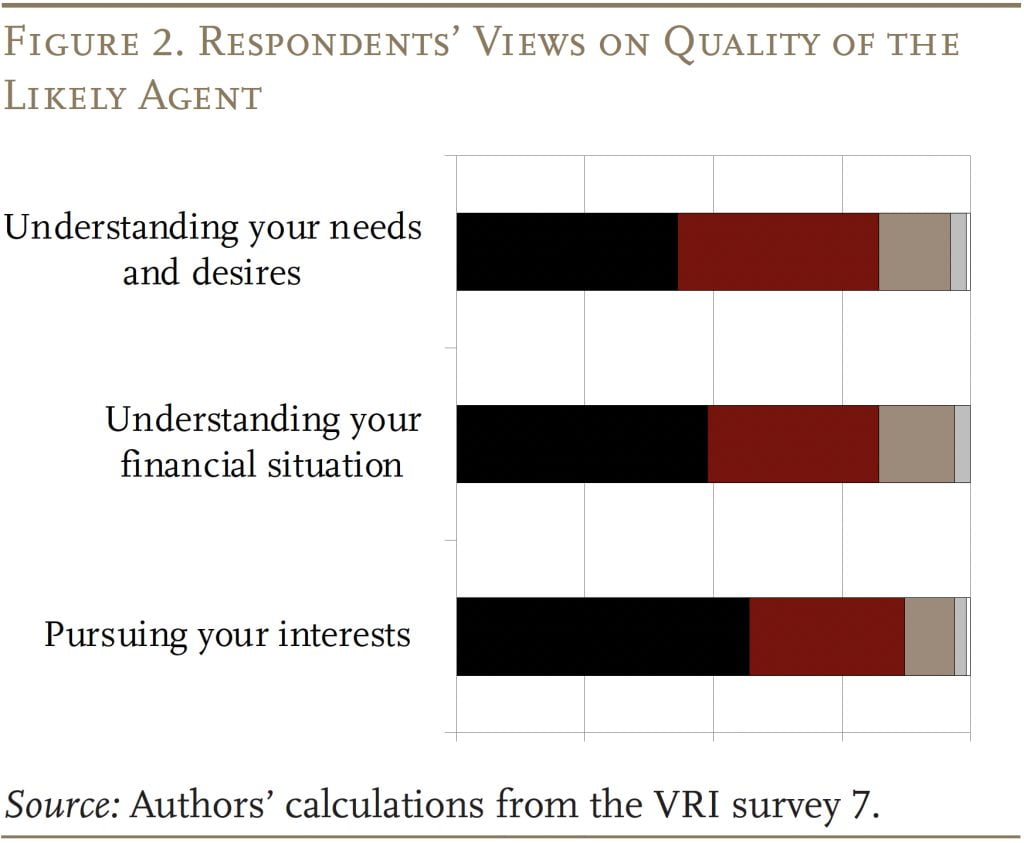

The respondents are overall very confident with the quality of their likely agent. The vast majority think the agent will be excellent or very good at understanding their needs and desires and their financial situation, and in pursuing the respondent’s interest (see Figure 2). The respondents are also very confident that the agent will be available to help when needed – they believe, on average, there is a 76-percent chance of this outcome.

Will the Transfer Be Timely?

The results so far reveal that the respondents have an agent in mind who is capable and available. Still, for an agent to capably protect a person’s finances from the effects of cognitive decline, the transfer of financial control should occur before people make irreversible mistakes. Many factors make it challenging to transfer control at the right time, including the elusiveness of cognitive decline.

The survey specifies a hypothetical situation to investigate the transfer timing issue. In this situation, the respondents are entering the last five years of their life and have mild cognitive decline. The progression of decline over their remaining years is left uncertain. The respondents must continue to decide how to handle their money if they are still in control and when to transfer control to the likely agent.

