What Matters for Annuity Demand: Objective Life Expectancy or Subjective Survival Pessimism?

The brief’s key findings are:

- Few people buy annuities, which has long puzzled researchers.

- This study assesses the relative importance of two potential reasons for this low demand:

- annuity prices are based on the longer objective life expectancy of those who buy them, making them expensive for others; and

- people in their 50s and 60s are too pessimistic about their life expectancy, so they place a lower value on annuities.

- The results show both factors impact annuity demand, but objective life expectancy has a much larger effect than pessimism.

- The implication is that a larger public role may be required to boost annuitization.

Introduction

Since 1965, academics have argued that individuals should annuitize a large part of their wealth. However, for nearly as long, studies have documented that annuitization rates fall far short of what seem to be optimal levels. Researchers have proposed multiple explanations for this potentially sub-optimal outcome.

This brief, based on a recent study, assesses the relative importance of two explanations of this outcome, called the annuity puzzle.1Arapakis and Wettstein (2023). The first explanation is that annuity prices are set to compensate insurers for the higher average life expectancy of those who voluntarily purchase annuities, thereby making the product less attractive to potential consumers. The second explanation is that individuals in their 50s and 60s subjectively underestimate their life expectancy, which makes them perceive annuities as less attractive.2For an early discussion of the impact of subjective mortality on annuitization decisions, see Hamermesh (1985).

The discussion proceeds as follows. The first section provides a brief background. The second section describes the data and methodology. The third section presents the results: a one-year decrease in objective life expectancy is associated with a 0.20-percentage-point reduction in the chance of receiving income from a commercial annuity, which is nearly nine times larger than the association with an individual subjectively believing that he will live for one year less. The final section concludes that better understanding what drives annuitization is important for annuity providers and policymakers alike. If irrational subjective mortality pessimism were driving low annuitization rates, better informing the public about mortality rates could have reduced the problem. Given that objective life expectancy is the more important factor, a larger public role in the provision of annuities could be considered.

