More Older Workers with Disabilities Are Finally Getting Hired. Thank Remote Work

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Job prospects have improved since the pandemic for these often overlooked workers.

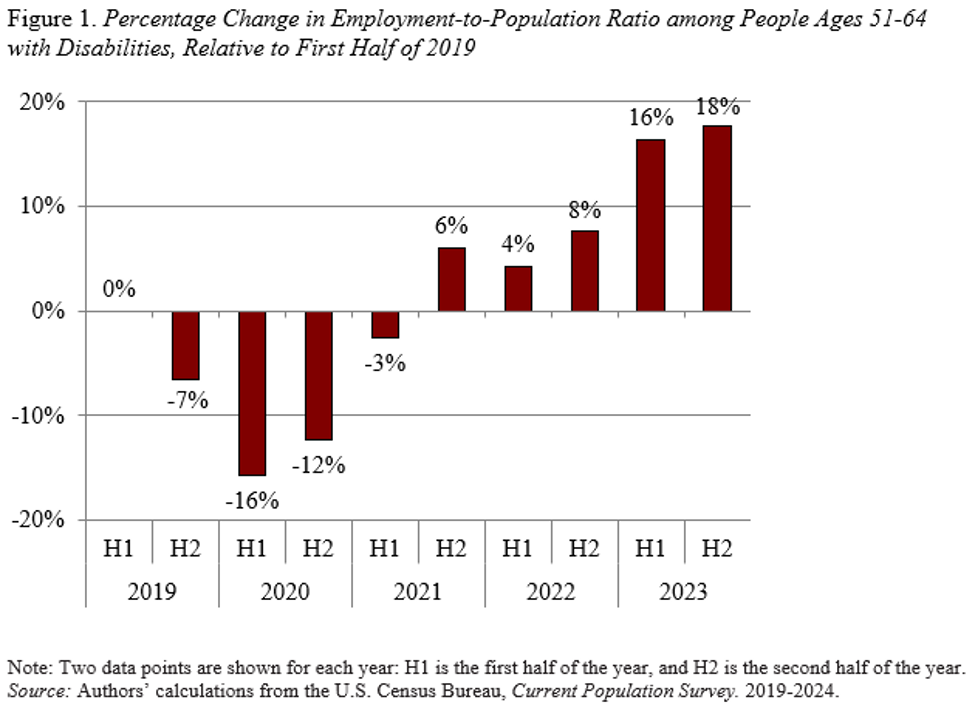

My colleagues just completed an interesting study exploring why the employment rate for older workers with disabilities surged after the pandemic (see Figure 1).

