Why Do Some People Have a Will But Others Don’t?

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Without a will, asset dispersal can be problematic.

This blog post reports on the results of a survey that asked participants whether or not they have a will and why. Next week’s post will present the results of an experiment, for those without a will, to determine whether combining will-writing with the mortgage process – NOT a really good idea – would encourage more people to write wills.

The difference between having some wealth and relying solely on current income is huge. The most effective way to ensure that wealth transfers go to the intended recipients is for the donor to have a will. Without a will, assets can get dispersed among multiple heirs, which can be a particular problem for people whose major asset is their home.

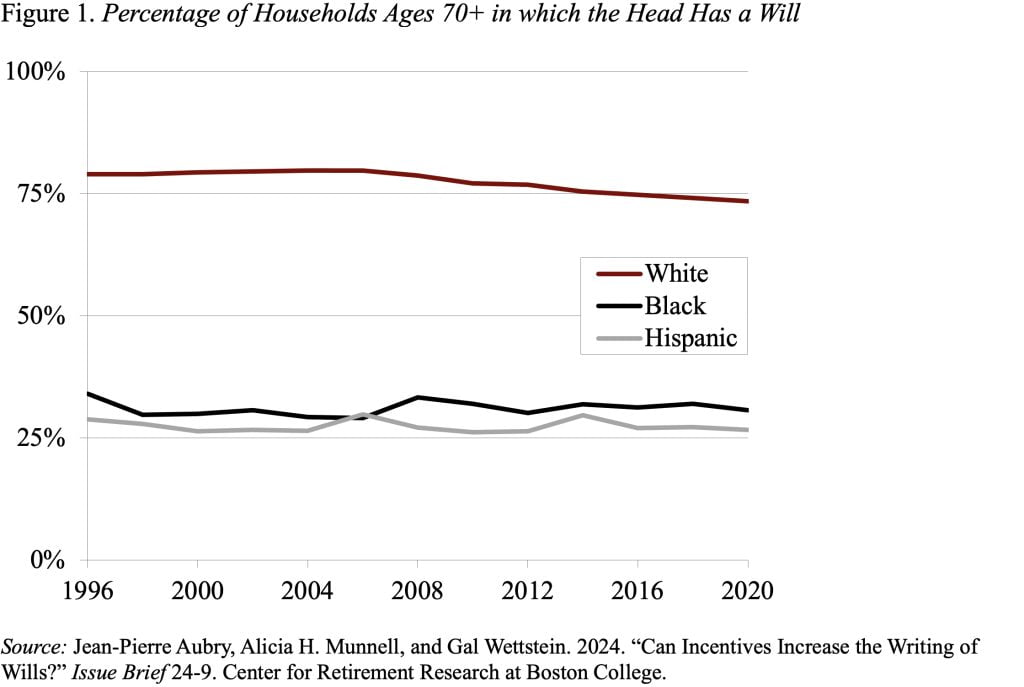

Despite the advantages of having a will, only about two-thirds of households with heads ages 70 and older had a will in 2020, and the share of White households with a will was more than twice that for Black and Hispanic households (see Figure 1).

The question of interest to us was whether targeted bequests can be increased through an intervention that promotes will-writing. To answer that question, we conducted a survey – using the AmeriSpeak panel run by NORC at the University of Chicago – that asked participants a series of questions about whether or not they have a will and why. Those without a will then participated in an experiment to determine whether various incentives would encourage them to write a will.

The survey showed that 34 percent of all respondents ages 25 and over had a will. These individuals were older, with more education, more likely to own a home, more likely to be White, and had somewhat higher income.

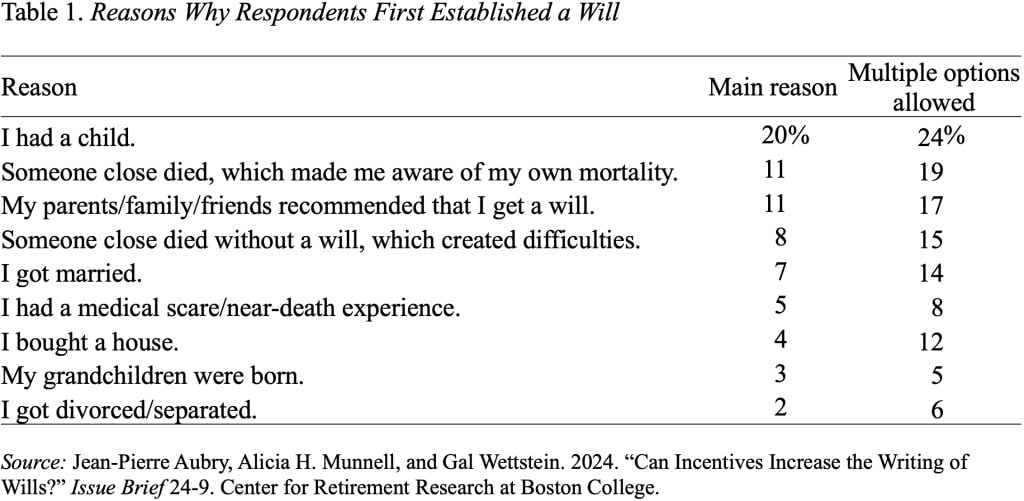

The most important motivating life event for writing a will was having a child (see Table 1). The next two reasons were more external: 1) someone close to the individual died, highlighting their own mortality; and 2) parents/family/friend recommended that the individual establish a will.

The survey also asked about intended recipients. The results show that children account for two-thirds of the total and grandchildren 7 percent. Other family members account for 18 percent and non-family – both unrelated individuals and religious or charitable organizations – 8 percent (see Figure 2).

The remaining 66 percent of individuals did not have a will. The major reason offered for not having written a will (44 percent) was: “I just haven’t got around to it yet.” This response is consistent with earlier studies showing procrastination is a major problem when it comes to will-writing. The second major reason is that some may have thought they had taken care of bequests, responding “I have named beneficiaries for most of my financial assets (401(k), life insurance, etc.)” Many of the other responses suggested that people were generally baffled by the process.

Next week’s blog post will report whether the prospect of including will-writing in the mortgage process would make things better or worse and what we learned from that.