Why Does Australia’s Retirement System Outrank America’s?

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Our Social Security program is well-structured, but with one major flaw.

I’ve been scratching my head since President Trump announced in early December that the administration is considering developing a national retirement savings system like Australia’s superannuation program. Yes, our system is not perfect, but it’s not clear what we get from Australia at this stage of the game.

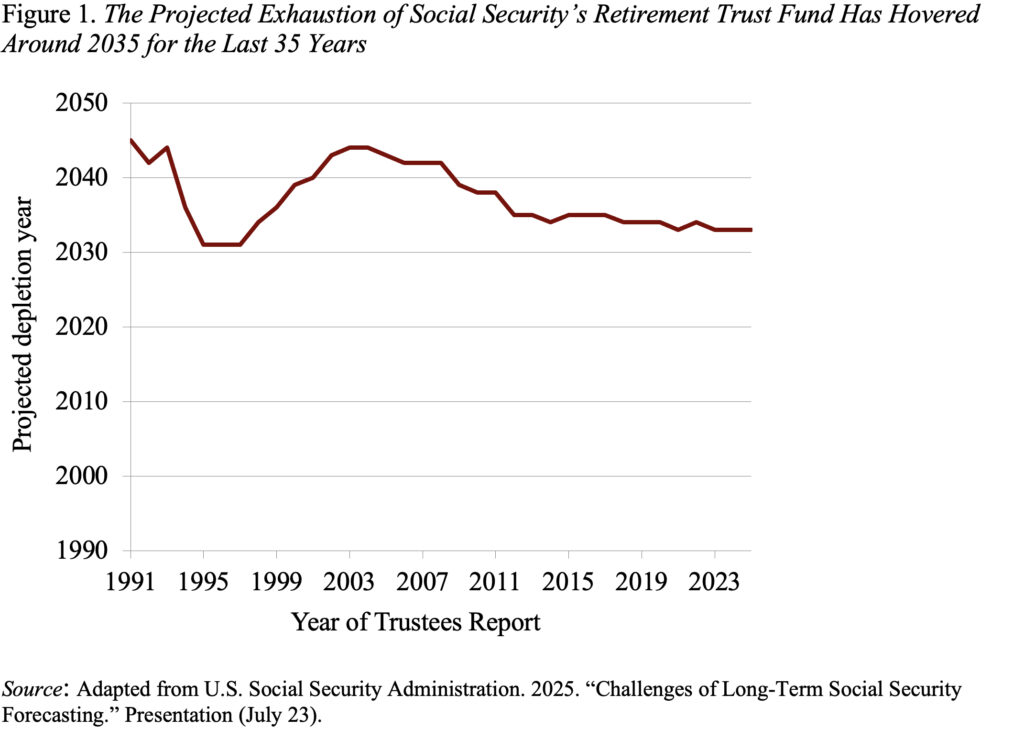

That’s not to say that the Australian system doesn’t deserve high grades. In fact, Mercer’s latest Global Pension Index awards the Australian system a B+, while the U.S. system gets only a C +. It’s pretty clear why we get a low grade. In 2033, the reserves in Social Security’s retirement trust fund will be exhausted, and the government will be forced to cut benefits by 23 percent. This is not new news. The exhaustion of the trust fund has been on the books since the early 1990s (see Figure 1), but, over the last 35 years, we haven’t taken a single step to head off the collision. That is ridiculous. But the imminent crisis reflects a failure of Congressional will, not a failure with the design of the program.

The U.S. Social Security system has been the most successful public program in the nation’s history. It is financed by a tax on workers’ earnings and provides a guaranteed lifetime income to retirees, their spouses, and survivors. Benefits are structured so the lower-paid receive proportionately higher benefits than the high earners, and the benefits of high earners are also subject to taxation under the federal income tax. This progressive benefit design is somewhat undermined, however, by the fact that high earners live forever while the low-paid die early.

The main critique of the Social Security program, however, is that it operates on a pay-as-you-go basis, which makes it very vulnerable to demographic shifts. That arrangement was not the original intention; the 1935 legislation called for the accumulation of a trust fund – like an insurance company. But amendments in 1939 changed the nature of the program, making it easier to provide full benefits to early cohorts, many of whom had fought in World War I and endured the Great Depression. These benefits paid to the early retirees, however, did not come for free. If earlier cohorts had received benefits based on their contributions and interest, we would have a large trust fund today and the payroll tax rate would be almost 4 percentage points lower than required.

On top of Social Security, we have a layer of employer-sponsored retirement plans – primarily, 401(k) plans that allow workers to accumulate piles of assets. This supplementary tier could also contribute to our low grade because at any moment only half of private sector workers are participating in such a plan. Moreover, the financial services industry is doing everything to restructure distributions from a pile of assets to a stream of retirement income. But people don’t buy annuities and remain reluctant to tap their accumulations. Moreover, we forgo a lot of tax revenues by providing favorable tax treatment to savings through retirement-sponsored plans.

So, if that’s why we get a C+, why do the Australians get a B+? The Australian system is just the inverse of ours. Their basic plan, which was created in 1992, is a defined contribution system where employers currently pay a tax-favored 12 percent of the employee’s earnings into funds that invest in equities, bonds, and other assets. Some voluntary contributions can be paid to these funds on a tax-favored basis by higher-paid employees and by the self-employed. Participants have total access to their superannuation assets at age 65 or any time after age 60 (earlier if born before 1964) if they have stopped work. Those who end up with inadequate resources in retirement can receive income from Australia’s means-tested Age Pension, which was first established in 1908.

The appeal of the Australian system to organizations ranking national retirement systems is that the main plan is fully funded and protected from demographic shifts, and the Age Pension ensures that no one falls below any adequate standard of living. On the other hand, one could argue that extensive reliance on the accumulation of balances obscures the goal of achieving a secure stream of income and integrating proceeds from the basic system with the Age Pension seems very complicated.

I’m happy to give the Australians their due, but I’m hard-pressed to see how their design offers any guidance to improving the U.S. system. It’s clear what we need to do – restore balance to Social Security and expand coverage to supplementary savings for all workers. We, too, should be able to get a B+.