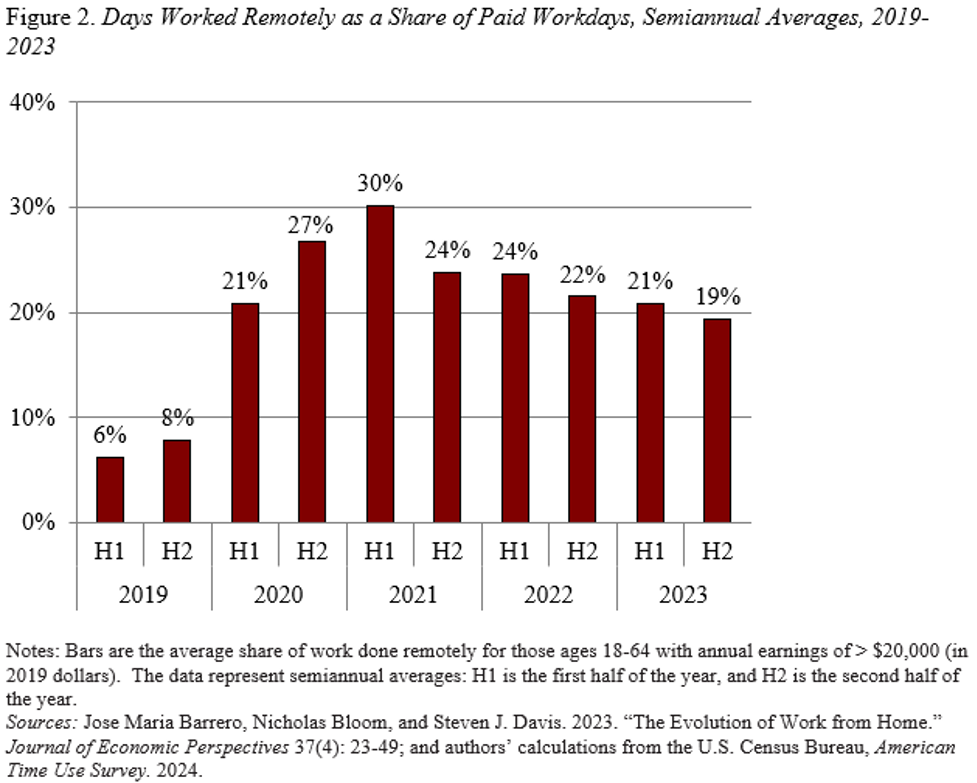

Specifically, they were interested in the extent to which this surge can be attributed to the opportunity to work remotely, which remains way above pre-pandemic levels (see Figure 2).

Answering the question is complicated slightly by the fact that two other post-pandemic trends could also be influencing employment. First, a higher share of the working-age population now reports having a disability, which means that the composition of people with disabilities may have shifted to those with higher work capacity. This argument is less relevant for older workers, however, since the rise in disability is concentrated among younger workers.

A second, more universal, factor is the unusual tightness of the labor market in recent years, with the number of job openings rapidly outpacing the number of unemployed job seekers. As a result, more – and higher-paying – job opportunities have emerged for workers who traditionally face barriers in the labor market. In the case of workers with disabilities, employers may be more willing to offer accommodations such as more flexible hours and more frequent breaks.

