Will Auto-IRAs Help Households Cope with Emergency Expenses?

The brief’s key findings are:

- State auto-IRA programs help workers build retirement savings, though participants can withdraw their contributions without taxes or penalties.

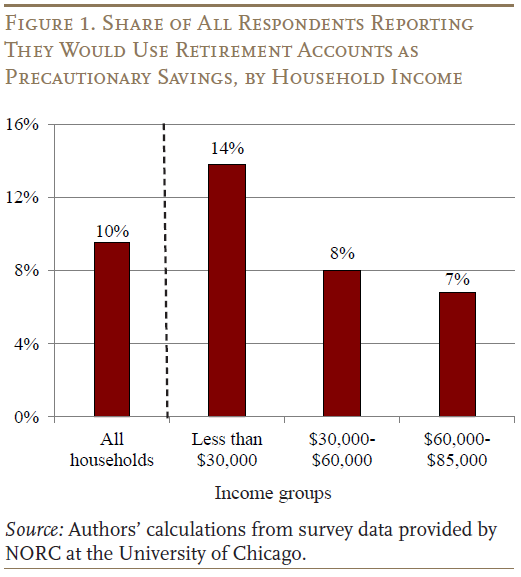

- But a new CRR survey of low- to moderate-income workers shows that only 10 percent would tap such an account for an emergency.

- Most workers prefer to keep the savings intact for retirement and have misperceptions about taxes and penalties.

- Whether the withdrawal process is described as “hard” or “easy” had little effect on withdrawals.

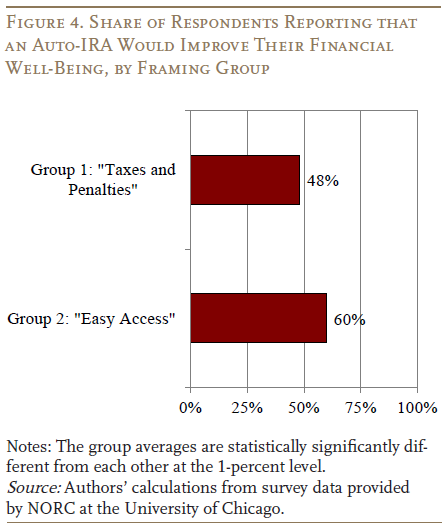

- But the “easy access” framing did make workers more enthused about auto-IRAs, which could help participation.

Introduction

The most effective way to save for retirement is through a workplace-based retirement plan, but many workers lack access to one. To help close this gap, a number of states have adopted programs that require employers without a plan to auto-enroll their workers in an Individual Retirement Account (IRA).

These accounts use the Roth structure, so workers pay taxes on their contributions up front, allowing them to withdraw contributions at any time without taxes or penalties. Such flexibility may be especially valuable to lower-paid workers, who often lack precautionary savings for emergencies. However, several factors may prevent them from taking money out – a desire to leave retirement savings intact, misperceptions about taxes and penalties, and the potential administrative hassle of withdrawing funds.

This brief, which is based on a recent paper, asks a group of low- and moderate-income workers whether they would tap auto-IRA savings in an emergency and if not, why? It also tests whether the way the withdrawal process is described affects workers’ withdrawal intentions.1

The discussion proceeds as follows. The first section offers background on the state programs. The second section summarizes the survey used in this analysis. The third section presents the results. The final section concludes that many workers may avoid tapping their auto-IRAs in an emergency due to a desire to keep retirement savings intact and misperceptions about taxes and penalties. Describing account assets as either harder to tap or more easily accessible has little impact on withdrawal intentions, but the easy-access framing makes workers more enthusiastic about the auto-IRA, which could boost participation in the program.

Background

At any point in time, only about half of private sector workers are covered by an employer-sponsored retirement plan and very few save without them.2 In the absence of a federal solution, states have taken the initiative. Currently, ten states have implemented auto-IRA programs, while another six are in the planning stages.3 Notably, the Roth structure of these IRAs means that participants can withdraw their contributions tax-free at any time, though their investment earnings may be subject to taxes and/or penalties.4

While auto-IRAs are intended for retirement saving, many participants could benefit from the ability to withdraw their funds in an emergency.5 Auto-IRA participants tend to have lower incomes and less liquidity than their counterparts in traditional employer plans – so the ability to tap their accounts may particularly help them avoid using high-cost forms of borrowing. Recognizing this need for precautionary savings, one state auto-IRA program, MarylandSaves, diverts the first $1,000 of contributions into a separate account earmarked for emergencies.

