Washington State Establishes a Long-Term Care Program

The brief’s key findings are:

- Long-term care is the major uninsured risk most retirees face. To mitigate this risk, Washington State enacted WA Cares in 2019.

- WA Cares covers up to $36,000 for care needs and is financed by a 0.58-percent payroll tax.

- The state proactively identified and resolved potential kinks in the program, and its finances appear solid over the long term.

- WA Cares will offer valuable support for middle-income households and serve as a proof of concept for other states and the federal government.

- The one risk it faces is a ballot initiative that would make it voluntary, which would essentially kill the program.

Introduction

Long-term care is the major uninsured expense for most retirees. Neither private health insurance nor Medicare covers long-term care expenses, although Medicare provides for care in a skilled nursing facility for up to 100 days following hospitalization. Long-term care insurance is available in the private market, but less than 5 percent of people purchase plans.1 As a result, many turn to family members for care or are forced to deplete their resources to qualify for Medicaid.

To mitigate some of this risk, the state of Washington in 2019 enacted WA Cares – a state-level program to provide qualifying Washington residents with a lifetime benefit of up to $36,500 (adjusted for inflation) to cover long-term care costs, financed by a payroll tax of 0.58 percent. In its first year, the program has accumulated more than $1 billion in reserves. The first benefits will be paid in July 2026. While this initiative is modest, it will provide valuable support for middle-income households and serve as an important proof of concept for other states and for the federal government should Congress decide to establish a national social insurance program for long-term care.

The discussion proceeds as follows. The first section discusses the long-term care landscape, and the second reviews the nation’s failed attempt to create long-term care insurance through the CLASS program. The third section describes the evolution of WA Cares as the state identified and addressed kinks in the program over the last five years. The fourth section looks at the long-term outlook for the program’s finances, and discusses the threat of a ballot initiative to make participation voluntary. The final section concludes that WA Cares will provide not only valuable support to the state’s middle-class families, but also a wealth of information on using social insurance to address some of the risks of long-term care costs.

The Long-term Care Landscape

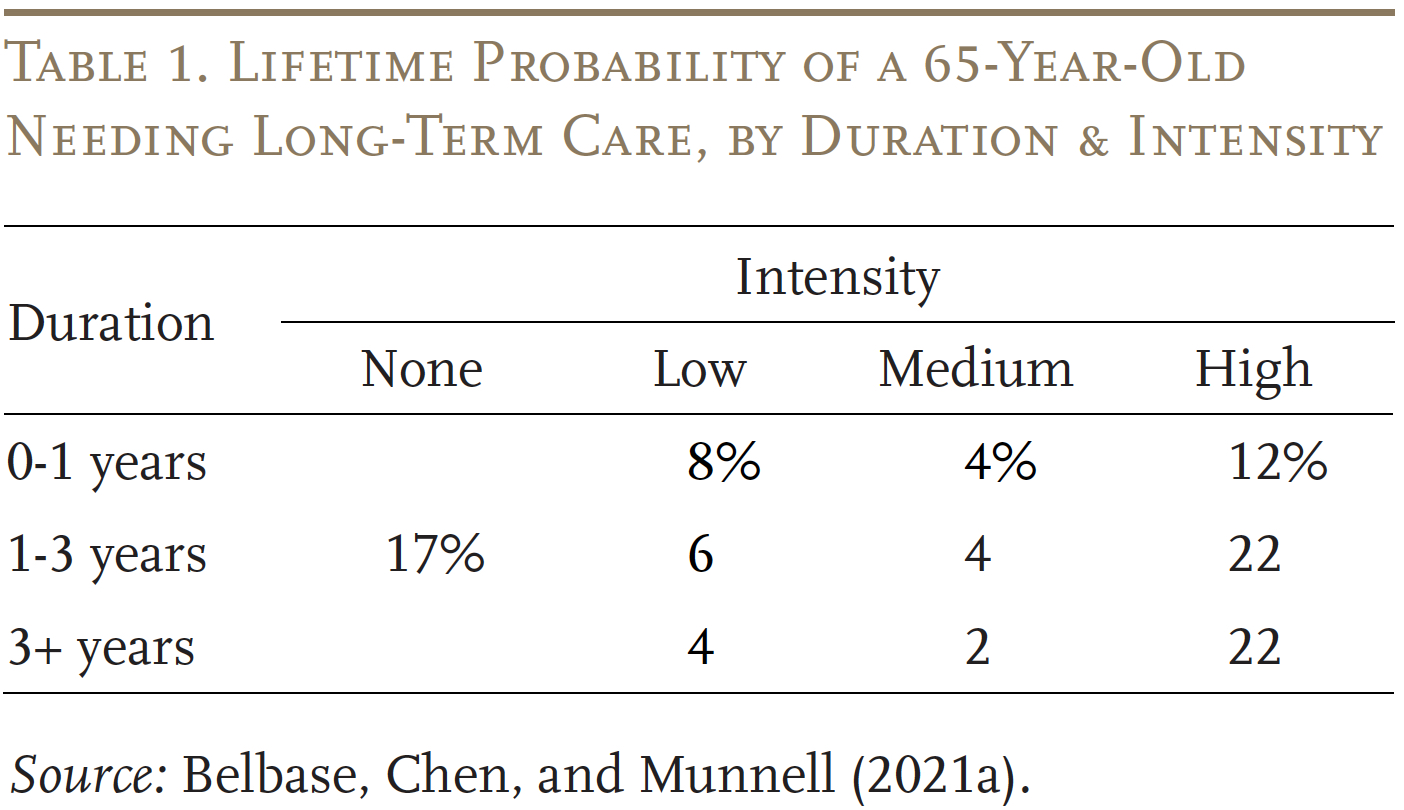

Most older adults will need some long-term care. In fact, projections for the care needs of the average 65-year-old over their retirement show that only 17 percent will get by scot-free (see Table 1). However, among those who will need care, the intensity and duration vary dramatically. About 22 percent will need high-intensity care for more than three years – the most dreaded outcome – with the remaining falling somewhere between the two extremes.