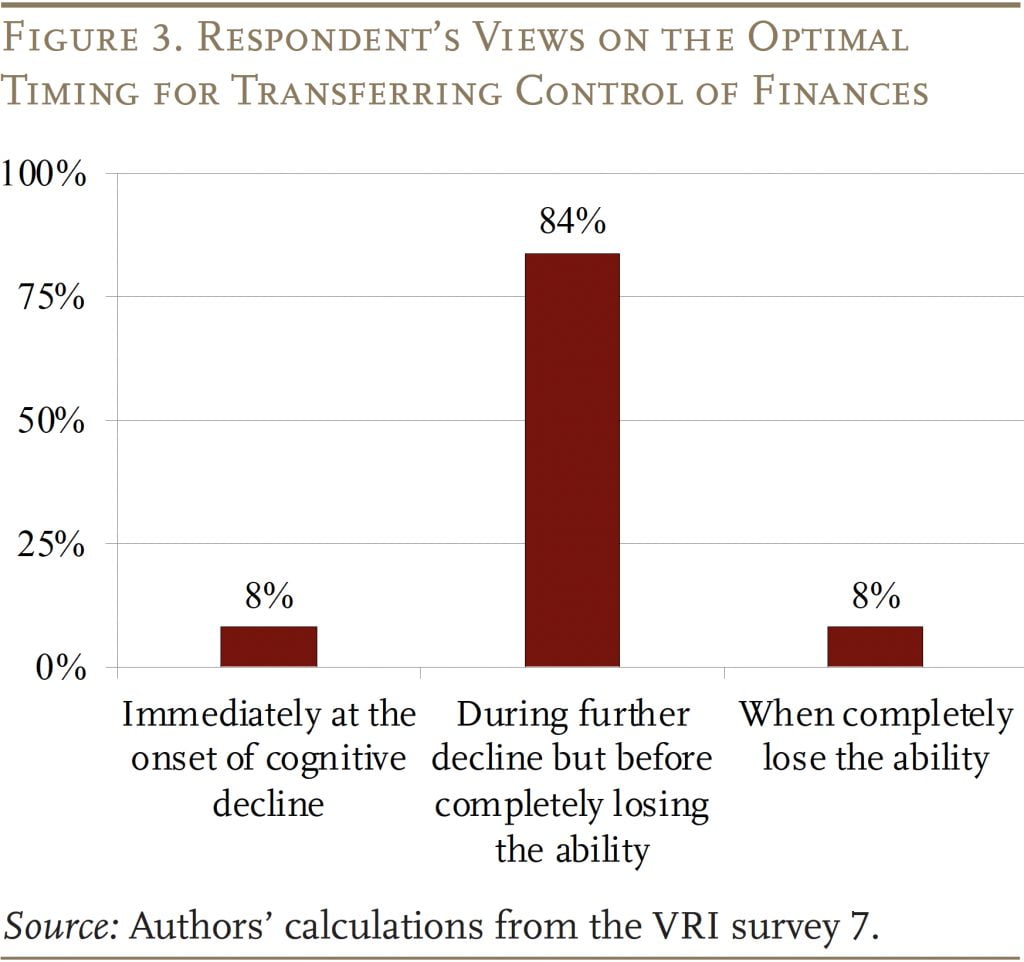

The survey then asks the optimal timing of the transfer of control. The respondents are asked to choose one of three options (see Figure 3). Very few respondents want to transfer control immediately at the onset of cognitive decline, even though it would reduce the chance of making financial mistakes, which suggests that the respondents value being their own agents when they feel they are still capable. Similarly, few opt for the other extreme of waiting until they completely lose the ability to manage their money. Instead, the vast majority – 84 percent – prefer a middle ground, where they risk some further decline but hope to avoid the worst.