For several reasons, however, it remains unclear whether auto-IRA participants will choose to tap their accounts when in need. First, unless the program has an explicit precautionary savings component, participants may consider funds in an auto-IRA as earmarked for retirement and choose not to take withdrawals.6 Second, workers may not understand the distinction between Roth and traditional retirement accounts, which could lead them to overestimate the taxes and penalties for early withdrawals from auto-IRAs. Finally, workers could find it cumbersome to submit the paperwork to initiate withdrawals, especially during an emergency. Adding to this ambiguity, program websites for the various live auto-IRA programs use different language to describe the withdrawal process, with some programs seeming to encourage withdrawals more than others.

Given that the live auto-IRA programs are still at an early stage, little real-world evidence exists on participant withdrawal behavior. Hence, this study uses a survey to explore whether workers are likely to use auto-IRA accounts for precautionary savings and, if not, what are the reasons; it also tests whether the communications approach matters.

Data and Methodology

The survey was administered by NORC at the University of Chicago to their nationally representative AmeriSpeak panel. Participants were eligible if they had income below $85,000 (the bottom three quintiles of household income).7 The survey was fielded online in August 2023 and included 3,213 respondents who were randomly assigned to two groups.8

Both groups were asked whether they would withdraw funds from a hypothetical IRA in an emergency to cover a $400 expense – a commonly used benchmark of financial fragility.9 Respondents who chose not to tap their accounts were asked why not. Finally, all respondents were asked how having some savings in an auto-IRA would affect their financial well-being.

The distinction between the two groups was that they were given different descriptions of the process for withdrawing money from the IRA. This design allowed us to test the impact of two different communication approaches on participants’ intended withdrawals and enthusiasm for the auto-IRA.

Group 1: Taxes and Penalties. Respondents in the first group were told to imagine a hypothetical scenario in which they have some savings in an IRA. They were not told that the account is a Roth; instead, they were informed that withdrawals could trigger taxes and penalties.10 Respondents were then asked how they would cover a $400 emergency expense in this hypothetical scenario – which included the option of “withdrawing money from my retirement plan/account.”

Several of the live auto-IRA programs have similar wording about withdrawals on their websites.11 While this statement is typically followed by a clarification that participants can always access their contributions tax-free, having participants first read about the potential for taxes and penalties could lead them to overestimate the cost of withdrawing funds in an emergency and nudge them toward other, more costly coping strategies such as taking on high interest-rate debt.

Group 2: Easy Access. Respondents in the second group were also asked to imagine a hypothetical scenario with savings in an IRA. However, the framing of the withdrawal process for this group excluded any mention of taxes and penalties; instead, respondents were told that they could tap their savings easily at any time by going online or calling a hotline. As before, respondents were then asked how they would cover the $400 emergency expense in this scenario.

A couple of live auto-IRA programs currently have similar wording on their websites.12 The inverse of Group 1, these programs first describe the withdrawal process as “simple” then clearly explain how contributions may be withdrawn tax-free, while noting that investment earnings are treated differently.

Results

This discussion starts with the core exercise, which combines the responses from the two groups to assess how many people intend to tap their hypothetical IRA in an emergency and, for those who choose not to, the reasons why.13 It then turns to the communications test results.

Using Auto-IRAs as Precautionary Savings

The results show that 10 percent of all respondents reported that they would withdraw money from their retirement account to cover a $400 expense (see Figure 1).14 Unsurprisingly, lower-income respondents were more likely to say they would tap their retirement accounts.15

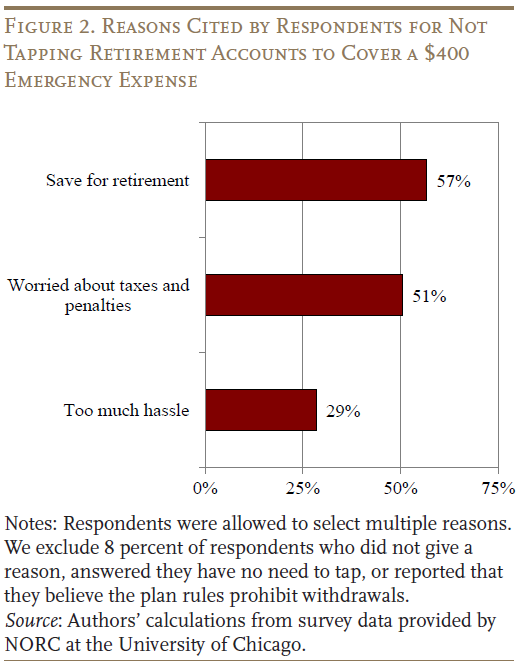

Participants not tapping their accounts cited various reasons why; again, these results are combined for both groups (see Figure 2). The two most common reasons are wanting to save the funds for retirement and worries about taxes and penalties. A smaller share of respondents consider the withdrawal process too complicated. Given that many workers were worried about the perceived tax implications of withdrawing, the next question is whether the wording of program communications (“Taxes and Penalties” vs. “Easy Access”) affected intended behavior.