Background

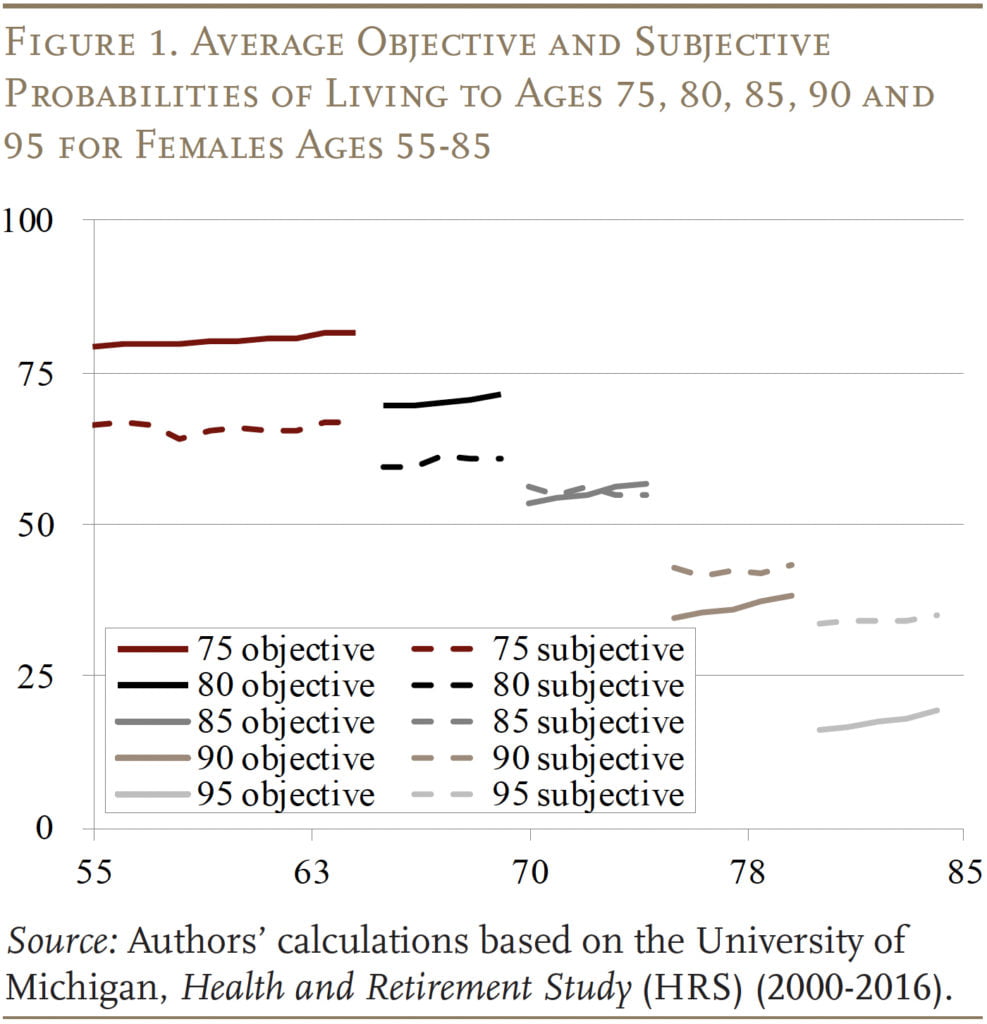

Of the many possible explanations for the annuity puzzle, irrational pessimism about future life expectancy is particularly appealing. Past empirical work has documented that during the ages that individuals are most likely to benefit from buying an annuity, they are subjectively pessimistic about their mortality. This pattern is evident in Figure 1 which shows that women are pessmistic between 55 and their mid-70s (the solid lines are above the dashed lines), but optimistic after that. The pattern is similar for men.

Further, theoretical work has shown that annuitization rates can be substantially depressed in a lifecycle model due to pessimistic survival expectations.3See O’Dea and Sturrock (2021). Prior research has also shown that subjective mortality expectations are relevant to decision-making in several other related contexts, such as timing of retirement and Social Security claiming (Hurd, Smith, and Zissimopoulos 2004 and Bloom et al. 2006) and savings (Post and Hanewald 2013 and Heimer, Myrseth, and Schoenle 2019). However, the impact of such survival pessimism on annuitization after controlling for objective life expectancy has not been empirically demonstrated.

Studying the topic is complicated since subjective mortality pessimism may be correlated with objective life expectancy. Also, individual objective mortality expectations may vary from full-population life tables that differ only by gender and birth year for perfectly rational reasons: information on race, socioeconomic status (SES), and health conditions may reasonably inform individuals’ assessments of their life expectancy above and beyond irrational pessimism. Both low objective-life-expectancy assessments and pessimism may reduce demand for annuities priced for those with high life expectancies. The next sections describe how the analysis distinguishes the objective life expectancy and subjective pessimism of potential annuity consumers.

Data and Methodology

The study draws on data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a nationally representative, biennial longitudinal survey of adults in the United States. The survey started in 1992, with a new cohort ages 51-56 entering every six years. The HRS asks questions about a wide range of topics used in retirement research, including education, income, wealth, health, cognition, expectations, and demographics.

The expectations module of the survey asks participants about their self-reported probability of living to older ages. These questions take the form: “What is the percent chance that you will live to be age [X] or more?” As indicated above, participants answer this question with a number between 0 and 100. We use these answers to estimate individual subjective survival curves and subjective life expectancies.4This procedure follows O’Dea and Sturrock (2021).

To calculate objective life expectancies, the analysis uses the life tables estimated by Wettstein et al. (2021). The tables include mortality rates by gender, cohort, race, age, and education, combining data from the National Vital Statistics System and the American Community Survey.

To assess the relative importance of objective life expectancy and subjective mortality pessimism, we conduct a horse race between the two measures. Using this approach, the analysis can control for the contribution of objective life expectancy to annuity demand and, holding objective life expectancy constant, it can estimate the incremental effect of pessimism. Specifically, we use ordinary least squares and estimate the regression equation:

Annuity Demand = f(Objective LE, Subjective Pessimism, Controls)

where subjective pessimism is defined as the difference between objective and subjective life expectancies. This regression is run with the dependent variable being either the presence of an annuity or the share of financial wealth held in an annuity. If objective life expectancy were important, then we would expect it to have a statistically significant positive coefficient. If subjective pessimism were important, then we would expect a statistically significant negative coefficient on that variable.

