Does Remote Work Help Older People with Disabilities?

The brief’s key findings are:

- The employment rate for workers ages 51-64 with a disability is significantly above the pre-COVID level.

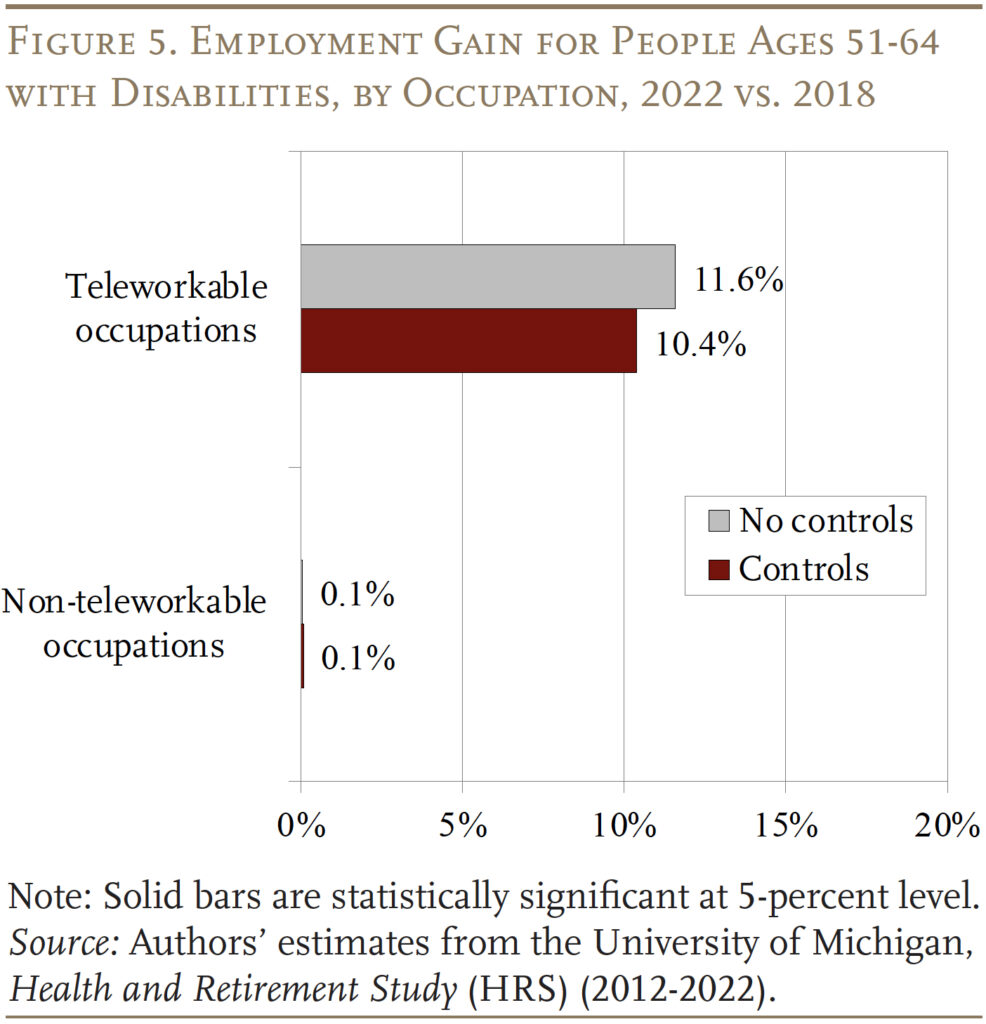

- Nearly all of the employment gain was in teleworkable jobs, even after accounting for other factors that might affect work activity.

- The availability of teleworkable jobs encouraged some to reenter the labor force and others to switch to remote jobs instead of exiting the labor force.

- Whether these effects will persist remains unclear, as remote work options could decline as the labor market returns to more normal conditions.

Introduction

One aspect of the pandemic that has persisted is the increased relevance of remote work. This shift could help older people with disabilities, who might otherwise find it hard to get or keep jobs. Indeed, this group has a higher employment rate post-pandemic than pre-pandemic.

