Will Changes to Multiple Employer Plans Put a Dent in the Coverage Gap?

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

The hurdles seem quite challenging.

We just released a report that explores the possibilities and limitations of Multiple Employer Plans (MEPs) to improve coverage in employer-sponsored retirement plans. The lack of consistent coverage – a pressing concern for the nation’s retirement income security – is driven by small employers.

A MEP is a retirement plan – generally a 401(k) – adopted by two or more employers and administered by a MEP sponsor (typically a trade or industry group or professional employment organization) that takes on the fiduciary burden and spreads the administrative, compliance, and cost burden across multiple employers.

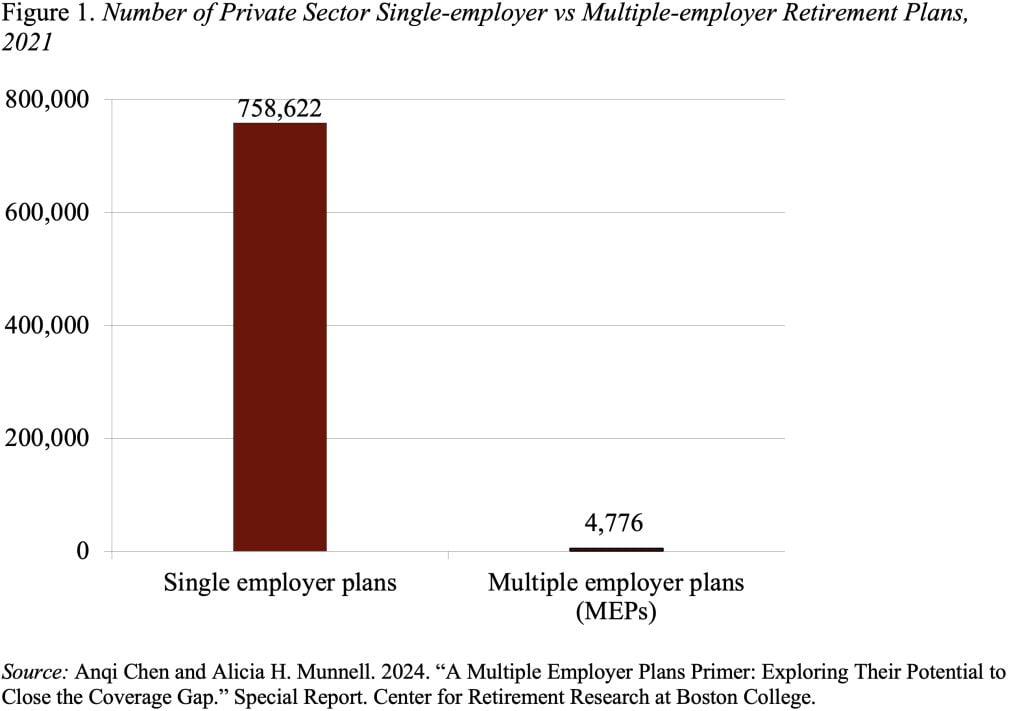

While MEPs have been around for decades, they have not moved the needle on coverage. In 2021, MEPs only represented 0.6 percent of total private-sector retirement plans (see Figure 1), covering roughly 5.7 percent of active participants. Two main restrictions of MEPs may have limited their adoption: 1) employers had to share a common bond; and 2) the whole MEP could lose its tax-qualified status if one employer within the group was not in compliance (the “bad apple” rule).

To increase participation, The SECURE Act of 2019 removed the “bad apple” restriction and created a new subclass of MEPs, called Pooled Employer Plans (PEPs), which are not limited to employers with a common bond. PEPs can only be established by a registered pooled plan provider (PPP), which takes on the role of named fiduciary and attends to plan administration, compliance, and auditing.

The removal of the common bond and bad apple restrictions has generated a lot of excitement, particularly among financial services firms. Indeed, PEPs have several potential advantages over the plethora of existing options for small employers. PEPs can reduce the administrative burden, the fiduciary responsibility and – perhaps – the cost of offering a plan, while maintaining the ability to select the provider of choice and offer employer matches.

Despite the enthusiasm, the initial uptake has been slow and PEPs may have a limited impact on the coverage gap for a number of reasons.

- Vast majority of small employers have never heard of PEPs or their parent, MEPs. Providers will not only have to convince employers that offering a retirement plan is valuable, but that joining a PEP is the right option for them.

- Cost savings may not materialize. First, it may be hard to beat the cost of providing a single employer plan, which has declined dramatically. Second, increased competition in the MEPs market could promote lower fees, but employers with weak bonds could also pay less attention to plan costs. Finally, plans that are free (or almost free) to the employers invariably pass on costs to plan participants.

- Employer retains some fiduciary responsibilities. While the PPP is the named fiduciary for a PEP, the employer is responsible for selecting the right provider, monitoring the fees, and determining whether the services offered are beneficial.

- Exiting may be difficult. An employer that gets bigger and wants to convert to a more customizable single-employer 401(k) may find it difficult and time-consuming to terminate its portion of the PEP.

- PEPs can also make mergers and acquisitions more challenging. Whether an employer wants to merge its plan with a buyer’s plan or fold an acquired employer’s plan into its own plan, the process is much easier with a single-employer plan.

- Future growth in PEPs may not mean greater coverage. It could simply mean employers are opting to join a PEP rather than offer their own single-employer plan.

Clearly widespread adoption of PEPs faces a lot of hurdles; only time will tell whether this less restrictive version of MEPs makes a dent in coverage.