Results

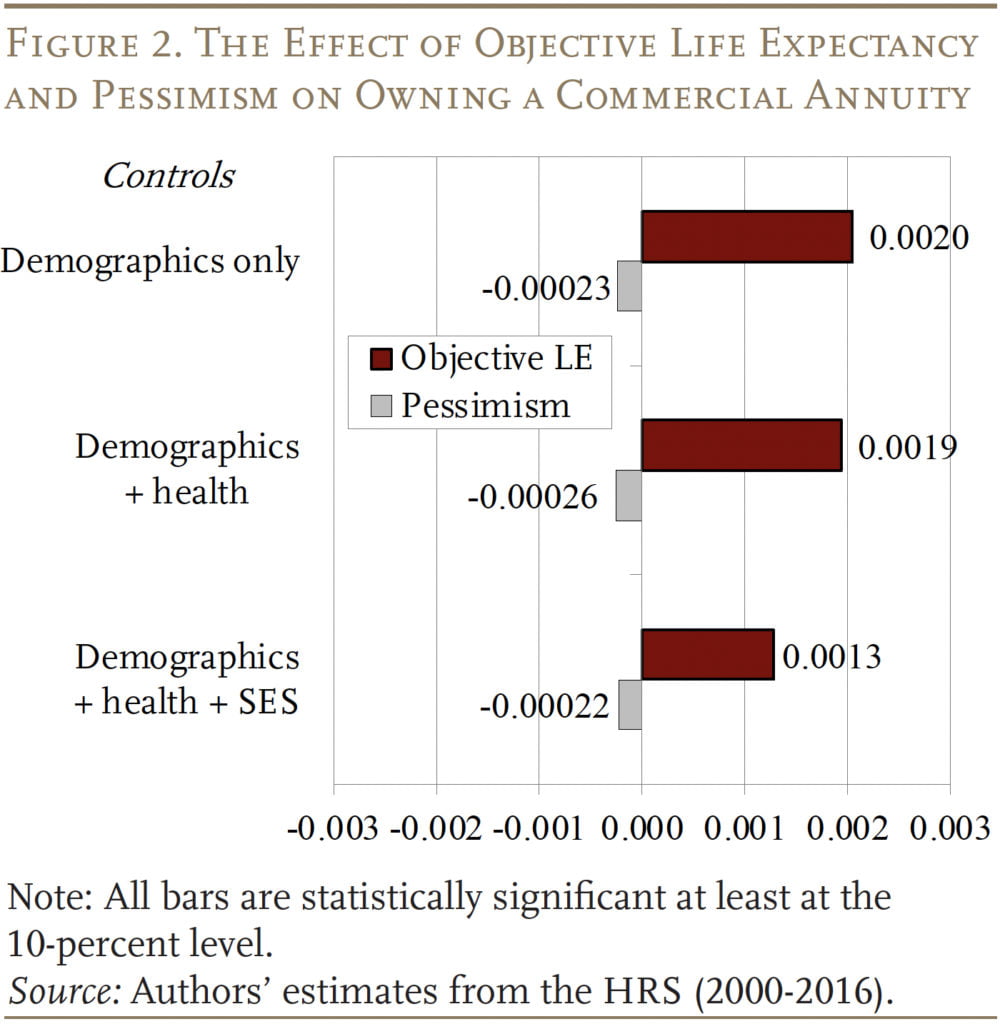

The results, displayed in Figure 2, show that both coefficients for objective life expectancy and pessimism have the expected signs and are statistically significant. This finding implies that both factors affect the choice of whether to purchase an annuity.

The results include three different specifications that vary based on the number of control variables. The results shown in the top cluster of Figure 2 include controls for the information available to a potential insurer (objective life expectancy, gender, and age) and pessimism. By controlling for the information insurers use in pricing annuities, and only that information, these results show the correlation of annuity demand with pessimism holding the price of the annuity constant. Specifically, a one-year increase in objective life expectancy increases the probability of holding an annuity by 0.20 percentage points (for context, the share who ever buy an annuity is 8.8 percent), while a one-year decline in pessimism increases the probability of holding an annuity by 0.023 percentage points.

In the middle cluster of results, additional controls for objective physician-diagnosed health conditions are included. Controlling for health conditions helps make the case that the difference between individuals’ views of their mortality and their objective mortality are not driven by objective factors such as health. The downside of adding these controls is that the measure of pessimism no longer captures pessimism driven by health conditions.5Furthermore, the coefficient on life expectancy can no longer be interpreted as selection, since selection might involve individuals’ private information about their health (which is held constant here).

The bottom cluster includes economic factors that may influence annuity demand on the individual’s part beyond life expectancy, such as marital status, whether the individual has children, and the presence of a defined benefit pension plan (in addition to the health controls). These controls help test whether the estimated effects of objective life expectancy and pessimism are driven by socioeconomic factors that are correlated with annuity demand and life expectancy.

