Who Claims Social Security While They Are Still Working – and Why Do They Do It?

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Social Security was originally intended for retirement.

Many older people, however, report receiving both wages and Social Security benefits. That pattern is surprising given the enormous advantage of claiming as late as possible – monthly benefits claimed at age 70 are 76 percent higher than those claimed at 62 – and the fact that the earnings test for those under the Full Retirement Age (FRA) temporarily withholds a portion of benefits.

How many people are both working and claiming benefits? And why are they doing it? To answer these questions, my colleagues Siyan Liu and Laura Quinby used the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a survey that interviews a sample of households every two years and contains detailed information on Social Security claiming, employment, and income. Using HRS data from 1992-2022, they followed individuals at two-year intervals from age 56 – when the vast majority are still in the labor force – to age 75, when most have fully retired.

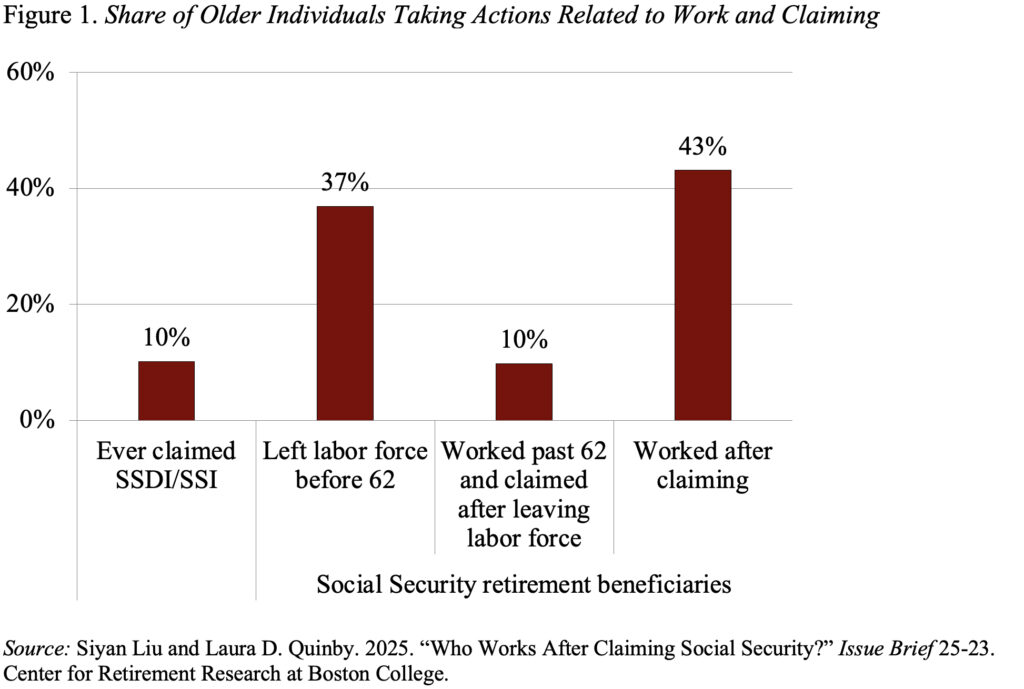

The results show that working after claiming Social Security is quite common – 43 percent of individuals interviewed between ages 56-75 combined work and benefits for at least some period of time (see Figure 1).