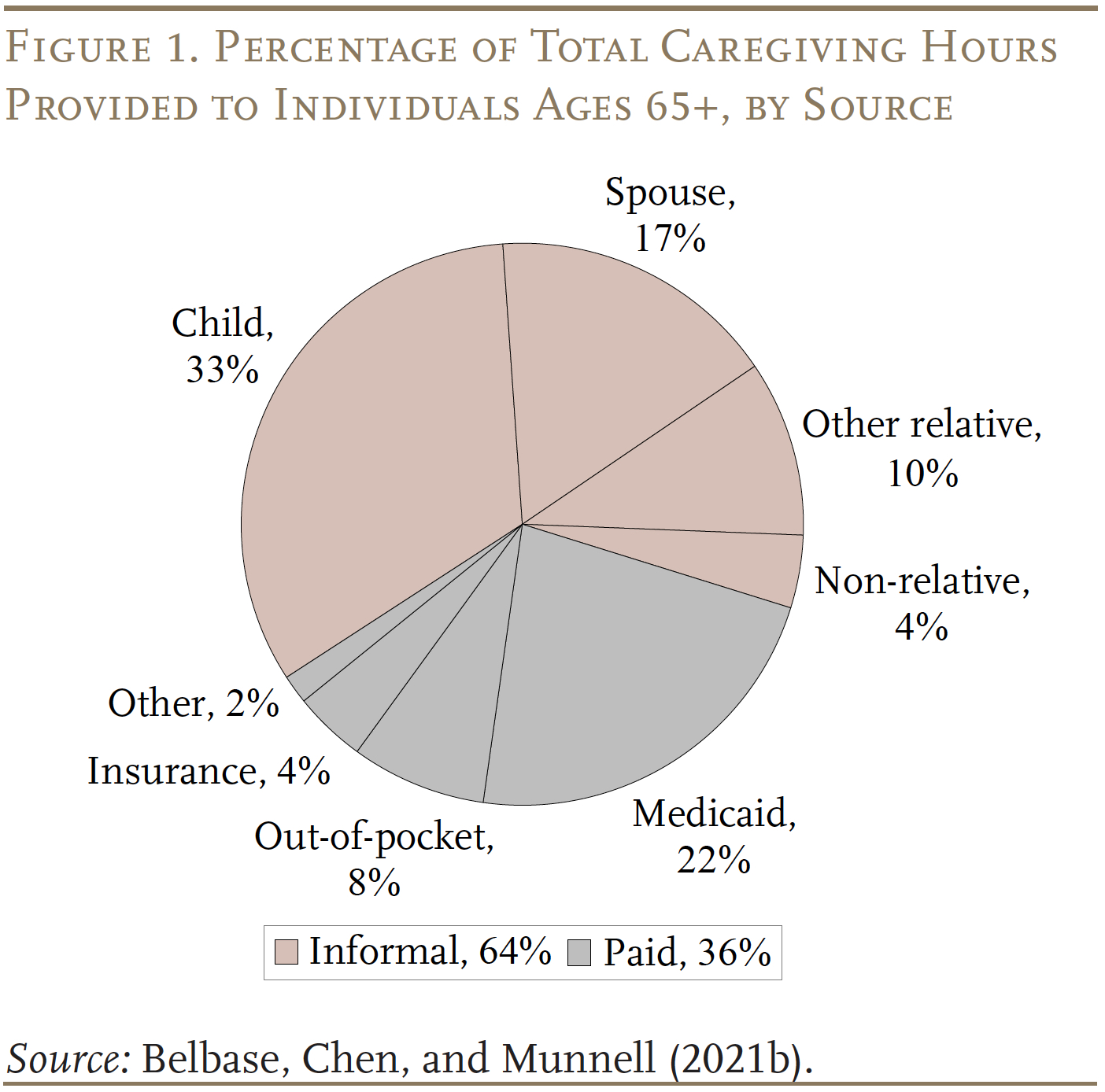

Households cover these long-term care needs in two ways. The more common is unpaid informal care provided by family members (see Figure 1). The less

common way is paid formal care, financed primarily out-of-pocket or through Medicaid. Currently, as noted, less than 5 percent of adults has long-term care

insurance.

Paid formal care is really expensive. The average cost of a home health aide was $33/hour in 2023.2 Paid care as a supplement to informal care for someone with high-intensity needs would cost more than $35,000 a year – more than the total annual income for about half of older Americans and more than the total net worth for about one-fifth.3 Assisted living facilities and nursing homes are even more expensive, costing around $64,000 and $117,000 a year, respectively.4 Going forward, paid care is likely to be unattainable for a large share of households.

Medicaid has become a default payor for catastrophic costs. However, the income limit in 2024 for Medicaid eligibility for those over age 65 is typically around $2,800 ($5,600 for couples) and the asset limit is typically $2,000 ($3,000 for couples), but varies by state. So, qualifying for Medicaid requires middle-income people to spend down the household’s resources.5

In terms of unpaid informal care, social change will likely reduce its availability going forward.6 Declines in fertility and the rise in divorce will diminish the supply of informal caregivers.7 And, the share of retirees with extended family or other community support systems has been declining for three decades.8 One study estimated that about one-fifth of retirees are “elder orphans.”9 A reduction in informal care increases the need for expensive formal care, which will be out of reach for many. The end result will be that many will have care needs that simply go unmet.

