Will You Need or Provide Long-Term Care?

The Trump Administration’s flouting of the U.S. Constitution brings to mind Benjamin Franklin’s often quoted statement that “[o]ur new Constitution is now established, and has an appearance that promises permanency; but in this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes.” Taxes also may not be as certain as Franklin had thought, with the recently passed budget resolution allowing for $5.3 trillion in tax cuts over the coming decade.

But that aside, almost as certain as death and taxes is the likelihood that sometime during our lives we will be either caregivers or care recipients – or both. The problem is that it’s difficult to predict when and for how long we will be receiving or providing care or the level of care.

This challenge is especially problematic for women. They are much more likely to be thrust into a caregiving role and, if married to men, are much more likely to outlive them both because women, on average, live longer than men and because in heterosexual couples they are likely to be younger. As a result, when women do need care, they are less likely to have a spouse available to step in, which is one of the reasons that more than two-thirds of residents of nursing homes are women.

Population-Wide Likelihood of Needing Care

It’s much easier to predict the need for care on a population basis than individually, but those population numbers can inform individual prospects of needing care. Researchers at the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College have crunched the numbers of various studies and in their 2021 report, “What Level of Long-Term Care Services and Supports Do Retirees Need?,” estimate overall long-term care needs. A recent update of these data show that only about a fifth of retirees will need no assistance at all during their lives and a fifth will need extensive services. The remaining 60 percent of seniors will have either low (25 percent) or moderate care needs (37 percent).

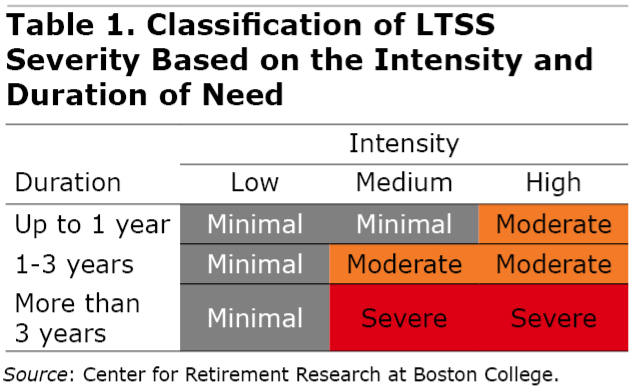

But what do these categories mean? The researchers, Anek Belbase, Anqi Chen, and Alicia H. Munnell, look at both the level and the duration of care. In terms of level of care, they define low intensity as needing assistance with one “instrumental” activity of daily living (e.g., money management, cooking, shopping); moderate as requiring assistance with one activity of daily living (e.g., bathing, toileting, eating); and high as having dementia or requiring assistance with two or more activities of daily living.

In terms of length of care needs, they define short as up to a year, medium as one to three years, and long-term as more than three years. The result is shown in Table 1.

Filling in the percentages yields Table 2.

All of these percentages apply to individuals at age 65. Again, these figures are very useful for population-wide predictions, but less useful for individuals planning for their own futures.

Predictive Factors

However, the statistics revealed individual attributes that offer some useful insights. Looking at whether a 65-year-old is married is somewhat predictive of being less likely to require extensive care later in their lives. For instance, married women are more likely to need no assistance and less likely to have severe needs than unmarried women. Those with more education, White individuals, and those in better health are similarly more likely to be in better shape in terms of their care needs.

Extrapolating from the Population Level to the Individual

Combining all these attributes, clearly a Black unmarried woman who did not graduate from high school and is in poor health at age 65 is much more likely to need extensive long-term care than a White married man with a college degree who reports being in good health at the same age. Unfortunately, these attributes are almost exactly misaligned with the ability to pay for care.

It should be possible to create a calculator for individuals to use to get some idea of their own likelihood of needing care. If it were combined with estimates of the cost of care in their region, it could be used in financial planning to provide some idea of how much money they can anticipate needing to spend. Such a calculator would not be conclusive since costs are largely determined by the setting where care is provided — home, assisted living, or nursing home — and whether family members can provide unpaid care, but it would offer more guidance than appears to be available anywhere today.

For more from Harry Margolis, check out his Risking Old Age in America blog and podcast. He also answers consumer estate planning questions at AskHarry.info. To stay current on the Squared Away blog, join our free email list.

Comments are closed.

So broadly speaking 60% of people age 65 will need 1 to 3 years or more of senior care of some sort. Have insurance companies used this information to roll out coverages reflecting these metrics? Is the government considering addressing this need? Can this care be provided “at home” unless severe?

So what does the gratuitous lead paragraph have to do with a relatively balanced and informative article on long term care needs?

Couldn’t agree more. I looked for some tie in in the balance of the article but couldn’t find any.