When Retirees Go Back to Work Is It a Sign of a Strong Labor Force — or a Recession?

Geoffrey T. Sanzenbacher is a columnist for MarketWatch and a professor of the practice of economics at Boston College. He is also a research fellow at the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

What “unretirements” can tell us about the job market.

These days, economists find themselves in a fog with respect to the labor market.

First, there’s the fact that the monthly jobs report for September was released a month late and the October report was cancelled entirely. But, on top of that, the data that do exist are giving mixed signals. The number of jobs being added to the economy has slowed to a crawl. But, the unemployment rate has remained low by historical standards. Job openings and worker quits – which respectively measure how easy it is to get a job and how comfortable people feel leaving one – are falling quickly (bad) but also in line with historical averages (good). What’s going on?

In these situations, I turn to any measure of labor market health that I can find. As a retirement researcher, one of my personal favorites is the unretirement rate. The unretirement rate is exactly what it sounds like: the share of workers who claim to be retired at a given point and then report that they are working a year later.

Unretirement is a way for older workers to solve both financial and nonfinancial problems. Some retirees face financial pressures because of low savings rates, high medical costs, and longer lifespans; and some find that retirement isn’t what they expected and may miss the social connection and sense of purpose that can come with a job.

One could imagine that high rates of unretirement are a bad sign for the economy, for example because the stock market is down and retirees need to work to recoup their losses. But, in general, the research suggests that the stock market does not drive behavior around retirement. Instead, workers tend to unretire when it is easiest to do so – i.e., when the job market is strong. So, looking at the rate of unretirement can tell us something about the broader job market and just where it might be going. When the unretirement rate is high, the labor market is likely to be good.

To examine where the unretirement rate stands, I went to the same survey from which those monthly employment reports (usually) come – the Current Population Survey (CPS). I identified workers ages 55 and over who claimed to be retired when they were interviewed by the CPS. Then, I used the longitudinal feature of the CPS to follow up with those same individuals when they were interviewed one year later. Those who said that they were employed at that time were said to have unretired.

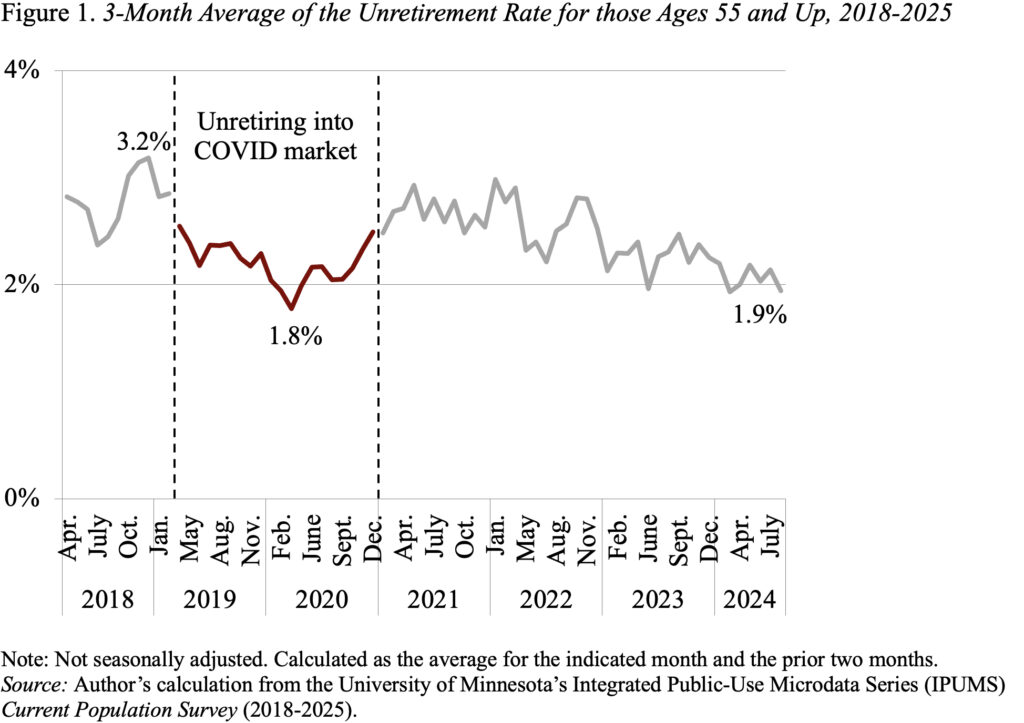

Figure 1 shows the share of retirees who unretired from just before COVID until the most recent data available. (The time period on the graph indicates when the person was first interviewed – i.e., someone who said they were retired in August 2024 and working in August 2025 contributes to the August 2024 unretirement rate). The graph highlights in red the period when people would have been unretiring into the COVID job market – i.e., people retired between March 2019 and December 2020 – and who would have been unretiring from March 2020 to December 2021.

The figure doesn’t paint an especially flattering picture of the current job market. Just prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the unretirement rate averaged nearly 3 percent. That time period was at the end of a long economic expansion, so the unretirement rate then could be looked at as a benchmark for a “good” job market. For people who would have been unretiring into the COVID labor market, that number averaged 2.2 percent and bottomed out at 1.8 percent. For the most recent data available, the rate looks a lot more like the COVID rate than the expansion rate. The most recent unretirement rate available sits at just 1.9 percent.

At a time when labor market data are scant and conflicting, any measure can help. The low rate of unretirement today suggests that older workers are finding it difficult to reenter the labor market and thus staying on the sidelines. In the coming months, I’m keeping my eye on whether the rest of the labor market data start to look similarly bleak.