In short, the current system for long-term care places an enormous burden on relatives caring for loved ones, forces families to impoverish themselves, or leaves people without the care they need.

Lessons from Earlier Efforts – CLASS

WA Cares is not the first government attempt to provide long-term care insurance. The 2010 Affordable Care Act included a provision to establish a program known as Community Living Assistance Services and Supports, or CLASS. CLASS, unlike WA Cares, was designed as a voluntary program.

To be covered by the CLASS program, a worker’s employer had to elect to participate, in which case workers would be automatically enrolled in the program and have their premiums deducted directly from their paychecks, unless they decided to opt out. CLASS differed from private long-term care insurance in that eligibility depended only on minimal employment requirements and involved no underwriting to disqualify those with health problems. The premium was to be set at a level that ensured the program would be self-financing over a 75-year period. Participants would have been eligible for benefits after paying premiums for five years and the Congressional Budget Office assumed an average daily benefit of $75 that would increase each year with inflation. (The law specified that the average minimum benefit must be at least $50.) The benefits, provided through a debit card account, would have continued for as long as the individual needed care.10

The key problem with CLASS was that success depended on broad participation from American workers, especially the young and healthy. This objective required that employers decide to offer the plan and that individuals – automatically enrolled – did not opt out. Broad participation is an unrealistic goal given people’s natural reluctance to think about the possibility of becoming disabled and the backstop of Medicaid. As a result, without underwriting to exclude those with health problems, a greater proportion of the less healthy would have been attracted to the program (adverse selection). Disproportionate participation by those with health problems would have driven up per-participant costs and, given the requirement of 75-year actuarial balance, required an increase in premiums. Premium increases would have further discouraged healthy people from signing up and encouraged healthy participants in the program to drop their coverage as their perception of value declined. Such continued shifts in the composition of the covered population would eventually have necessitated even steeper premium hikes, creating a “death spiral.”11

In response to the risks associated with adverse selection, CLASS was never implemented and was repealed by Congress in early 2013. Nevertheless, the enactment of the legislation acknowledged the problems with the current system, and the repeal of the legislation acknowledged the infeasibility of a voluntary approach.12

Development of WA Cares

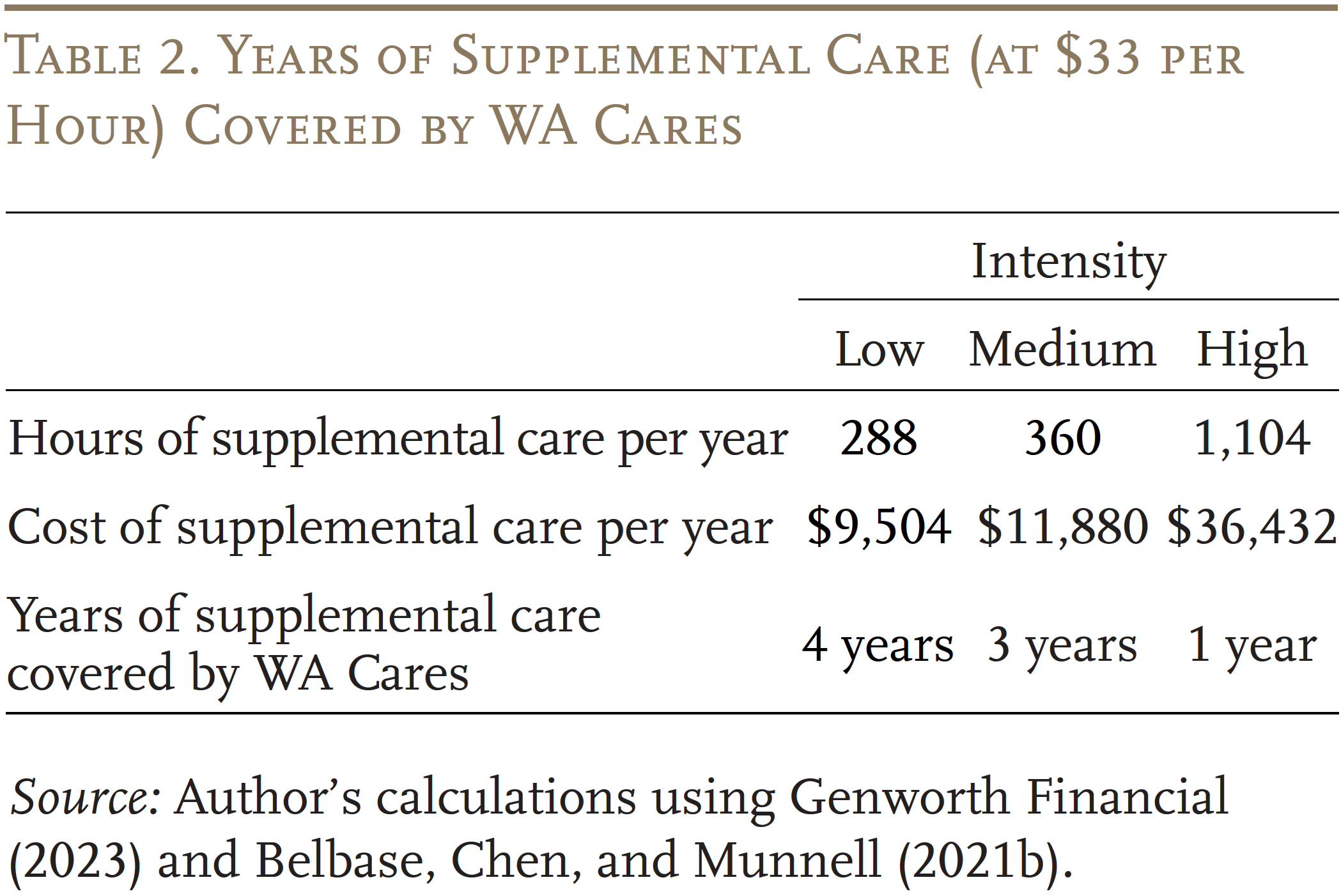

To meet the gap in long-term care insurance, in 2019 the state of Washington enacted WA Cares to provide qualifying residents with up to $36,500 (adjusted for inflation) to cover the cost of long-term care services or supports.13 While the program is clearly not designed to meet all long-term care needs, it would cover several years of paid care as a supplement to informal care (see Table 2). The program is financed by a 0.58-percent tax on total earnings – that is, including earnings above Social Security’s taxable maximum.