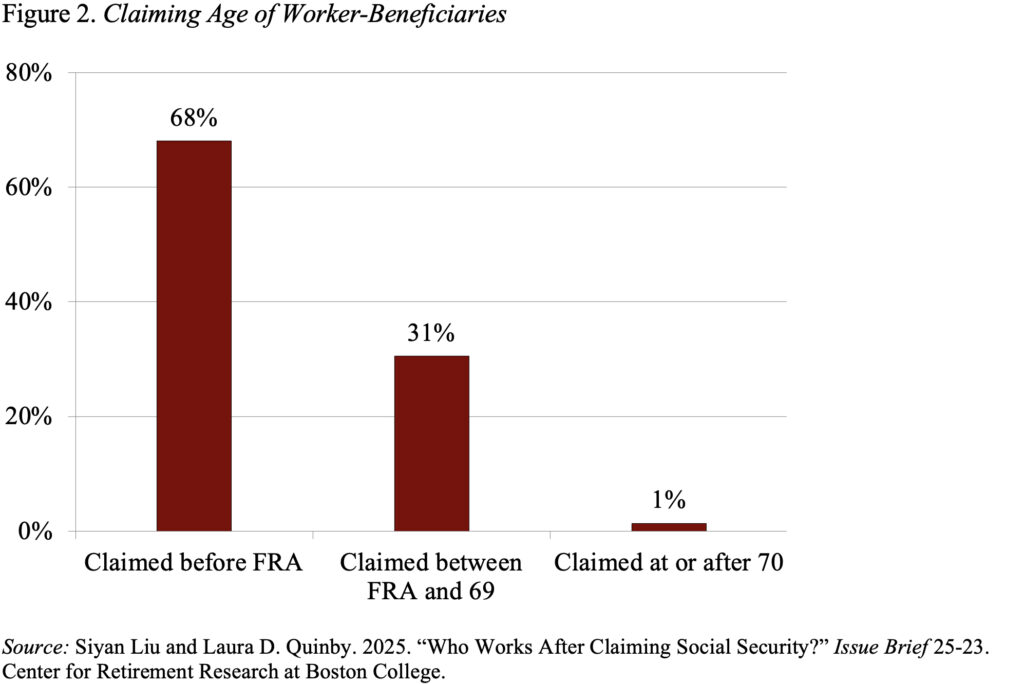

Who are these people? To get some insights, the authors focused on the claiming age of these worker-beneficiary individuals. As shown in Figure 2, two-thirds of them claimed before the FRA – typically right at age 62 – while another 30 percent claimed between the FRA and age 69 – typically right at the FRA. This pattern suggests different circumstances and different reasons for claiming.

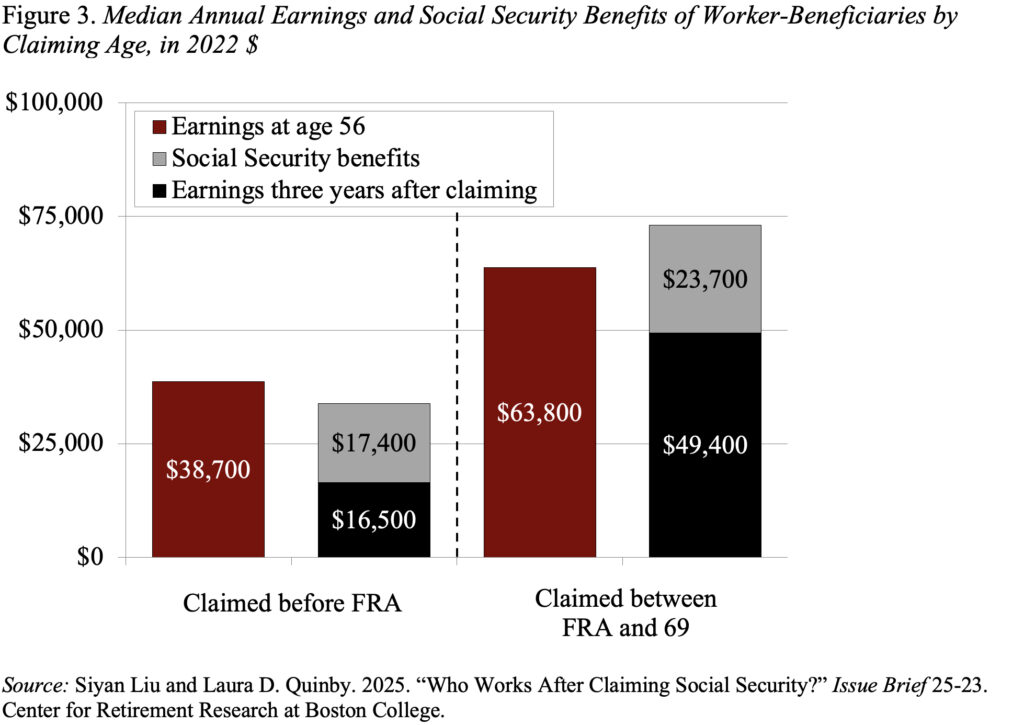

Those who claimed early likely did so because they could not, or chose not to, continue working full-time and needed Social Security benefits to cover their expenses. Indeed, this group was less likely than the late claimers to be college-educated and more likely to work part-time. Moreover, worker-beneficiaries who claimed early typically had lower pre-claiming earnings than late claimers and experienced a big drop in income when they stopped working full-time. Specifically, their median earnings decreased by almost half from $38,700 to $16,500 when they stopped working full-time, and even with Social Security they could not fully offset the gap (see Figure 3).

The pattern of those who claimed after the FRA is harder to understand. Their earnings seem to provide almost as much money as they were receiving when they were working. Therefore, they seem well-positioned to postpone claiming until age 70, when they would have received their maximum monthly benefits. Yet, they chose to claim earlier. Part of the explanation may be that the award for claiming later – the relatively new delayed retirement credit – only reached the full 8 percent for those born in 1943. If the newness and evolution of the delayed retirement credit is the explanation, one would expect to see more delayed claiming to age 70 among the more affluent older workers going forward.

The more important implication from this study, however, is that the majority of worker-beneficiaries are low earners who need their Social Security benefits to pay the bills.