Remote work, though, might not be the only factor contributing to this trend. First, more people report having a work-limiting impairment than before the pandemic. If these new health conditions are relatively mild, then the rising prevalence of disability, by itself, could lead to a higher employment rate among this group. Second, the labor market has been extremely tight in recent years, which could also help boost employment rates among those with disabilities.

This brief, based on a new study, examines the extent to which remote work has contributed to the rising employment rate of older individuals with disabilities and which types of these workers – based on their recent work history – have benefited the most.1 The discussion proceeds as follows. The first section provides background on the rise of remote work, employment trends for older people with disabilities, and the two other factors that could be playing a role: the rising prevalence of disability and the tight labor market. The second section introduces the data and methodology for the analysis. The third section presents the results. The final section concludes that remote work has increased employment among older workers with disabilities by encouraging some to reenter the labor force and others to switch to remote work instead of exiting the labor force.

Background

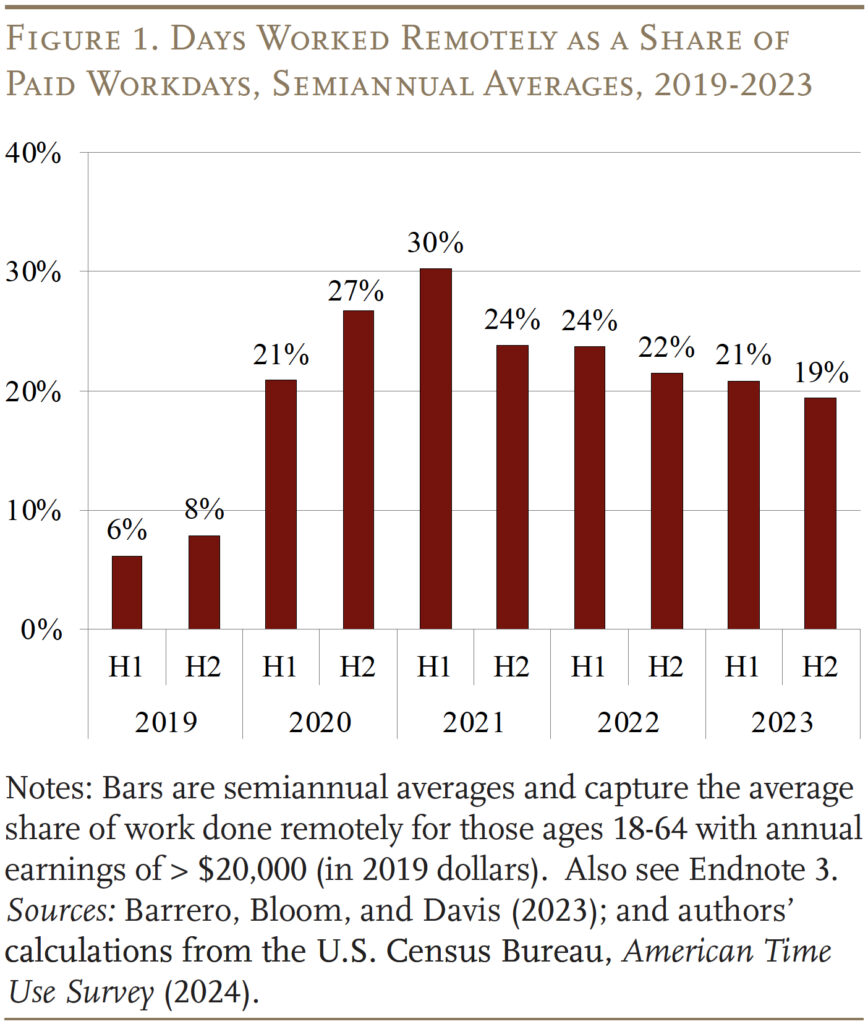

A striking feature of the pandemic was the sudden shift towards remote work, and remote work remains a fixture in the labor market (see Figure 1). For workers with disabilities, remote work lowers the fixed cost of having a job by reducing commuting expenses, providing greater flexibility, and potentially allowing them to access the national labor market.2 For employers, remote jobs can reduce the costs of hiring because required accommodations are already available in the worker’s home.3