The original plan was to start collecting taxes in January 2022 and to pay first benefits in January 2025, but the schedule was postponed. Under the revised schedule, the collection of payroll taxes began in July 2023, and the first benefits will be paid in July 2026. The delay allowed the state to improve the fairness of the program. For example, it created a pro-rated benefit for near-retirees (those born before 1968), who might not have been able to satisfy the 10-year vesting pathway. Most importantly, it made benefits portable, so that workers who leave the state can continue participating and claim benefits elsewhere, or even abroad.

The delay also allowed the state to iron out some kinks in the program, regarding individuals unlikely to ever collect, the ability to opt out with private insurance, and the treatment of the self-employed. It is worth saying a word about each since they are thorny issues that would arise in any state program.14

Individuals Not Likely to Collect Benefits

After enactment, the administrators recognized that the program would levy taxes on some individuals who were unlikely ever to receive benefits. These groups included workers who lived in another state, workers resident under non-immigrant visas, military spouses who were likely to leave the state, and veterans with at least 70 percent disability who already qualify for VA benefits. To correct this problem, the legislature passed amendments allowing members of these four groups to apply for exemptions from the payroll tax.15 Allowing these groups to participate on a voluntary basis creates the possibility of some adverse selection, whereby the healthy and wealthy are less likely to sign up. However, these groups are relatively small, in total accounting for less than 2 percent of the state’s workforce.16

Opting Out with Private Insurance

Individuals who attested before December 31, 2022, that they had private long-term care insurance with benefits comparable to the state plan before November 1, 2021, would be exempt from paying the tax and barred from the program. Critics were alarmed that 443,649 exemption requests were filed with the state as of early December 2021.17 Indeed, given that the requested exemptions amounted to about 13 percent of the 3.5 million Washington residents employed in 2022 and that less than 5 percent of adults nationwide had long-term care insurance, the numbers were suspiciously high.18 The Washington legislature recognized the possible adverse selection problem and instructed the LTSS Trust Commission, which oversees WA Cares, to explore ways to require recertification (to ensure that people were not buying policies to get an exemption and then dropping them), but no such process was implemented. On the positive side, the number of requested exemptions dropped sharply to 32,638 in 2022, and no claims can be filed after 2022. So, the private insurance exemption was a one-shot problem and its impact will diminish over time, but other states adopting such a long-term care program could include a rigorous certification procedure to verify private coverage rather than allowing people to self-attest.

The Self-Employed

The self-employed were only included in the program if they opted in because the state of Washington, without an income tax, has no automatic mechanism for collecting taxes from this group. Since the payroll tax is levied on uncapped earnings, the self-employed with high earnings were less likely to join. In addition, the self-employed were in a position to game the system. They could opt in only for the last 10 years of their career, or opt in for 10 years early in their career and then opt out as soon as they hit the 10-year vesting threshold, then opt back in when they needed benefits.

To prevent such gaming of the system, the legislature ruled in 2021 that the self-employed who wish to participate in the program had to opt in within three years of when premium collection began. Once they opt in, they remain enrolled and subject to tax on self-employment income until they file a notice that they are no longer self-employed or have retired.19

Ideally, the employed and the self-employed should be treated similarly under a long-term care insurance program. Such an outcome would be easy to administer in any state with a personal income tax. For states without an income tax, the state could seek cooperation from the Internal Revenue Service in verifiying total W-2 and Schedule C income of everyone who participates in the program and base the payroll tax on the sum.