Taxes and Penalties vs. Easy Access

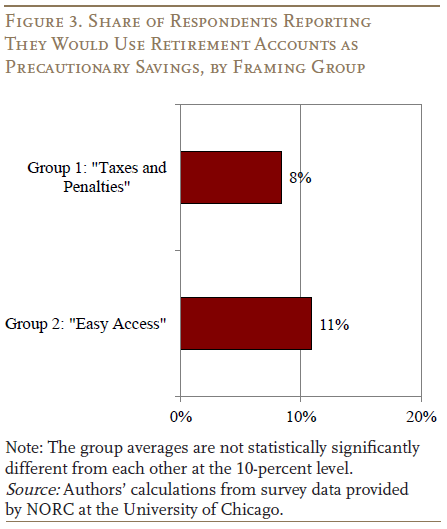

Contrary to expectations, framing the account as easily accessible did not seem to increase withdrawals – the difference between the two groups is not statistically significant (see Figure 3).16 Clearly, auto-IRA participants need more than a shift in language to divert them from familiar forms of borrowing in an emergency.

Regardless of whether workers view auto-IRAs as hard or easy to access, the program may help them meet long-run saving goals and feel more secure. Indeed, as shown in Figure 4, substantial shares of respondents in both groups said that having some savings in an auto-IRA would improve their financial well-being (the rest reported no impact).17 While 48 percent of respondents in the “Taxes and Penalties” group reported that having an auto-IRA would improve their well-being, 60 percent of those in the “Easy Access” group did so, and this difference is statistically significant.

Conclusion

Auto-IRA programs provide a retirement savings vehicle for workers whose employer does not offer one, and can serve a secondary purpose as precautionary saving, helping workers avoid high-cost forms of borrowing. However, households may refrain from tapping their accounts in an emergency because they want to save for retirement, are worried about perceived taxes and penalties, or think the process will be too much hassle.

Using a survey targeting low- to moderate-income workers, this brief finds that 10 percent of workers say that they would use auto-IRA savings to cover an unexpected $400 expense if they had access to the program. The primary deterrents to tapping auto-IRAs are a desire to save for retirement and concern about perceived taxes and penalties. Describing auto-IRAs as easily accessible on program websites is probably not enough to change withdrawal behavior and divert participants from familiar forms of borrowing. Nevertheless, compared to an alternative framing that cautions of potential tax consequences from withdrawals, the easy-access framing does improve workers’ enthusiasm for the program. Since participants are more satisfied when they believe they can access their accounts easily, educating workers about the program’s Roth structure might increase take-up and ultimately lead to more retirement savings.

References

Beshears, John, James J. Choi, Christopher Harris, David Laibson, Brigitte C. Madrian, and Jung Sakong. 2020. “Which Early Withdrawal Penalty Attracts the Most Deposits to a Commitment Savings Account?” Journal of Public Economics 183: 104144.

California State Treasurer. 2023. CalSavers 2023 Reports. Sacramento, CA: CalSavers Retirement Savings Board.

Center for Retirement Research at Boston College. 2015. “Report on the Design of Connecticut’s Retirement Security Program.” Special Report. Chestnut Hill, MA.

Center for Retirement Research at Boston College. 2024. Closing the Coverage Gap. Chestnut Hill, MA.

Chalmers, John, Olivia S. Mitchell, Jonathan Reuter, and Mingli Zhong. 2021. “Auto-Enrollment Retirement Plans for the People: Choices and Outcomes in OregonSaves.” Working Paper 28469. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Chen, Anqi. 2019. “Why Are So Many Households Unable to Cover a $400 Unexpected Expense?” Issue in Brief 19-11. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Dushi, Irena, and Brad Trenkamp. 2021. “Improving the Measurement of Retirement Income of the Aged Population.” ORES Working Paper Series 116. Washington, DC: Social Security Administration.

Georgetown Center for Retirement Initiatives. 2024. State Program Performance Data – Current Year. Georgetown Center for Retirement Initiatives.

Guttman-Kenney, Benedict, Paul D. Adams, Stefan Hunt, David Laibson, Neil Stewart, and Jesse Leary. 2023. “The Semblance of Success in Nudging Consumers to Pay Down Credit Card Debt.” Working Paper 31926. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Illinois State Treasurer. 2023. Secure Choice Performance Dashboards. Springfield, IL.