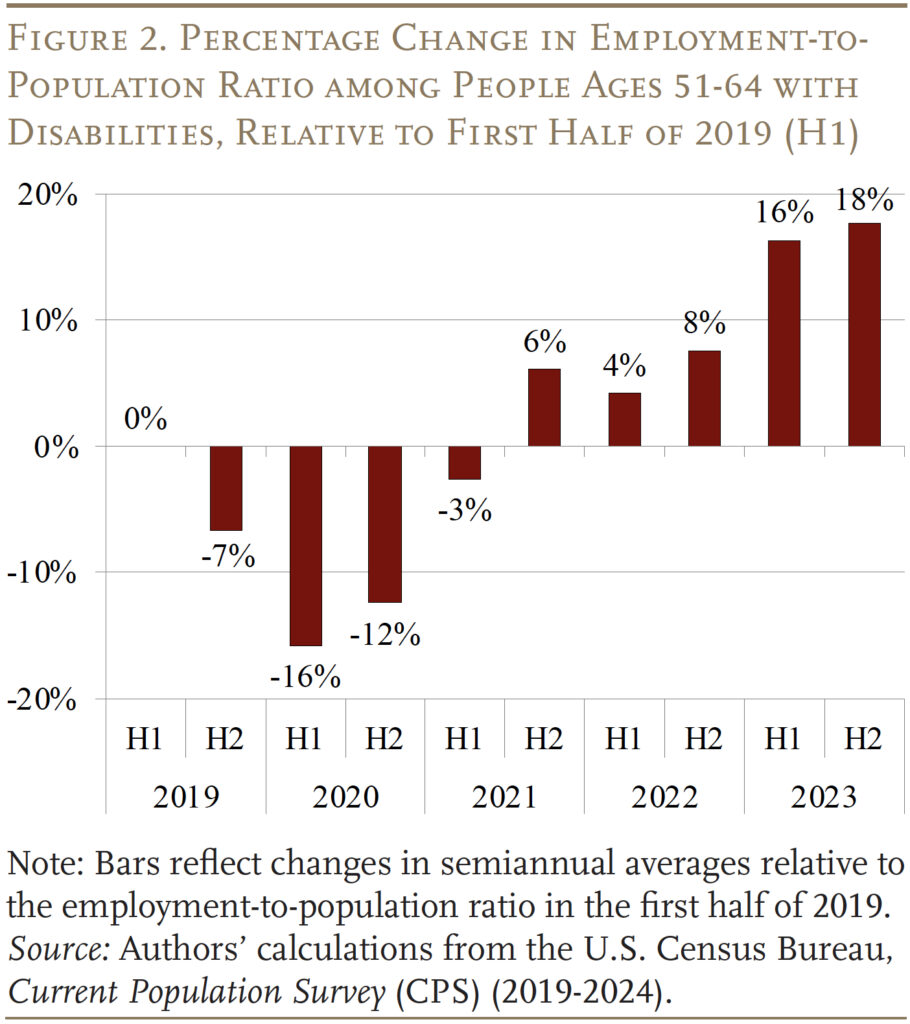

The notion that remote work may be helping older workers with disabilities stay in the labor force is supported by recent employment trends. Figure 2 shows that the employment rate for this group rebounded rapidly after the pandemic, even rising above pre-pandemic levels beginning in late 2021.4