Finances of WA Cares

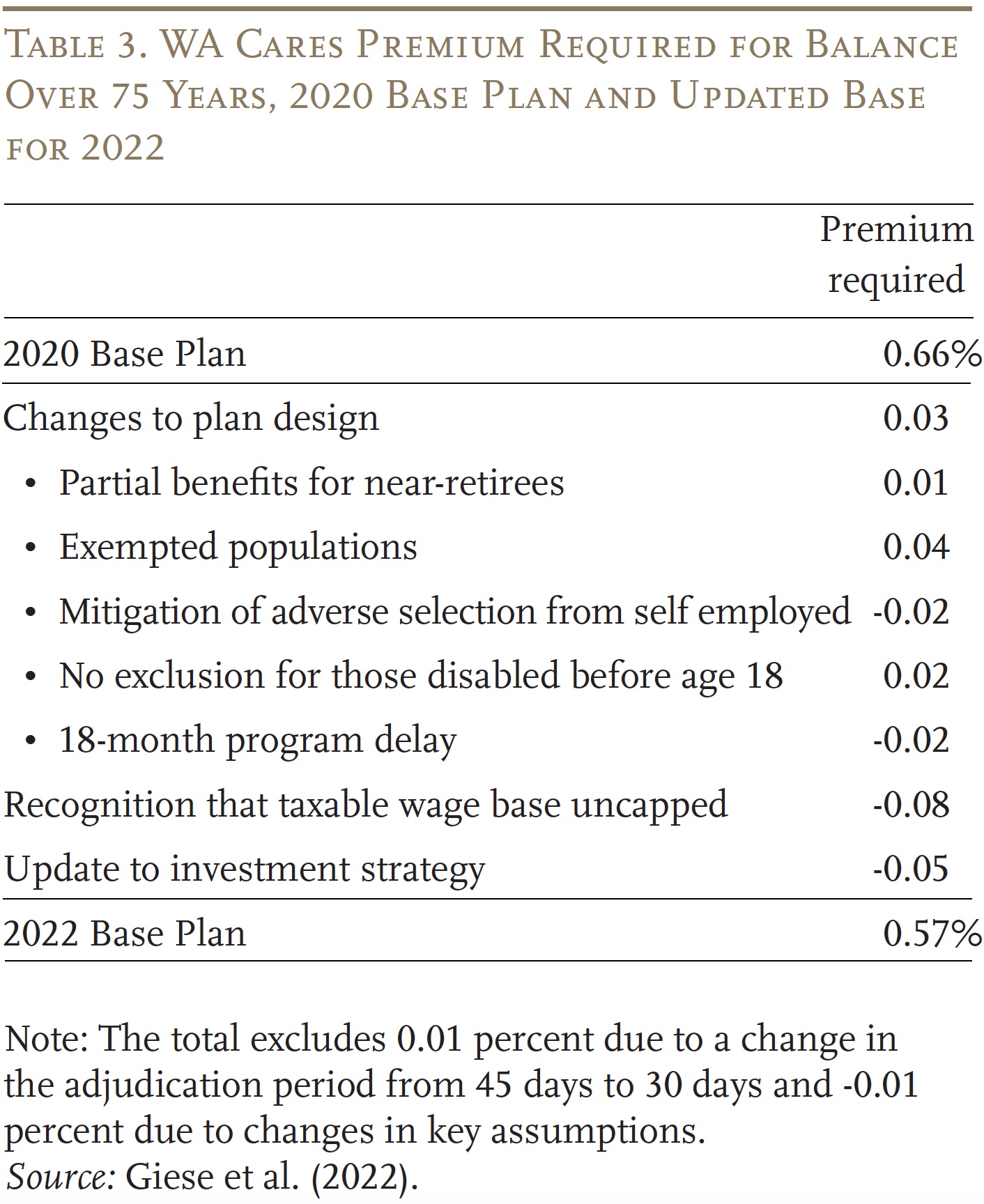

In 2020, the state commissioned an actuarial assessment of the WA Cares projected costs and outlays over a 75-year period. The most recent assessment, which reflected updated information about the program, was released in October 2022.20 The changes from 2020 to 2022 are interesting because they highlight the issues discussed above, which means that the actuaries have noted benefit expansions when they have occurred and recognized the costs of adverse selection where they exist. Before looking at the reasons for the changes, it is important to note that the required premium contribution to keep the program solvent for 75 years is 0.57 percent – very close to the legislated rate of 0.58 percent.21 Moreover, this assessment ignores the savings to the state Medicaid program, which Milliman estimates will amount to about 10 percent of program costs.22

Plan design changes between 2020 and 2022 increased program costs by 0.03 percent of wages (see Table 3). Leading the list is providing pro-rated benefits for near-retirees and exempting populations unlikely to receive benefits from mandatory coverage, which increases the likelihood that high-earning, healthy individuals will not participate. Offsetting those increases is the mitigation of adverse selection of the self-employed. Dropping the exclusion of those disabled before age 18 increased cost, but these costs were offset by the 18-month program delay. The increase in cost due to program changes was more than offset by the clarification that the payroll tax applied to uncapped wages – that is, including earnings in excess of the Social Security taxable wage base –and the expansion of investment options beyond U.S. Treasuries.

