How Can We Fix Social Security’s Coming Cash Shortfall?

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Social Security proposals highlight challenges of benefit expansions.

We recently constructed a summary of the Social Security proposals of the 2020 presidential candidates. As part of that process, it seemed interesting to contrast the Social Security Expansion Act, proposed by Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) and Rep. Peter DeFazio (D-OR), with the Social Security 2100 Act, proposed by Rep. John Larson (D-CT), Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-CT), and Sen. Chris Van Hollen (D-MD). Both these proposals have been “scored” by the Social Security actuaries.

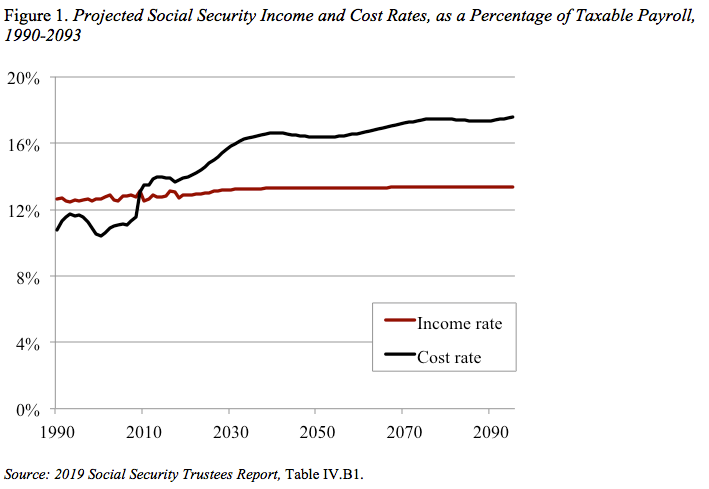

Remember the problem that needs to be solved. The Social Security actuaries project annual cash flow deficits over the next 75 years. These deficits reflect the combination of rising costs and a constant level of income. The increasing costs are the result of a slow-growing labor force and the retirement of baby boomers, which raises the ratio of retirees to workers. Moving from annual cash flows to a 75-year deficit requires calculating the difference between the present discounted value of scheduled benefits and the present discounted value of future taxes plus the assets in the trust fund. This calculation shows that Social Security’s long-run deficit is projected to equal 2.78 percent of covered payroll earnings.

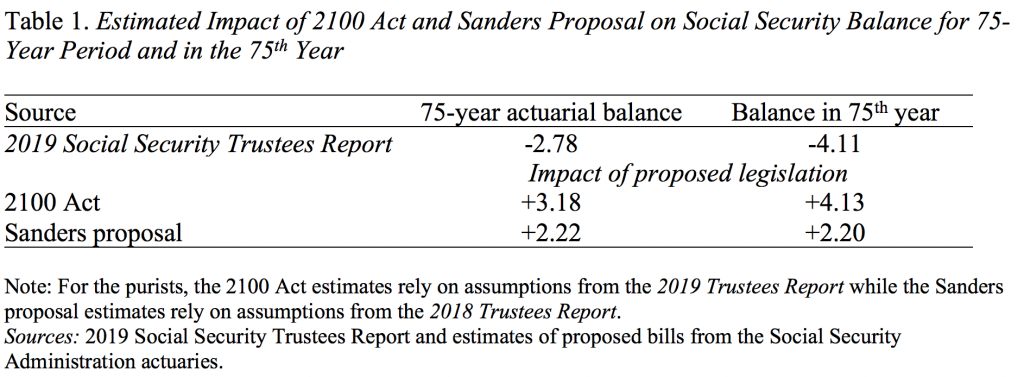

Although the Sanders proposal and the Social Security 2100 Act both involve increases in current benefits and recommend additional revenues, they differ markedly in their impact on the trust fund. The 2100 Act more than eliminates the 75-year deficit and has the program in balance in the 75th year, while the Sanders proposal does not close the 75-year deficit and has the program continuing to run large deficits at the end of the projection period (see Table 1).

On the benefit side, both bills propose an expansion of benefits. They would use the Consumer Price Index for the Elderly (CPI-E) to adjust benefits for inflation, increase the minimum benefit to 125 percent of the poverty threshold, and boost benefits generally by changing either the bend point or the percentage of earnings replaced in the first bracket of the benefit formula. The key difference here is that the general benefit increase in the Sanders bill is considerably larger than that in the 2100 Act.

On the revenue side, both bills would change the current payroll tax cap – albeit somewhat differently. The 2100 Act also raises the payroll tax rate. The Sanders bill broadens the payroll tax base to include investment income for higher-earning filers. Overall, the 2100 Act brings in about 17 percent more revenue than the Sanders bill over the next 75 years.

The bottom line is that larger benefit increases and smaller additional revenues means that the Sanders bill – unlike the 2100 Act – can solve only a part of the problem.