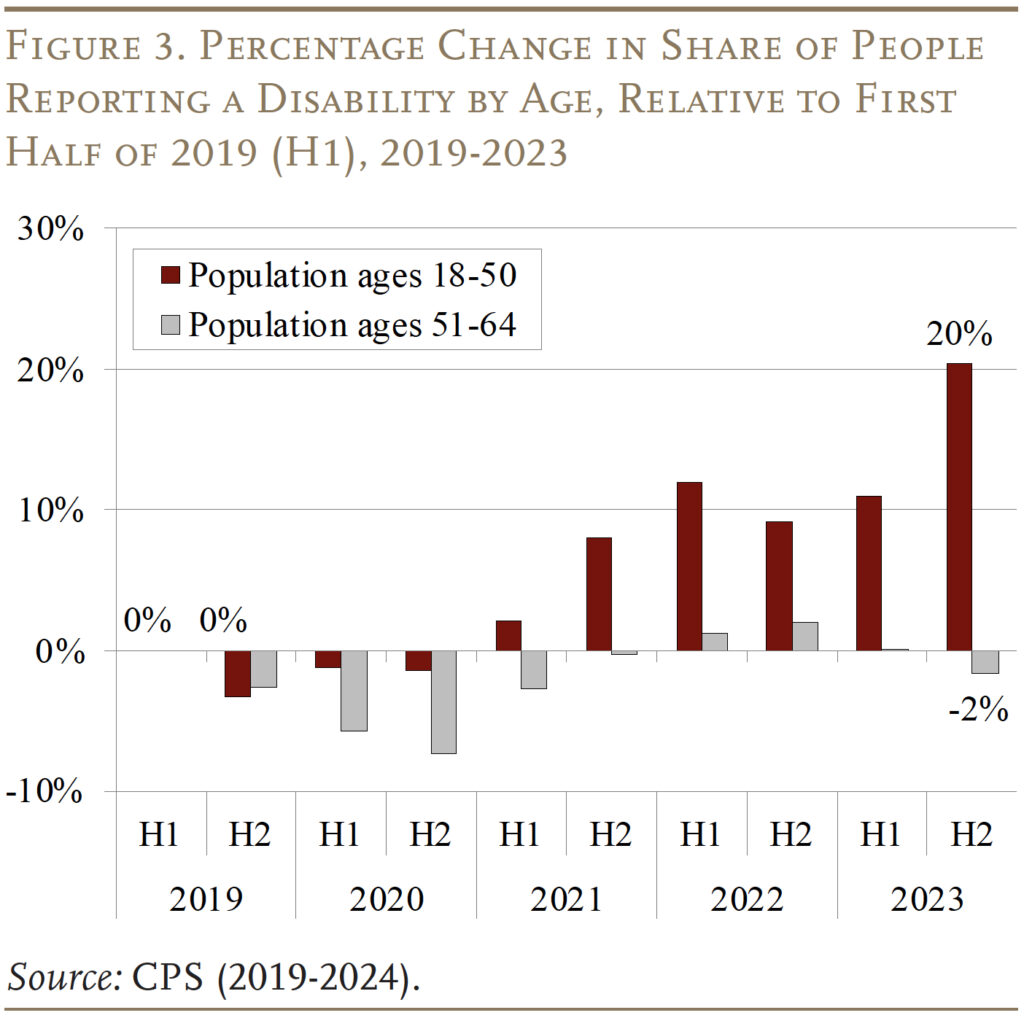

Two other post-pandemic trends, however, could also be influencing employment. First, a higher share of the working-age population now reports having a disability (see Figure 3). Much of this increase can be attributed to a rise in self-reported cognitive impairments. Prior studies suggest that these new impairments might be cases of “brain fog,” a condition related to long COVID.5 If long COVID is the reason, it could result in a shift in the composition of people with disabilities to those with higher work capacity and greater attachment to the labor force.6 Yet, as shown in Figure 3, this argument is less relevant for older workers, since the rise in disability is concentrated among younger workers (ages 18-50).