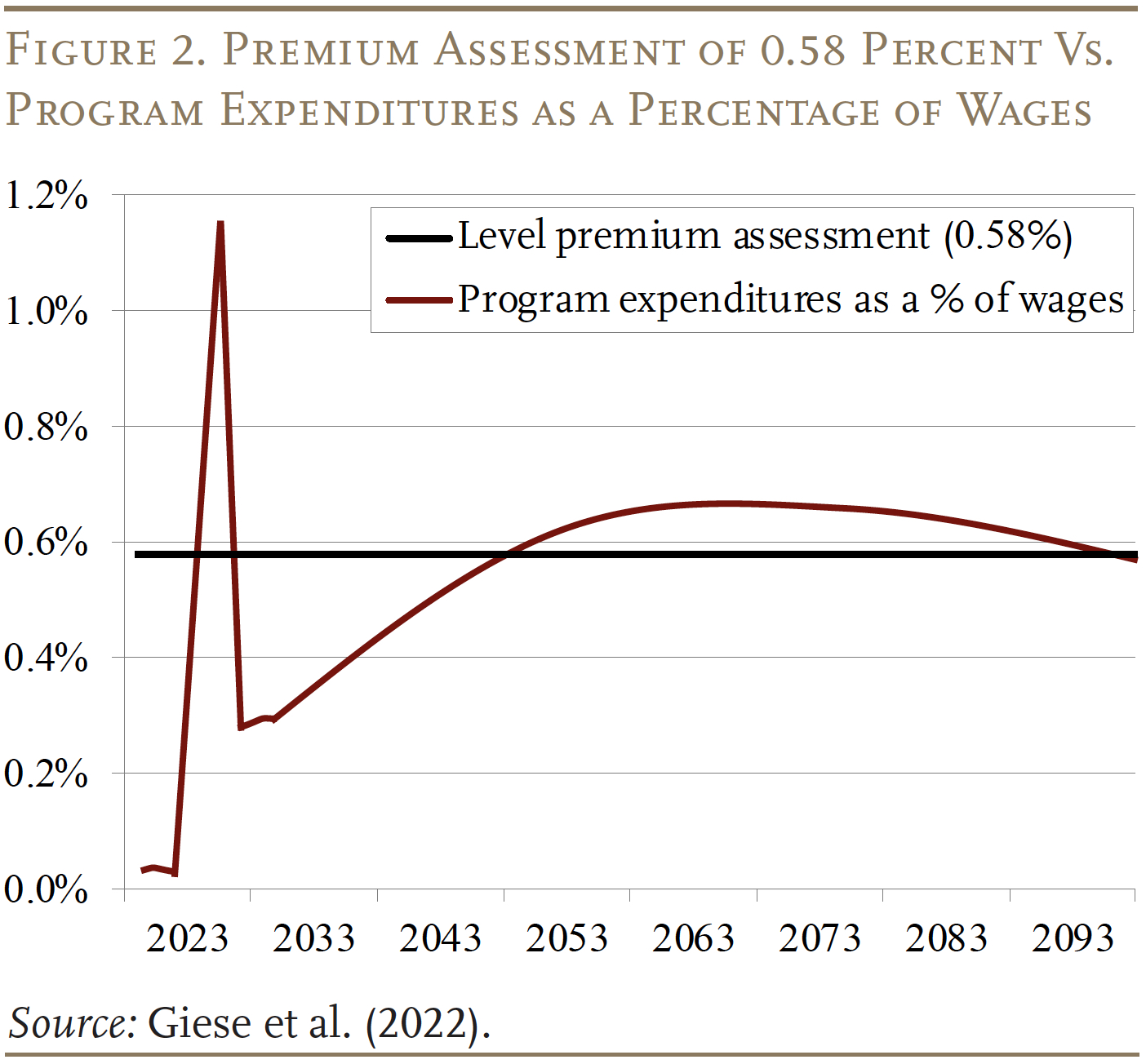

The fact that a tax rate of 0.58 percent covers all costs over a 75-year period does not tell the whole story. If the pattern involved surpluses in the early stages and deficits later, 75-year deficits would appear as soon as the projection period moved out a year – as has occurred with the Social Security program. Fortunately, the relationship between revenues and expenditures is relatively stable at the end of the period (see Figure 2).

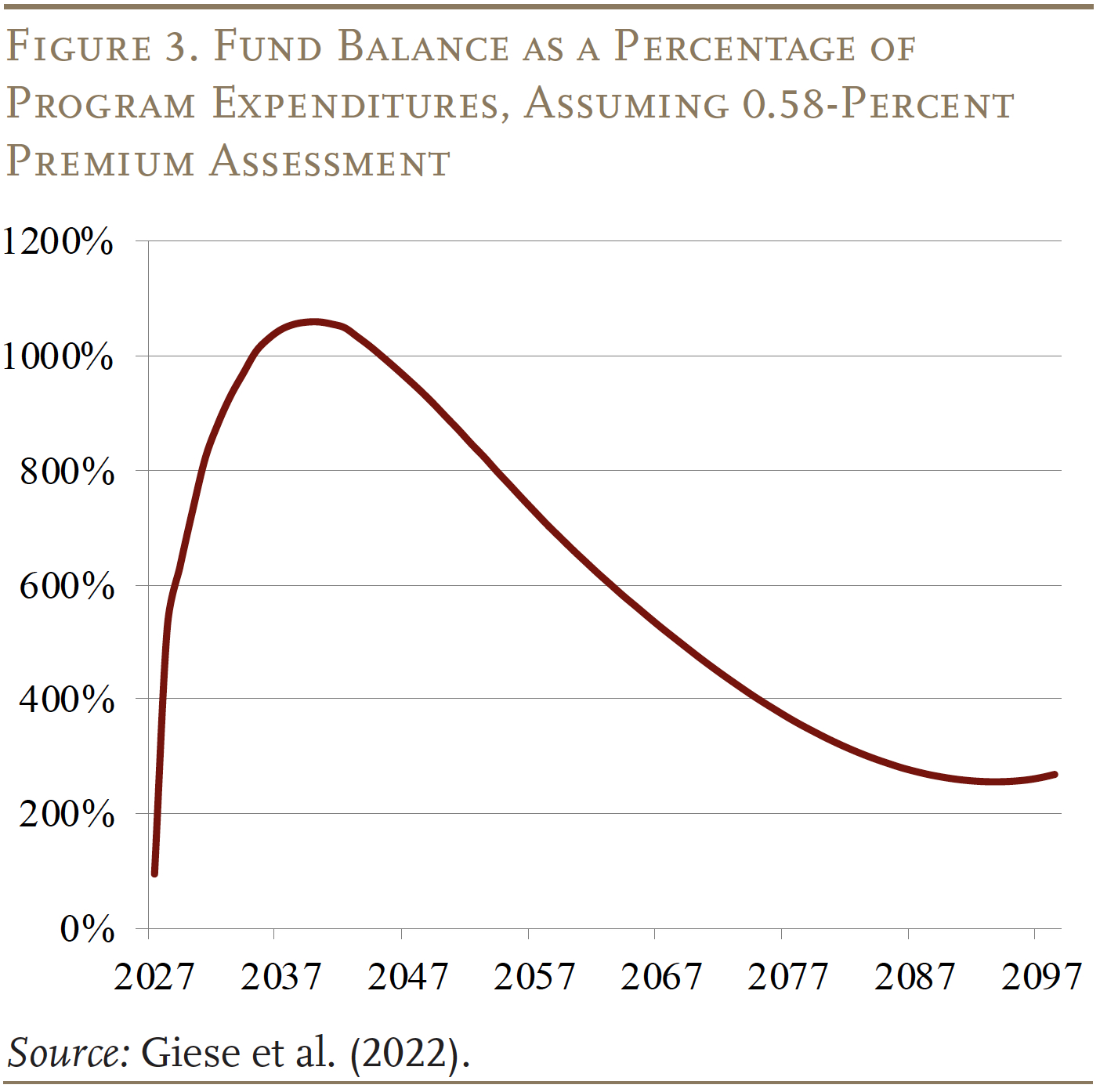

The pattern of expenditures and revenues is reflected in the fund balances as a percentage of outlays (see Figure 3). Fund balances rise sharply in the early years – when premiums are flowing in and most participants have not yet satisfied the vesting requirements – and then decline when expenditures exceed revenues. By the end of the period, the fund balance is projected to stabilize around 270 percent of expenditures. Thereafter, the fund balance may well grow, as benefit payments, which are indexed to prices, rise more slowly than revenues, which are based on wages.

