Do We Have a Retirement Crisis?

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

The term doesn’t really matter, but about half of households are not doing so well.

Reporters always want to know “crisis” or “no crisis.” I don’t think the term is particularly important with respect to retirement security, but observation after observation paints the same picture – roughly half of households are not in good financial shape in retirement.

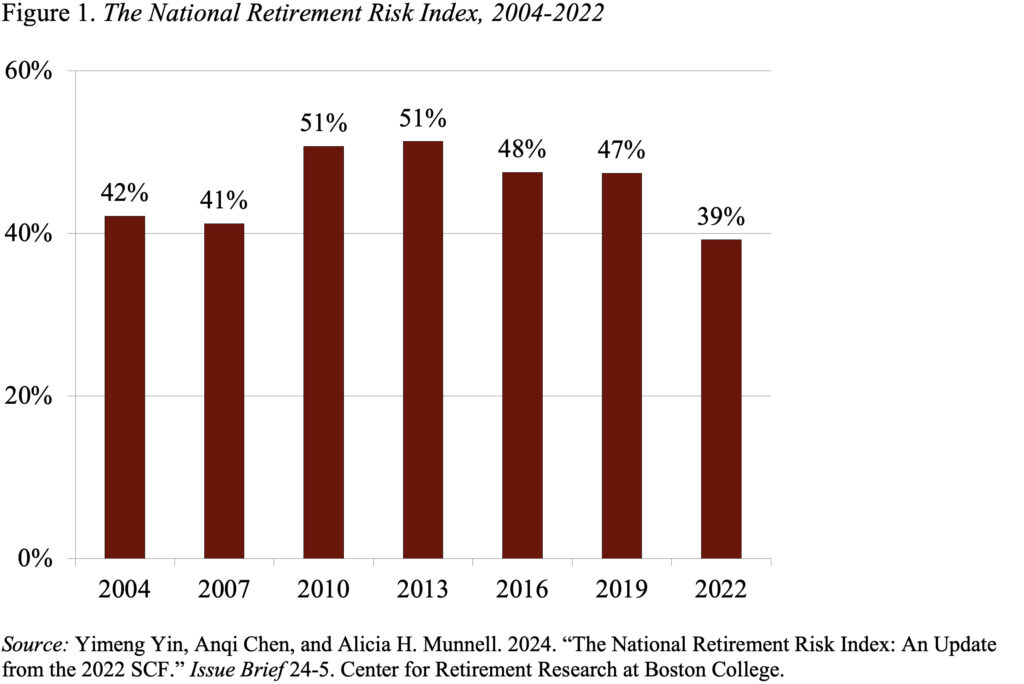

My best gauge of how well households are doing is the Center’s National Retirement Risk Index, which is based on the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances. The most recent estimate shows that 39 percent of today’s working-age households will not be able to maintain their standard of living in retirement (see Figure 1). Unique factors led to the lowest level since the NRRI first started – namely, rapidly rising home prices, new savings during the pandemic, and strong stock market gains. As some of these extraordinary factors fade, the Index will most likely return to fluctuating between 40 percent and 50 percent.