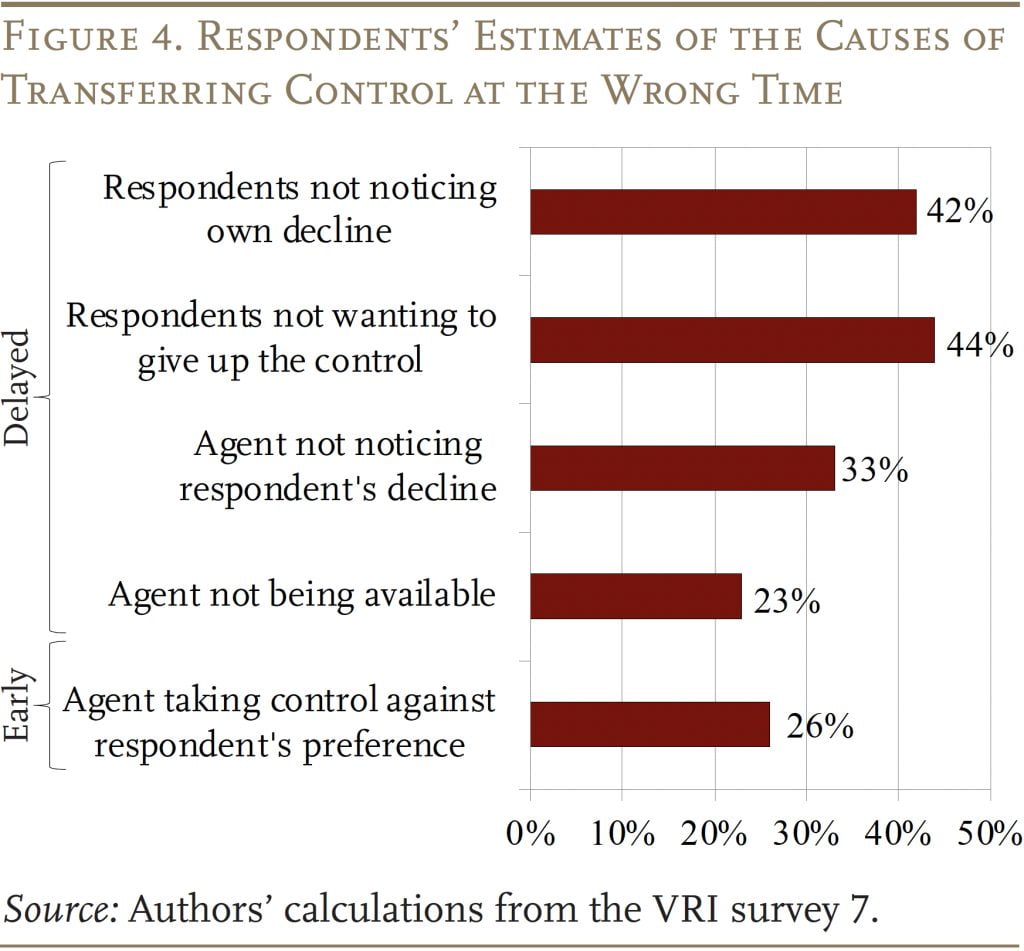

Strikingly, respondents think the chances of missing the optimal timing are significant. When asked about the subjective probability of having the transfer at the wrong time, the average respondent thinks there is a 35-percent chance of the transfer occurring too late and a 24-percent chance of it occurring too early. What could be the reasons for the transfer at the wrong time? Figure 4 shows that, regarding a delayed transfer, the respondents are concerned that they will not be able to notice their own decline – more than a 40-percent chance on average. They are also worried that, even though they currently believe that they should transfer control as cognitive decline progresses, they might change their mind and refuse to give up control (with the average subjective probability of 44 percent). On the flip side, as a cause for a premature transfer, the average respondent thinks some chance exists (26 percent) that the agent would take control too early against the respondents’ preferences.

How Harmful is Bad Timing?

To measure the expected welfare cost of making a transfer at the wrong time, the survey asks the respondents to consider two scenarios:

- Scenario 1: The transfer happens at the optimal timing.

- Scenario 2: The transfer happens at the wrong time (either too late or too early, depending on which one the respondent is more concerned about).

The respondents are obviously better off in Scenario 1. Then the survey asks what level of additional wealth under Scenario 2 would make them feel just as well off as in Scenario 1. If the respondents believe that transferring control at the wrong time would have more negative impacts, they would demand more wealth under Scenario 2 to compensate.