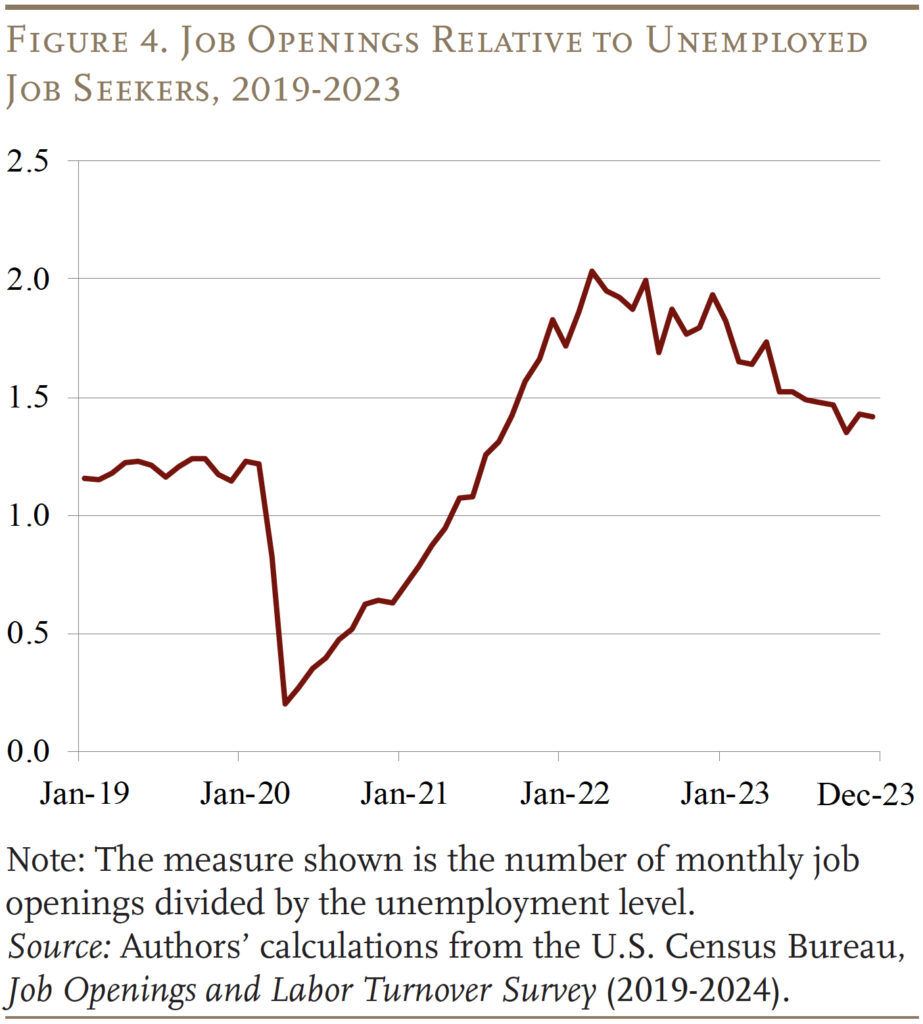

A second, more convincing, factor is the unusual tightness of the labor market in recent years, with the number of job openings rapidly outpacing the number of unemployed job seekers (see Figure 4). As a result, more – and higher-paying – job opportunities have emerged for workers who traditionally face barriers in the labor market.7 In the case of workers with disabilities, employers may be more willing to offer accommodations such as more flexible hours and more frequent breaks.

While labor market tightness appears more likely to affect employment rates among older workers with disabilities than the rising share of adults reporting a disability, the analysis will consider both factors just in case.

Data and Methodology

The analysis is based on the 2012-2022 Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a biennial longitudinal survey of older households with rich information on workers’ health and employment. We focus on individuals ages 51-64 who report a work-limiting health condition and do not consider themselves fully retired.8

The analysis then proceeds in three stages. The first stage simply documents how the rising employment rate for older workers with disabilities breaks down by whether their occupation is amenable to remote work.9 If remote work has had an impact, then we would expect the increase in the employment-to-population ratio of people in teleworkable jobs to be much larger than the increase for those whose jobs are not amenable to remote work.

