Are Teachers Overpaid or Underpaid?

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

New study shows total compensation comparable to other college educated workers.

Whether public employees are over- or under-paid relative to their private sector counterparts is a source of lively debate. Much of the research on the relative compensation of public and private workers has focused on teachers – the largest segment of the public workforce. Moreover, the issue of teacher compensation has gained currency since the Great Recession, as states and school districts have frequently faced tough budget decisions to cut benefits or halt pay raises. And teacher compensation has important implications for hiring and retaining high-quality teachers and, consequently, for student academic performance.

An extensive literature that compares the wages of public school teachers to that of other college educated individuals generally finds that teachers earn significantly lower wages than their private sector counterparts.

But public sector workers tend to receive a larger portion of their compensation in the form of benefits than private sector workers. As such, any gap in wages for teachers may be partially – or completely – offset by more generous benefits.

Previous studies measuring total compensation have tended to use broad averages for the health and retirement costs, which wash over meaningful differences among workers by region, employer size, and occupation. And they fail to fully explain the role of all other benefits, including Social Security, supplemental pay, and paid leave, which turn out to be important.

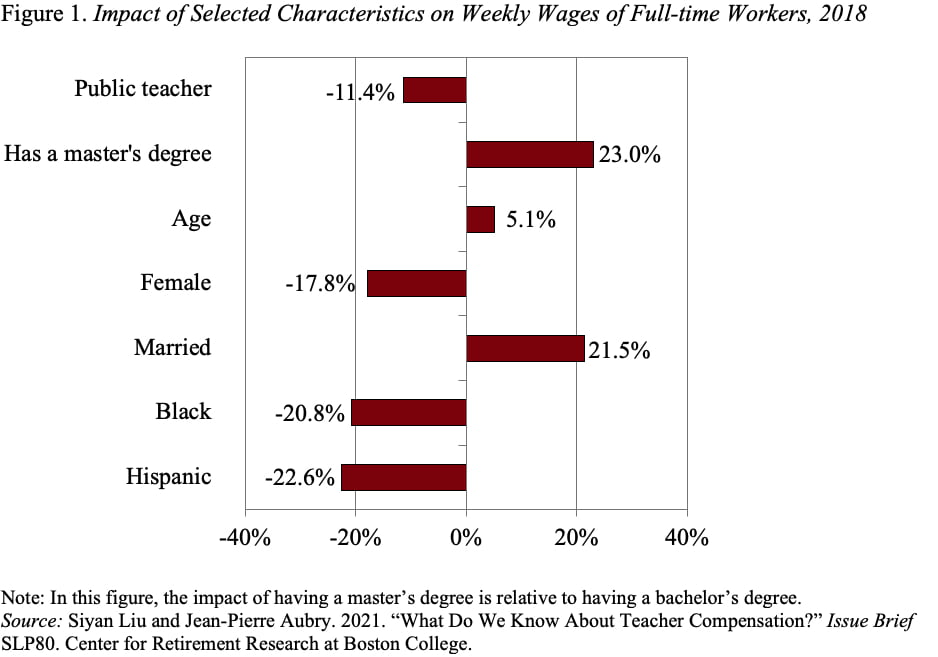

To move the ball forward, my colleagues Siyan Liu and JP Aubry have just completed a comprehensive assessment of teacher compensation. They start with a standard regression relating wages to a bunch of demographic variables, educational attainment, and whether the individual is a public school teacher. The results show that teachers earn – on average – about 11 percent less in wages (see Figure 1).

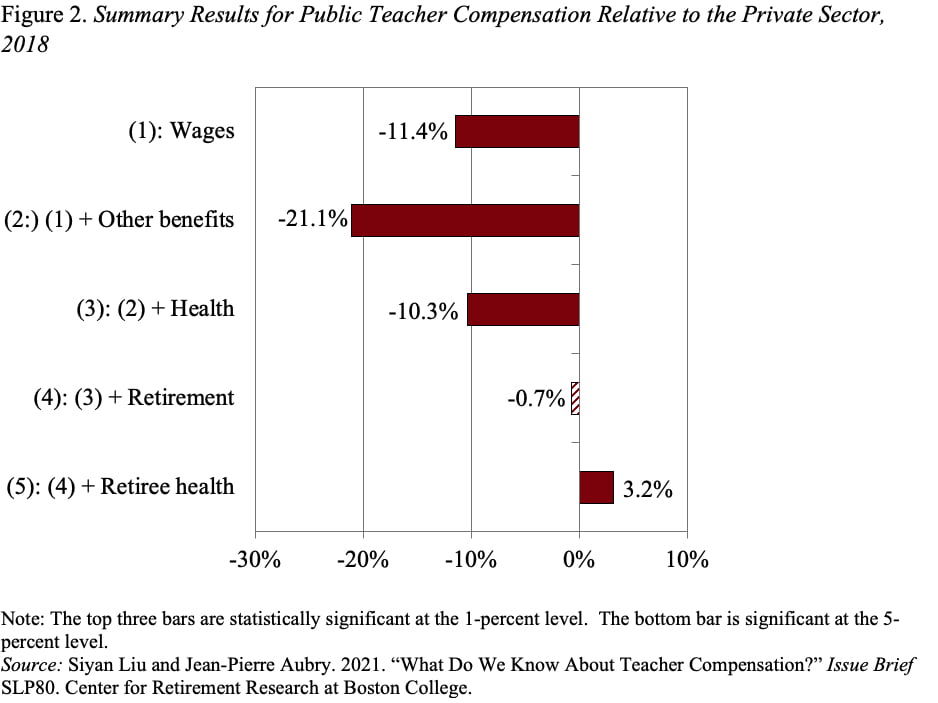

Wages, however, are only part of the story. A complete picture of compensation requires adding the value of health insurance, retirement benefits, retiree health insurance, and other benefits to the wages of each teacher and private sector worker. In all cases, each public and private worker is matched – based on location and firm size – to the relevant retirement plan or benefit measure. This matching exercise finds that teachers get much more in retirement and health care, but less in other benefits like bonuses and paid leave.

Liu and Aubry then re-run their initial wage regression with “wages plus benefits” as the dependent variable. Figure 2 shows the estimated differential between teachers and private sector workers at four different stages: 1) wages only; 2) wages plus “other” benefits; 3) wages, other, and employee health care; 4) wages, other, employee health, and retirement; and 5) wages, other, employee health, retirement, and retiree health.

The authors conclude that – with only a 3.2-percent differential – teachers currently earn roughly the same as similar private sector workers in other professions. But, given the benefit cuts in state and local retirement plans, average compensation for teachers is likely to worsen as newer teachers hired after the Great Recession form the majority of the teaching workforce. Uncompetitive compensation may make it harder to recruit high-quality individuals into the teaching profession – potentially leading to worse outcomes for students.