The financial projections merit several comments. First, it is important to reiterate that the actuaries clearly incorporate the impact of adverse selection in their projections. Second, the 2022 projections do not include the impact of making benefits portable, but this omission should not be significant given that the legislature included cost offsets when it enacted the provision.23 Third, some discussion has occurred about investing a portion of the fund assets in equities, which would likely increase the revenue projections.24 Finally, since all projections are uncertain, it would make sense to include some automatic adjustment mechanism to change benefits or taxes should 75-year imbalances emerge.

While the program seems solidly funded, a threat has emerged in the form of a November 2024 ballot initiative to make participation voluntary.25 As evident from the demise of CLASS, a program financed with voluntary contributions will almost certainly go into a death spiral.

Conclusion

The likelihood of needing a meaningful amount of long-term care is the major risk facing older individuals. The median private nursing home room cost of nearly $120,000 per year exceeds the annual income of over 90 percent of the elderly, and the supply of home healthcare workers is very tight. Medicaid provides support for those with very limited assets and income, and a few people – less than 5 percent – buy long-term care insurance, but the vast majority of older Americans face the risk of large outlays on care as they age.

Recognizing the need for collective action, the state of Washington in 2019 enacted WA Cares – to provide qualifying residents up to $36,500 (adjusted for inflation) so that they can remain in their homes or to pay for short institutional stays. The program will be particularly valuable to the state’s middle-class families. Moreover, recognizing that the program does not meet all needs, the Commission has worked with private insurers and consumer protection advocates to design a statutory framework for a supplemental private LTC policy, which would insure risks above $36,500 and allow continuity of care, particularly by family caregivers. This optional product would be available for those wishing to augment the base benefit provided by WA Cares.

At this point, Washington’s long-term care program is in operation. In its first year, the program has accumulated more than $1 billion in reserves. The first benefits will be paid in July 2026. Its finances appear to be solid over the next 75-year projection period. Other states are interested in a similar initiative. New York, Massachusetts, and California have all authorized funding for actuarial feasibility studies; California has completed its studies. Additional states are in earlier stages of exploration. The major risk to WA Cares is the 2024 ballot initiative to make participation voluntary, in which case the program would no longer be feasible.

References

Aaron, Henry J. 2022. “The Future of WA Cares: A Response to Warshawsky.” Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

American Academy of Actuaries. 2011. “Actuaries Agree with HHS Concerns on CLASS Program.” News Release (October 14). Washington, DC.

American Academy of Actuaries. 2009. “Actuarial Issues and Policy Implications of a Federal Long-Term Care Insurance Program.” Letter to the U.S. Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions. (July 22). Washington, DC.

Ballotpedia. 2024. “Washington Initiative 2124, Opt-Out of Long-Term Services Insurance Program Initiative.” Middleton, WI.

Belbase, Anek, Anqi Chen, and Alicia H Munnell. 2021a. “What Level of Long-Term Services and Supports Do Retirees Need?” Issue in Brief 21-10. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Belbase, Anek, Anqi Chen, and Alicia H Munnell. 2021b. “What Resources Do Retirees Have for Long-Term Services & Supports?” Issue in Brief 21-16. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Brown, Susan L. and I-Fen Lin. 2012. “The Gray Divorce Revolution: Rising Divorce Among Middle-Aged and Older Adults, 1990-2010.” Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences & Social Sciences 67(6): 731-741.

Brown, Susan L. and Matthew R. Wright. 2017. “Marriage, Cohabitation, and Divorce in Later Life.” Innovation in Aging 1(2): 1-11.

Carney, Maria T., Janice Fujiwara, Brian E. Emmert Jr., Tara A. Liberman, and Barbara Paris. 2016. “Elder Orphans Hiding in Plain Sight: A Growing Vulnerable Population.” Current Gerontology & Geriatrics Research.

Center for Retirement Research at Boston College. 2024 (forthcoming). “Healthcare and Long-Term Care Risks in Retirement: A Review of Existing Literature.” Prepared for Jackson National. Chestnut Hill, MA.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 2010. “Estimated Financial Effects of the ‘Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act,’ as Amended.” Memorandum from Richard S. Foster (April 22). Washington, DC.

Congressional Research Service. 2023. “Long-Term Care Insurance: Overview.” (July 21). Washington, DC.

Genworth Financial, Inc. 2023. “Cost of Care Survey.” Richmond, VA.

Giese, Christopher, Allen Schmitz, Annie Gunnlaugsson, and Evan Pollock. 2022. “2022 WA Cares Fund Actuarial Study.” Commissioned by the Office of the State Actuary. Seattle, WA: Milliman.

Giese, Christopher, Jill Herbold, Jeremy Cunningham, Annie Gunnlaugsson, and Dean Johnson. 2021. “WA Cares Fund Savings for the Medicaid Program.” Commissioned by the Office of the State Actuary. Seattle, WA: Milliman.