This simple comparison, however, does not consider the potential effects of other post-pandemic changes. Hence, the second stage estimates the likelihood of older people with disabilities being employed in teleworkable and non-teleworkable occupations, controlling for worker health and the tight labor market, in addition to basic demographics, using the following equation:10

Employment in teleworkable (nonteleworkable) jobs = f(health, labor market tightness, demographics, year 2022)

The year 2022 variable captures the change in teleworkable (non-teleworkable) employment in 2022 compared to 2018 – the omitted reference year. If remote work has an important effect on the employment rate – after accounting for worker health and labor market tightness – then the coefficient on year 2022 should be much larger in the regression for teleworkable jobs than in the non-teleworkable regression.

The final stage of the analysis explores more specifically how remote work helps older workers with disabilities stay in the labor force based on their recent work history, including their experience with teleworkable jobs. Specifically, it asks two questions: 1) did remote work convince those on the sidelines to reenter work, or did it help those who were already working to delay exiting the labor force? and 2) was the impact limited to those who had prior experience with remote work, or did all workers benefit? To answer these questions, the regression analysis outlined above is repeated for subgroups of older people with disabilities based on whether they have worked in the past four years and whether they have had prior experience in a teleworkable job.11

Results

This section starts by examining how remote work improved overall employment for older people with disabilities and then identifies which types of these workers saw the greatest gains.

How Did Remote Work Affect Older People with Disabilities?

To start off, the analysis simply breaks down the increase in the employment rate by whether the worker’s occupation is teleworkable, without controlling for disability severity or labor market tightness. Consistent with the CPS data in Figure 2, the rising employment in teleworkable occupations led to an 11.6-percent increase in the employment-to-population ratio of older people with disabilities between 2018 and 2022, while non-teleworkable employment was virtually unchanged (see gray bars in Figure 5).12

Shifting away from the raw comparisons, the regression results show that remote work remains extremely important even after controlling for disability severity and labor market tightness (see top red bar in Figure 5).13 Indeed, the point estimates barely change from the basic comparison, suggesting that the two potentially confounding factors have played a less important role in increasing employment for older people with disabilities.14

Who Benefited the Most from Remote Work?