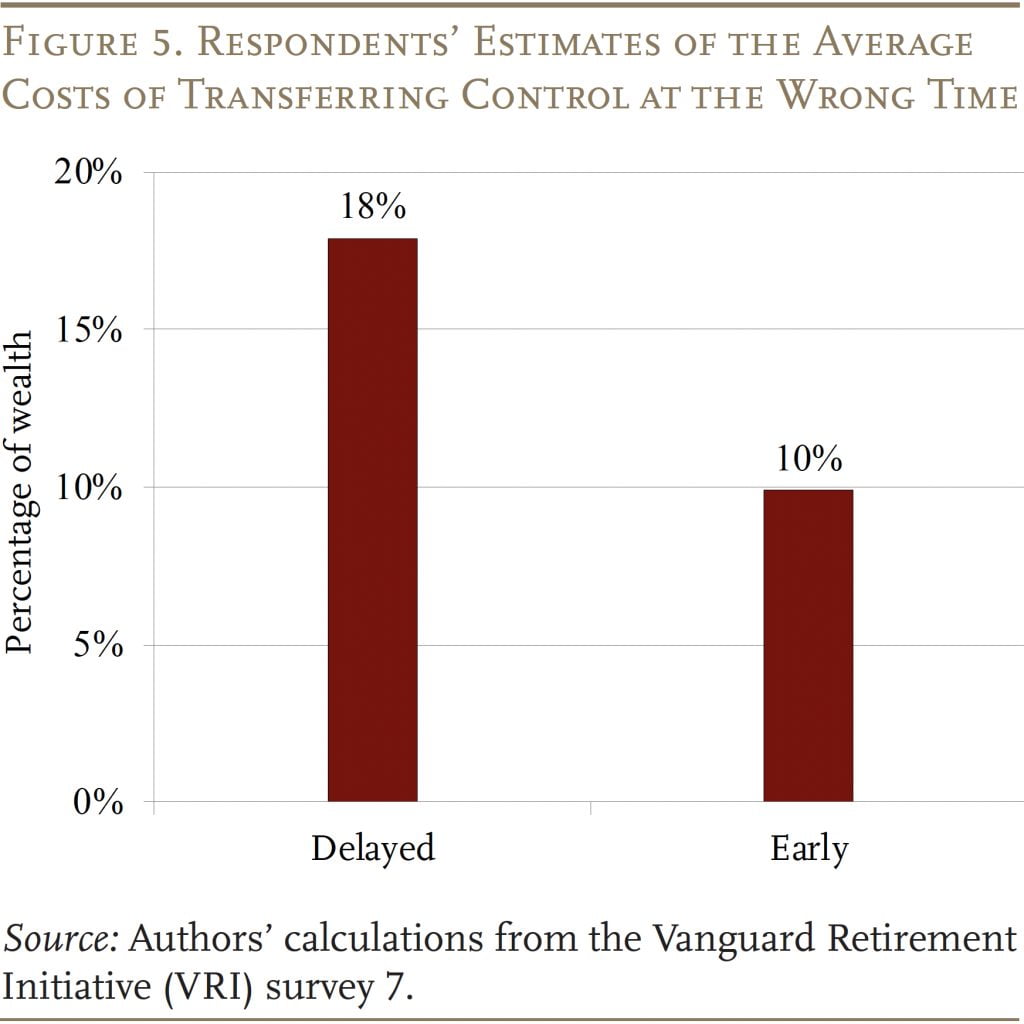

The respondents believe that a transfer at the wrong time is likely to be very costly. For a delayed transfer, the average respondent believes the damage would equal 18 percent of their wealth (see Figure 5). The average cost of a transfer that is too early is smaller, but still significant at 10 percent.

Conclusion

Older individuals with some retirement assets think they have a dependable agent they can rely on when they experience cognitive decline. Still, they perceive a significant chance of missing the optimal timing to transfer control over finances to the agent. Having a significantly delayed transfer compared to the optimal timing is particularly concerning. The survey respondents’ desire to keep control while still capable exposes them to the risk of a delayed transfer. A delayed transfer may happen for many reasons, including the elusiveness of cognitive decline. If a delay were to occur, the survey respondents expect it to cause significant damage to their financial well-being. These results suggest that any measures that can help secure the optimal timing of the transfer of control – e.g., regular monitoring of cognitive abilities – can go a long way to protecting older Americans’ financial well-being.

References

Ameriks, John, Andrew Caplin, Minjoon Lee, Matthew D. Shapiro, and Christopher Tonetti. 2023. “Cognitive Decline, Limited Awareness, Imperfect Agency, and Financial Well-being.” American Economic Review: Insights 5: 125-140.

Choi, Namkee G., Deborah B. Kulick, and James Mayer. 2008. “Financial Exploitation of Elders: Analysis of Risk Factors Based on County Adult Protective Services Data.” Journal of Elder Abuse and Neglect 10: 39-62.

DeLiema, Marguerite, Martha Deevy, Annamaria Lusardi, and Olivia S. Mitchell. 2020. “Financial Fraud among Older Americans: Evidence and Implications.” Journal of Gerontology: Series B 75: 861-868.

Gamble, Keith Jacks, Patricia A. Boyle, Lei Yu, and David A. Bennett. 2014. “The Causes and Consequences of Financial Fraud Among Older Americans.” Working Paper 2014-13. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Korniotis, George M. and Alok Kumar. 2011. “Do Older Investors Make Better Investment Decisions?” Review of Economics and Statistics 93: 244-265.

Laibson, David, Sumit Agarwal, Xavier Gabaix, and John C. Driscoll. 2009. “The Age of Reason: Decisions over the Life Cycle and Implications for Regulation.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 39: 51-117.

Manly, Jennifer, Richard Jones, Kenneth M. Langa, Lindsay H. Ryan, Deborah A. Levin, Ryan McCammon, Steven G. Heeringa, and David Weir. 2022. “Estimating the Prevalence of Dementia and Mild Cognitive Impairment in the US.” Journal of the American Medical Association 79(12): 1242-1249.

Mazzonna, Fabrizio and Franco Peracchi. 2020. “Are Older People Aware of Their Cognitive Decline? Misperception and Financial Decision Making.” IZA Discussion Paper 13725. Bonn, Germany: Institute of Labor Economics.

University of Michigan. Health and Retirement Study, 2022. Ann Arbor, MI.

Endnotes

- 1Ameriks et al. (2023).

- 2Manly et al. (2022).

- 3For example, see Laibson et al. (2009) and Korniotis and Kumar (2011).

- 4Mazzonna and Peracchi (2020).

- 5For example, see Choi, Kulick, and Mayer (2008), Gamble et al. (2014), and DeLiema et al. (2020).