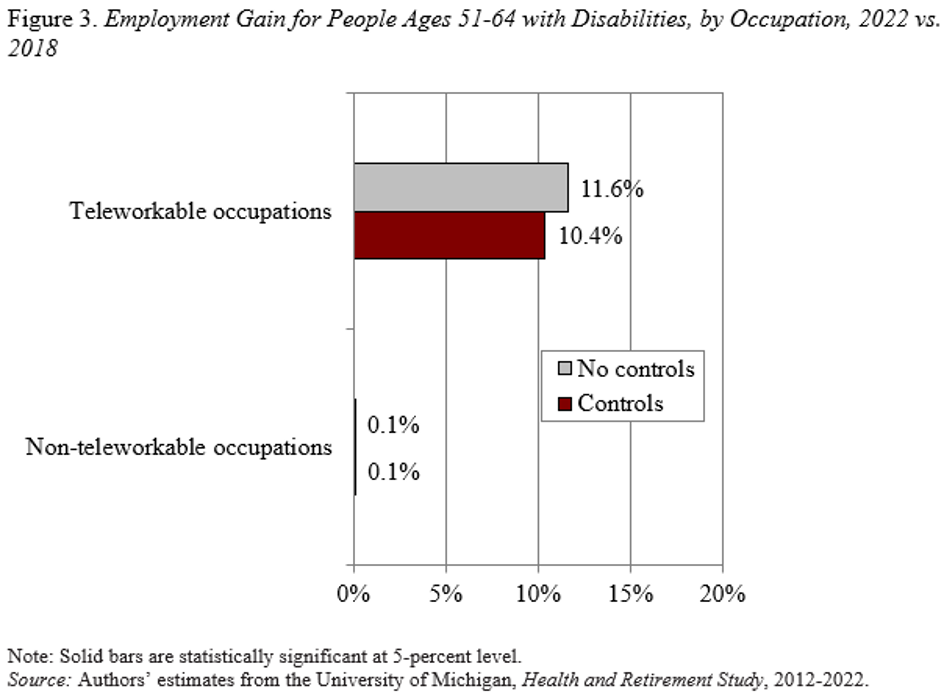

The analysis begins by simply breaking down the increase in the employment rate by whether the worker’s occupation is one where work can be done remotely – that is, the occupation is “teleworkable.” The results show that all the increase in the employment-to-population ratio among older people with disabilities between 2018 and 2022 occurred in teleworkable occupations; no growth occurred in non-teleworkable employment (see gray bars in Figure 3).

These results hold even after controlling for disability severity and labor market tightness (see red bars).

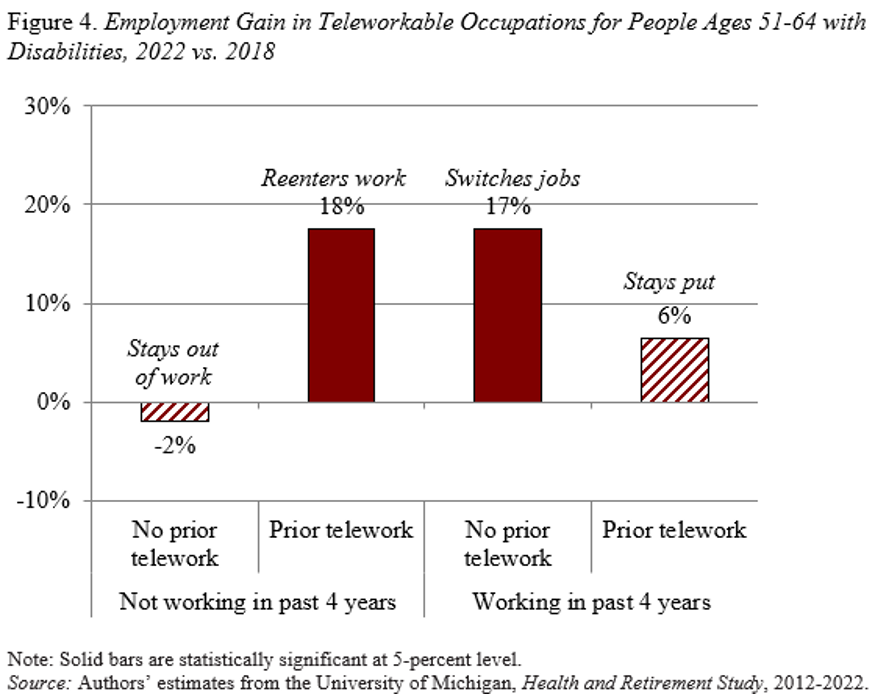

The authors went on to identify the type of workers who gained from the availability of remote work. The workers were grouped by two aspects of their recent work history. The first is whether or not they were employed in the last four years, and the second is whether or not they had prior experience in teleworkable jobs (see Figure 4).

To understand the story, take each result in turn. The first group – those who had not worked in the past four years and had no experience in teleworkable jobs – saw no improvement: they stayed out of work. In contrast, the second group – who did have experience in teleworkable jobs – saw a large increase in employment, indicating that they were better prepared to reenter work as remote jobs surged. The third group is perhaps most interesting. Workers in this group had been employed recently and, despite their lack of familiarity with telework, were able to move into these jobs rather than exiting the labor force because of their disability. Finally, the fourth group – recently working in teleworkable jobs – saw less benefit from the shift to remote work, perhaps because they had already received employer accommodations prior to the pandemic, including the ability to telework.

While the results are persuasive, the extent to which these dynamics will persist over the long run remains an open question. The availability of remote work may decline as the labor market eases back toward more normal conditions. And, the extent to which older workers with disabilities need or want to work might also decline as the impact of unusual pandemic-era conditions – including the temporary closure of Social Security field offices – subsides. We’ll see.