Liu, Siyan and Laura D. Quinby. 2024. “Would Auto-IRAs Affect How Low-Income Households Cope with Emergency Expenses?” Working Paper 2024-11. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Oregon Retirement Savings Board. 2023. Monthly OregonSaves Program Data Reports. Salem, OR: Oregon State Treasury.

Quinby, Laura D., Alicia H. Munnell, Wenliang Hou, Anek Belbase, and Geoffrey T. Sanzenbacher. 2020. “Participation and Preretirement Withdrawals in Oregon’s Auto-IRA.” Journal of Retirement 8(1): 8-21.

Sabelhaus, John. 2022. “The Current State of U.S. Workplace Retirement Plan Coverage.” Working Paper No. 2022-07. Philadelphia, PA: Wharton Pension Research Council of the University of Pennsylvania.

Scott, John, and Andrew Blevins. 2020. “Oregon State Retirement Program Growing during Pandemic—despite Some Worker Withdrawals.” The Pew Charitable Trusts. October 20, 2020.

Scott, John, and Mark Hines. 2022. “Many in Illinois Retirement Savings Program Feel Their Financial Security Is Improving.” The Pew Charitable Trusts. April 18, 2022.

Thaler, Richard H. 1985. “Mental Accounting and Consumer Choice.” Marketing Science 4: 199-214.

Thaler, Richard H. 1999. “Mental Accounting Matters.” Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 12(3): 183-206.

U.S. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking, 2022. Washington, DC.

U.S. Census Bureau. 2023. Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement. Washington, DC.

Endnotes

- Liu and Quinby (2024). ↩︎

- Sabelhaus (2022) and Dushi and Trenkamp (2021) ↩︎

- The ten states are California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Maine, Maryland, New Jersey, Oregon, and Virginia. Another six states – Minnesota, Nevada, New York, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Washington – have passed auto-IRA legislation and are preparing to launch their programs (Center for Retirement Research at Boston College 2024). ↩︎

- Investment earnings from Roth IRAs may be subject to taxes and penalties depending on the age of the account, the age of the participant, and the purpose for which the withdrawal is used. ↩︎

- See Beshears et al. (2020) and Center for Retirement Research at Boston College (2015). ↩︎

- For example, see Thaler (1985, 1999). ↩︎

- Individuals in the 2023 Annual Social and Economic Supplements of the Current Population Survey with household income below $85,000 have similar salaries as actual auto-IRA participants. Our survey also oversampled Black and Hispanic households and those living in states with up-and-running auto-IRA programs. ↩︎

- An additional group of participants was used simply to confirm the need for precautionary saving in the population studied and benchmark our results against prior studies. ↩︎

- For data on the $400 emergency expense question, see Chen (2019) and the Federal Reserve’s Survey on Household Economics and Decisionmaking. ↩︎

- See Liu and Quinby (2024) for the complete survey question. ↩︎

- For example, MyCTSavings and Colorado SecureSavings had similar wording as of September 2024. ↩︎

- For example, OregonSaves and RetirePathVA had adopted this approach as of September 2024. ↩︎

- Despite being prompted to think about a hypothetical auto-IRA, about one-third of respondents in Groups 2 and 3 stated that they do not own a retirement account, and hence could not tap it. Supplemental analysis in the paper shows that our results are robust to various assumptions about the behavior of these “never takers;” the main results (reported here) simply exclude those who rejected our treatments from the analysis. ↩︎

- To put this finding in context, the three oldest auto-IRA programs (OregonSaves, CalSavers and Illinois Secure Choice) currently report 15 to 21 percent of active participants making withdrawals each year (Quinby et al. 2020, Chalmers et al. 2021, California State Treasurer 2023, Illinois State Treasurer 2023, and Oregon Retirement Savings Board 2023). Of course, only some of these withdrawals were made in an emergency, as opposed to cash-outs at job change or workers leaving the program altogether. Relatedly, Scott and Blevins (2020) show that total withdrawals ticked up in March 2020 (with the onset of the COVID economic shutdown) compared to 2019, suggesting an increased need to tap these savings. ↩︎

- However, somewhat disappointingly, 43 percent of respondents still expected to borrow or sell even with the auto-IRA. ↩︎

- The failure of the easy-access message, while disappointing, is consistent with a recent study that also failed to deter households from accumulating revolving credit card debt (Guttman-Keney et al. 2023). ↩︎

- This result is consistent with the findings of Scott and Hines (2022) on improved self-reported financial security among participants in the Illinois Auto-IRA program. ↩︎