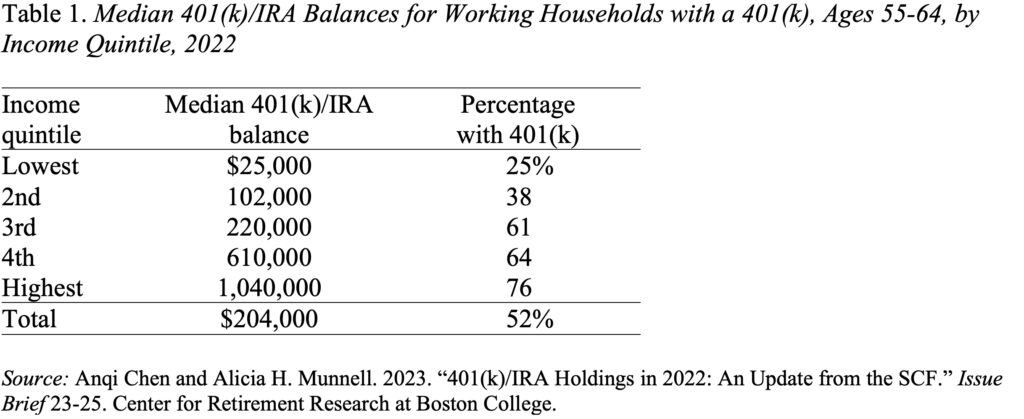

Reinforcing the notion that roughly half of households are at risk is the fact that only half of working households ages 55-64 have any 401(k)/IRA saving. Yes, some have defined benefit plans, but most with defined benefit plans also have a 401(k). Moreover, the amounts in 401(k)s/IRAs are quite modest, except for the top quintile of the income distribution (see Table 1). If the couple in the middle quintile uses their $220,000 to buy a joint-and-survivor annuity, they will receive about $1,200 per month. Since this amount is not indexed for inflation, its purchasing power will decline over time. Moreover, this $1,200 is likely to be the only source of additional income, because the typical household holds virtually no financial assets outside of its 401(k).

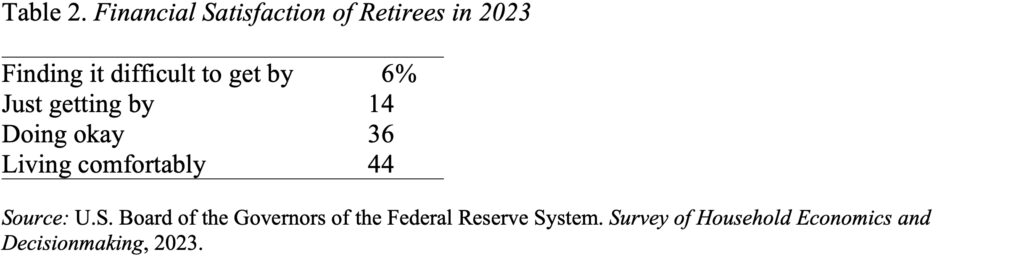

Despite the evidence to the contrary, when older households are asked about how they are faring, the overwhelming majority – 80 percent – say they have enough money to be doing okay or living comfortably (see Table 2). Some interpret the high satisfaction levels as evidence that retirement savings are adequate. My guess has always been that older people are reluctant to say they are doing poorly and just adjust to their financial situation, whatever it is.

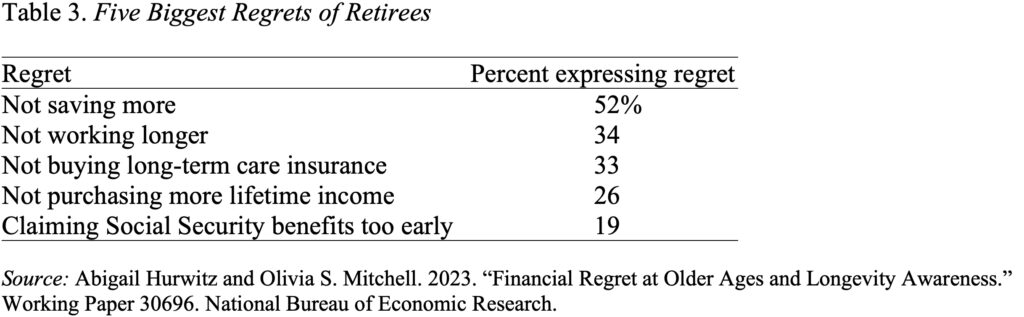

Some evidence that people are putting on a good face when asked about their well-being comes from a recent study of regrets. Actually, the authors deliberately avoided the term ‘regret” and rather asked: “Thinking about your saving over your life: do you think what you saved was too little, about right, or too much?” The results showed that 52 percent felt that they had saved too little. The most common reasons for insufficient saving were that they lived day to day (29 percent) and didn’t plan ahead (27 percent). The other areas of regret are also interesting (see Table 3).

The bottom line here is that all the objective evidence indicates that between 40 and 50 percent are not saving enough and, when the question is put to retirees in a non-threatening fashion, about half admit they wished they had saved more. So, yes, undersaving for retirement is a serious issue.