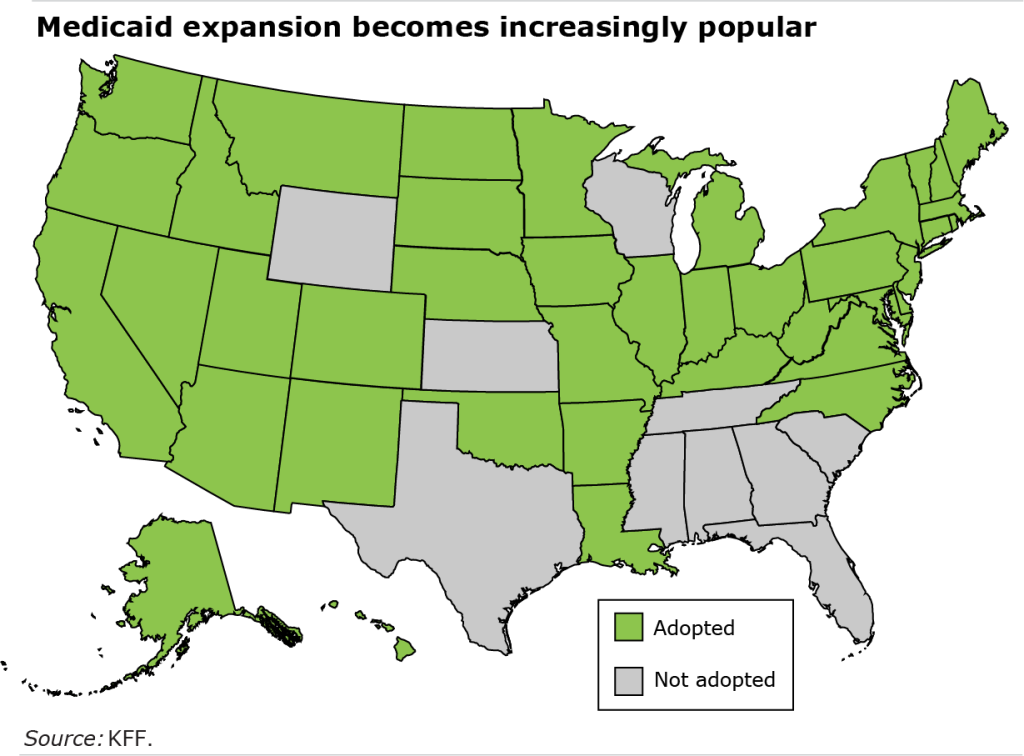

40 States Expanded Medicaid. The Benefits are Piling Up

In December, North Carolina will become the 40th state to expand its Medicaid program, providing health insurance coverage to some 300,000 more low-income workers, many of them for the first time.

It has taken the states a decade to reach that milestone, despite generous funding from the federal government under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) to defray the cost of expanding Medicaid coverage. The states that agreed to expand their programs have added more than 22 million people to their Medicaid rolls.

Most of the 10 states that are holdouts are in the South. They are not expanding their programs, despite Medicaid’s beneficial effects on Americans’ health, which have become widely recognized by politicians, policymakers and researchers.

The Medicaid expansion provision of the ACA went into effect in 2014 after a U.S. Supreme Court ruling said that states have the option of implementing it but are not required to. In the states that accepted the additional federal funding, Medicaid changed from an insurance program mainly for the poor and people with disabilities to one that also covered low-income workers earning up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level.

The states that have not expanded Medicaid have some of the highest rates of uninsured residents, but politicians argue their residents don’t want to devote more of their budgets to government aid. They include Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, who is highlighting his opposition to Medicaid expansion on the national campaign trail.

The benefits of expanding Medicaid to more people have become increasingly apparent, however, as new research documents the myriad ways the newly insured are being helped. Saying he views the coverage as crucial to North Carolinians’ well-being, Gov. Roy Cooper signed a bill expanding Medicaid after state lawmakers dropped their opposition to it.

In one new study in Health Affairs, expanding Medicaid reduced uninsured rates significantly in the most vulnerable parts of the Black and Hispanic communities. The researchers found that, in the states that agreed to cover more of their low-income workers, the census tracts with the most mortgage redlining historically have also seen the biggest drops in their uninsured populations.

Medicaid has also reduced mortality in working-age adults and in infants, provided crucial funding to rural hospitals in crisis and in danger of closing, and improved the quality of care and access to medical services.

In a recent report on the state Medicaid programs, the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities urged the states sitting on the sidelines to reconsider:

“It is time to join the rest of the country and ensure their state and residents gain access to the health and economic benefits that come with Medicaid expansion.”

Squared Away writer Kim Blanton invites you to follow us on Twitter @SquaredAwayBC. To stay current on our blog, please join our free email list. You’ll receive just one email each week – with links to the two new posts for that week – when you sign up here. This blog is supported by the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Comments are closed.

This doctor prescribes a healthy dose of skepticism. The paper highlights a 3.6% decrease in age 20-64 mortality and a 10% increase in insurance coverage, implying a 36% decrease in mortality among the newly insured. Now look at the leading causes of death among working age adults. Among 25-34 year olds, the second and third were homicide and suicide. We doubt if Medicaid was much help there. The rest were mislay things that take years to kill you – cancer and heart disease. Even if Medicaid coverage did increase access to health care, it wouldn’t show up so soon in the mortality data.

Is there a significant relationship between having health insurance and health status?

How much more is it costing taxpayers?

Now John, you should not be asking such embarrassing question!! Nor should one be pointing out the political bias in the write up. The vested interests in the “medicaid industry” (patients, providers, lobbyists, and others) do not care as to impact of such things on the national or state level fiscal situation. Florida spends more on medicaid than on education at all levels.