Gleckman, Howard. 2012. “The Rise and Fall of the CLASS Act: What Lessons Can We Learn?” In Universal Coverage of Long-Term Care in the United States: Can We Get There?, edited by Douglas Wolf and Nancy Folbre. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Gruber, Jonathan and Kathleen McGarry. 2023. “Long-term Care in the United States.” Working Paper 31881. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

King, Valarie and Mindy E. Scott. 2005. “A Comparison of Cohabiting Relationships among Older and Younger Adults.” Journal of Marriage & Family 67(2): 271-285.

LIMRA. 2022. “Do Consumers Really Understand Long-Term Care Insurance?” News Release (November 15). Windsor, CT.

LTSS Trust Commission. 2021. WA Cares Fund Risk Management Framework. Olympia, WA: WA Cares Fund.

Munnell, Alicia H. 2024. “Washington State’s Long-Term-Care Program Could Be Killed by Ballot Initiative.” Blog Post (July 8). MarketWatch: New York, NY.

Munnell, Alicia H. and Josh Hurwitz. 2011. “What is ‘CLASS’? And Will It Work?” Issue Brief 11-3. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Nationwide. 2023. “The Nationwide Retirement Institute 2023 Long-term Care Survey.” Columbus, OH.

Spillman, Brenda C., Eva H. Allen, and Melissa Favreault. 2020. “Informal Caregiver Supply and Demographic Changes: Review of the Literature.” Prepared for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Washington, DC.

Stepler, Renee. 2017. “Led by Baby Boomers, Divorce Rates Climb for America’s 50+ Population.” Washington, DC: Pew Research Center.

U.S. Congress Joint Economic Committee. 2019. “An Invisible Tsunami: ‘Aging Alone’ and Its Effect on Older Americans, Families, and Taxpayers.” (January 24). Washington, DC.

Warshawsky, Mark J. 2022. “The Second Failed Attempt at Public Insurance For Long-Term Services And Supports.” Health Affairs Forefront.

Wettstein, Gal and Alice Zulkarnain. 2019. “Will Fewer Children Boost Demand for Formal Caregiving?” Working Paper 2019-6. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Endnotes

- LIMRA (2022) estimates that only 3 percent of Americans have long-term care insurance (LTCI). For a brief overview of LTCI, see Congressional Research Service (2023). ↩︎

- Genworth Financial (2023). Not all of the cost goes directly to the caregiver’s wages. Often, home health networks, administrators, and travel costs can take a substantial portion of the total cost. ↩︎

- Gruber and McGarry (2023). ↩︎

- Genworth Financial (2023). ↩︎

- For households where one spouse is still living in the community, their house can be exempt from the Medicaid asset limits. In some states, the community living spouse’s 401(k) or IRA assets can also be exempt. Additionally, a certain amount of the couple’s income is protected to prevent spousal impoverishment, although the rules vary by state. ↩︎

- Spillman, Allen, and Favreault (2020). ↩︎

- King and Scott (2005); Brown and Lin (2012); Stepler (2017); Brown and Wright (2017); and Wettstein and Zulkarnain (2019). ↩︎

- U.S. Congress Joint Economic Committee (2019). ↩︎

- Carney et al. (2016). ↩︎

- For a more detailed summary of the CLASS Act, see Munnell and Hurwitz (2011). ↩︎

- This concern was cited as a serious risk by the Chief Actuary for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (2010) and by a joint work group from the American Academy of Actuaries and the Society of Actuaries (see American Academy of Actuaries (2009, 2011). ↩︎

- See Gleckman (2012) for a discussion of the recent history of federal long-term care policy up through the enactment of CLASS. ↩︎

- Benefits will be paid to Washington State residents, at least 18 years old, who are either temporarily or permanently vested, and meet a threshold for long-term care needs. Specifically, this threshold (which has not yet been finalized) is likely to require that individuals are unable to complete at least three activities of daily living – such as bathing and eating – over the last seven days without monitoring, encouragement, or set-up assistance. This requirement should capture people with mild, as well as severe, cognitive impairment. Employees are temporarily vested if they have worked at least 500 hours per year for three years within the past six years from the date of application of benefits. Employees are permanently vested if they have worked at least 500 hours per year for at least 10 years. Upon becoming eligible, individuals will receive coverage of services, paid to providers, up to a lifetime total of $36,500 adjusted for inflation. Services could include in-home personal care, assisted living and nursing home care, respite for family caregivers, transportation, meals, home modifications, adaptive equipment, etc. ↩︎

- See Aaron (2022) for more details on the program’s design and the changes since its enactment. ↩︎

- In addition, the amendments authorized Native American tribes, which the original legislation did not cover, to opt in. ↩︎

- The total number of approved exemptions from these groups, effective on or before July 1, 2024, was 61,783 out of a state workforce of 3.5 million. ↩︎

- Warshawsky (2022). ↩︎

- Survey data suggest that some people may mistakenly believe they have long-term care coverage through another insurance product. See LIMRA (2022) and Nationwide (2023). ↩︎

- Since the state does not have an income tax, it will need the help of the Internal Revenue Service to enforce this provision. ↩︎

- Giese et al. (2022). ↩︎

- Washington also has a risk management framework that monitors the program’s finances and alerts the legislature as to the solvency issue, in which case the Commission would recommend adjustments to the program (LTSS Trust Commission 2021). ↩︎

- See Aaron (2022) and Giese et al. (2021). ↩︎

- For example, the legislature added the requirement that the need for long-term care services or supports has to be projected to last at least 90 days. ↩︎

- The Commission has recommended this change to the legislature. If the legislation passes, the proposal would then have to go to the voters for approval, as it requires a constitutional amendment. ↩︎

- See Ballotpedia (2024) and Munnell (2024). ↩︎