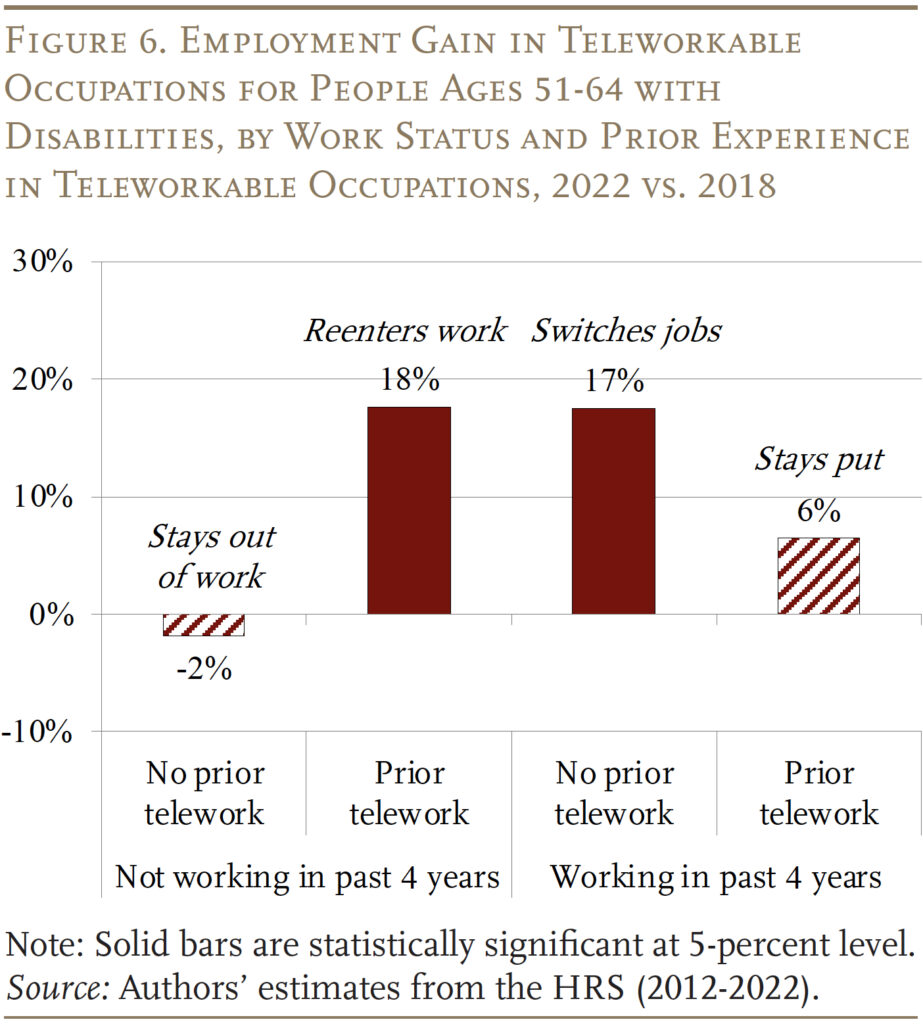

Given that remote work has helped boost employment outcomes for older workers with disabilities, the next question is whether some of them benefited more than others. Figure 6 compares the percentage change in the employment rate for teleworkable occupations across four different groups of older workers with disabilities. These groups are determined based on two aspects of their recent work history. The first aspect is whether or not they were employed in the last four years, while the second is whether or not they had prior experience in teleworkable jobs.

To understand the story, take each result in turn. The first group – those who have not worked in the past four years and have no experience in teleworkable jobs – saw no improvement: they stayed out of work. In contrast, the second group – who do have experience in teleworkable jobs – saw a large increase in employment, indicating that they were better prepared to reenter work as remote jobs surged. The third group is perhaps most interesting. Workers in this group have been employed recently and, despite their lack of familiarity with telework, were able to move into these jobs rather than exiting the labor force because of their disability. Finally, the fourth group – recently working in teleworkable jobs – saw less benefit from the shift to remote work, perhaps because they had already received employer accommodations prior to the pandemic, including the ability to telework.

Conclusion

The shift to remote work that started during COVID and has persisted may have improved job prospects for older people with disabilities by reducing barriers to employment. Consistent with this view, this brief finds that nearly all of the post-pandemic employment gain for older people with disabilities has been in teleworkable occupations, and this pattern holds even after controlling for other factors. Remote work benefits older workers with disabilities by allowing some to reenter the labor force and others to switch jobs instead of exiting work.

Yet, the extent to which these dynamics will persist over the long run remains an open question. This analysis covers a period when remote work was particularly widespread. The availability of remote work may decline as the labor market eases back toward more normal conditions. And, the extent to which older workers with disabilities need or want to work might also decline as the impact of unusual pandemic-era conditions – including the temporary closure of Social Security field offices – subsides. Hence, how remote work impacts older people with disabilities should remain a topic of interest.

References

Barrero, Jose Maria, Nicholas Bloom, and Steven J. Davis. 2023. “The Evolution of Work from Home.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 37(4): 23-49.

Davis, Owen F., Laura D. Quinby, Matthew S. Rutledge, and Gal Wettstein. 2023. “How Did COVID-19 Affect the Labor Force Participation of Older Workers in the First Year of the Pandemic?” Journal of Pension Economics and Finance 22(4): 509-523.

Deitz, Richard. 2022. “Long COVID Appears to Have Led to a Surge of the Disabled in the Workplace.” Liberty Street Economics. New York, NY: Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Dingel, Jonathan I. and Brent Neiman. 2020. “How Many Jobs Can Be Done at Home?” Journal of Public Economics 189: 104235.

Domash, Alex and Lawrence H. Summers. 2022. “How Tight Are US Labor Markets?” Working Paper No. 29739. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Gascon, Charles S. and Samuel Moore. 2024. “Are Workers with a Disability Facing New Opportunities or New Challenges?” On the Economy Blog. St. Louis, MO: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

Guo, Angela and Pawel M. Krolikowski. 2024. “Disability, Immigration, and Postpandemic Labor Supply.” Economic Commentary 2024-05. Cleveland, OH: Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland.