With either set of additional controls, objective life expectancy and pessimism are still statistically significant, although the magnitude and significance of objective life expectancy declines as more controls are added. The results of the three clusters combined imply the following: selection occurs based on both objective life expectancy and pessimism, and this selection does not disappear once we control for health and SES variables.

When we repeat the analysis replacing the dependent variable with the share of financial wealth held in an annuity, in the basic equation, objective life expectancy is marginally significant while pessimism is not. However after adding the controls, the pattern flips: objective life expectancy is no longer significant but pessimism is marginally significant. Given the marginal significance of these results, the evidence on the share of annuitized wealth is inconclusive.6Finding selection in one contract dimension but not in another is not unusual. Finkelstein and Poterba (2004) also find evidence of selection on some contract dimensions, and no evidence on others.

Conclusion

This brief explores the relative importance of objective life expectancy and subjective survival pessimism in annuitization decisions, using regression models that control for these and other characteristics that are linked to annuitization decisions.

Results suggest that both objective life expectancy and subjective pessimism are correlated with the presence of a commercial annuity. However, the estimates indicate that objective life expectancy is more important than pessimism in the decision of whether to annuitize. A one-year increase in objective life expectancy increases the chance of buying a commercial annuity by 0.20 percentage points. Meanwhile, a one-year decline in pessimism is associated with an increase of 0.023 percentage points in the probability of having an annuity, much smaller than the coefficient on objective life expectancy.

Better understanding what drives annuitization is important for annuity providers and policymakers alike. If irrational subjective mortality pessimism were driving low annuitization rates, better informing the public about mortality rates could have reduced the problem. Given that selection appears to be based mostly on objective life expectancy, a larger public role may be required to boost annuitization.

References

Arapakis, Karolos and Gal Wettstein. 2023. “What Matters for Annuity Demand: Objective Life Expectancy or Subjective Survival Pessimism?” Working Paper 2023-2. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Bloom, David E., David Canning, Michael Moore, and Younghwan Song. 2006. “The Effect of Subjective Survival Probabilities on Retirement and Wealth in the United States.” Working Paper 12688. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Finkelstein, Amy and James Poterba. 2004. “Adverse Selection in Insurance Markets: Policyholder Evidence from the U.K. Annuity Market.” Journal of Political Economy 112(1): 183-208.

Hamermesh, Daniel S. 1985. “Expectations, Life Expectancy, and Economic Behavior.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 100(2): 389-408.

Heimer, Rawley Z., Kristian Ove R. Myrseth, and Raphael S. Schoenle. 2019. “YOLO: Mortality Beliefs and Household Finance Puzzles.” The Journal of Finance 74(6): 2957-2996.

Hurd, Michael D., James P. Smith, and Julie M. Zissimopoulos. 2004. “The Effects of Subjective Survival on Retirement and Social Security Claiming.” Journal of Applied Econometrics 19(6): 761-775.

O’Dea, Cormac and David Sturrock. 2021. “Survival Pessimism and the Demand for Annuities.” The Review of Economics and Statistics: 1-53.

Post, Thomas and Katja Hanewald. 2013. “Longevity Risk, Subjective Survival Expectations, and Individual Saving Behavior.” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 86: 200-220.

University of Michigan. Health and Retirement Study, 2000-2016. Ann Arbor, MI.

Wettstein, Gal, Alicia H. Munnell, Wenliang Hou, and Nilufer Gok. 2021. “The Value of Annuities.” Working Paper 2021-5. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Endnotes

- 1Arapakis and Wettstein (2023).

- 2For an early discussion of the impact of subjective mortality on annuitization decisions, see Hamermesh (1985).

- 3See O’Dea and Sturrock (2021). Prior research has also shown that subjective mortality expectations are relevant to decision-making in several other related contexts, such as timing of retirement and Social Security claiming (Hurd, Smith, and Zissimopoulos 2004 and Bloom et al. 2006) and savings (Post and Hanewald 2013 and Heimer, Myrseth, and Schoenle 2019).

- 4This procedure follows O’Dea and Sturrock (2021).

- 5Furthermore, the coefficient on life expectancy can no longer be interpreted as selection, since selection might involve individuals’ private information about their health (which is held constant here).

- 6Finding selection in one contract dimension but not in another is not unusual. Finkelstein and Poterba (2004) also find evidence of selection on some contract dimensions, and no evidence on others.