Liu, Siyan and Laura D. Quinby. 2024. “Has Remote Work Improved Employment Outcomes for Older People with Disabilities?” Working Paper 2024-12. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Marks, Cassandra and Hannah Rubinton. 2024. “The Labor Effects of Work from Home on Workers with a Disability.” On the Economy Blog. St. Louis, MO: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

Ne’eman, Ari and Nicole Maestas. 2023. “How Has COVID-19 Impacted Disability Employment?” Disability and Health Journal 16(2): 101429.

O’Trakoun, John. 2024. “Uncertain Outlook for Disabled Employment.” Macro Minute. Richmond, VA: Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

University of Michigan. Health and Retirement Study, 2012-2022. Ann Arbor, MI.

U.S. Census Bureau. American Time Use Survey, 2024. Washington, DC.

U.S. Census Bureau. Current Population Survey, 2019-2024. Washington, DC.

U.S. Census Bureau. Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, 2019-2024. Washington, DC.

Endnotes

- Liu and Quinby (2024). ↩︎

- Ne’eman and Maestas (2023); Barrero, Bloom, and Davis (2023); Marks and Rubinton (2024); and O’Trakoun (2024). ↩︎

- Paid workdays are days where the respondent works six or more hours in their main job. Paid workdays are done remotely if the respondent works six or more hours at home. ↩︎

- Interestingly, the upward trend contrasts with that for older people without disabilities, who experienced slightly decreasing employment rates due to early retirement; see Davis et al. (2023). ↩︎

- Ne’eman and Maestas (2023); Deitz (2022); and Guo and Krolikowski (2024). ↩︎

- Under this hypothesis, the employment gain for people with disabilities is merely mechanical and does not reflect improved job prospects. ↩︎

- Domash and Summers (2022). ↩︎

- Retirees who have not worked in the last four years are excluded because the 2022 HRS does not ask them about work-limiting disabilities. Additionally, respondents in the sample have at least three consecutive interviews. ↩︎

- We use the 2018 and 2022 waves of the HRS to compare outcomes before and after the pandemic. Most respondents in the 2020 wave (the height of the pandemic) reported a large drop in employment followed by a quick recovery. Occupations are classified as “teleworkable” if the share of jobs in that occupation that can be done remotely exceeds 28 percent according to Dingel and Neiman (2021). ↩︎

- Controls for worker health include major health conditions and difficulties with Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) or Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADLs). Labor market tightness is a monthly measure of the number of job openings relative to job seekers at the industry level. The regression also includes interactions of labor market tightness and the respondent’s career job industry, as well as indicators for employment status two and four years ago. To improve the precision of our estimates for the labor market tightness and demographic control variables, the regression sample also includes individuals without a work-limiting condition and extends back to 2012. ↩︎

- We consider an individual to have experience in teleworkable jobs if one of the following is true: 1) their career job is teleworkable; 2) their longest held job after age 50 is teleworkable; or 3) they worked in a teleworkable job within the last four years. ↩︎

- The overall change in the employment rate – 11.6 percent – is slightly higher than changes in the calendar year of 2022 in Figure 2 due to the 2022 wave of the HRS taking place in both 2022 and 2023. ↩︎

- The regression-adjusted employment rate for older people with disabilities is 59 percent in 2018. Interestingly, older people without disabilities have not benefited from the rise of remote work in a similar fashion. Small increases in teleworkable employment correspond to less than 1 percent of the total employment rate, while non-teleworkable employment has dropped for older people without disabilities between 2018 and 2022. Similarly, Gascon and Moore (2024) find that the employment-to-population ratio among working-age people without disabilities has not fully returned to pre-pandemic levels as of 2024. ↩︎

- Supporting this interpretation, we do not find a shift towards individuals with relatively mild impairments among older people with disabilities. And despite recent loosening of the labor market this year, the employment rate for older people with disabilities remains at 2023 levels. ↩︎