Do Older Adults Understand Healthcare Risks, and Do Advisors Help?

The brief’s key findings are:

- Uninsured healthcare costs in retirement can be substantial, so older households need a good understanding of the potential risks.

- New survey results show that many underestimate their healthcare needs and know little about the costs of medical or long-term care services.

- In contrast, financial advisors have a better sense of needs and costs, but households with advisors do not seem to know more than those without.

- As a result, many retirees may not protect themselves against health shocks, forcing them to make difficult changes to cover shocks when they do occur.

Introduction

Households approaching retirement face a wide variety of risks to their financial security. They may live longer than planned and deplete their resources; they may experience unexpectedly high inflation; or they may receive unusually poor returns on their investments. Equally consequential is the risk that households will face major expenses to cover medical and long-term care (LTC) costs.

This brief, which is based on a recent paper, investigates how older households and financial advisors perceive medical and LTC risks in retirement, how those perceptions compare to reality in terms of incidence and costs, and how households plan to respond if their resources prove inadequate.1

The discussion proceeds as follows. The first section introduces the two components of medical and LTC risks – individual risk and general price risk – and discusses the extent to which each is covered by insurance. The second section describes a new household survey and compares households’ beliefs to actual experiences from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a large longitudinal survey. The third section, using results from a new advisor survey, explores advisors’ knowledge of medical and LTC risks and their ability to transmit that information to their clients. The fourth section assesses the reasonableness of households’ planned responses should resources prove insufficient. The final section concludes that older households tend to underestimate medical and LTC risks and costs in retirement. Advisors, on the other hand, have a better sense of these risks and costs, but their older clients do not appear to know more than households without advisors.

Healthcare Risks in Retirement

In this brief, we use “healthcare” to refer to any health-related costs, whether they involve periodic medical care or long-term care. Medical and LTC risks have different implications for retirement planning, because they differ in terms of individual risk and general price risk. Individual risk is the likelihood that a retiree will actually face a medical shock or need LTC. General price risk is the likelihood that the rising cost of the services will erode a household’s financial security. The difference between these two components is that individual risk can, theoretically, be insured by risk pooling, while general price risk affects everyone and thus cannot be handled by pooling.

Medical Risks

Medical risks are fundamentally high and uncertain. Fortunately, much of this risk is insured by Medicare (and Medicaid for those eligible for both programs), which limits out-of-pocket payments. That said, for middle-income retirees, medical premiums and copays eat up about one-third of Social Security income and one-fifth of total income.2 The risk that cannot be insured is that of premiums rising. The premiums for Medicare Part B (doctor visits) tend to increase faster than inflation. As a result, while retirees may be moderately well-insured against a large medical expense in a given year, compounding increases of unpredictable size in premiums can erode their disposable income over time.

LTC Risks

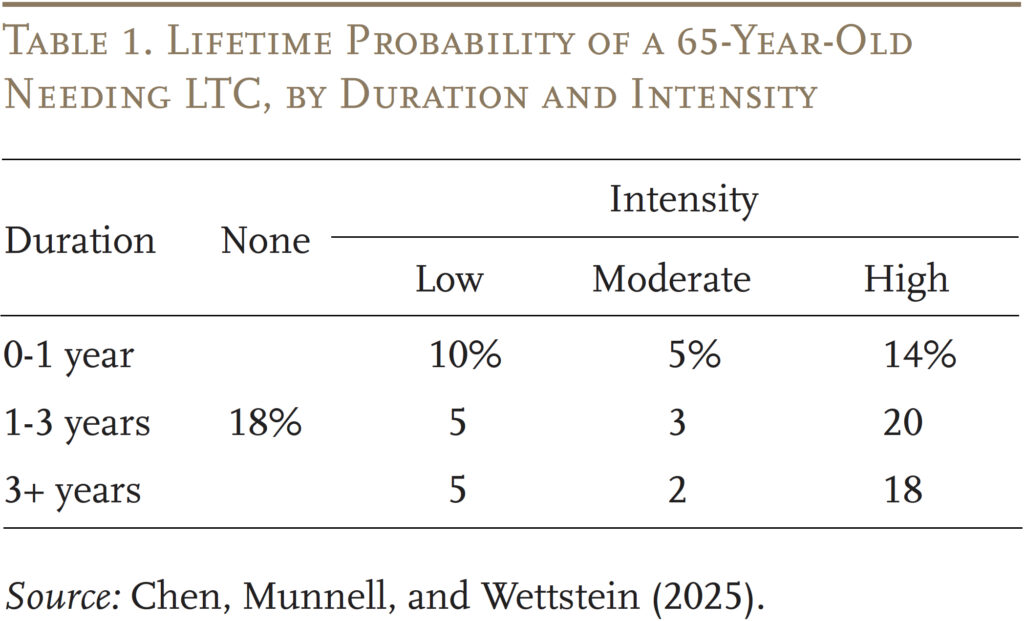

In addition to medical risks, most older adults will have some LTC needs. In fact, only about 20 percent will get by scot-free (see Table 1). However, among the 80 percent who will require some LTC, needs vary dramatically in both intensity and duration. About 40 percent will have high-intensity needs for more than a year.3 Many in this group have Alzheimer’s disease or related dementias – they often need around-the-clock supervision and can live for many years with the disease.

Unlike medical risks, individual LTC risks are not well insured. Despite the high likelihood and cost of LTC, only about 7.5 million people have LTC insurance, representing around 3 percent of all U.S. adults or 15 percent of those ages 65+.4 Medicaid, the public insurance program targeted at low-income individuals, has become a default insurer for catastrophic costs. For middle-income families, however, qualifying for Medicaid would require spending down to meet the program’s stringent income and asset tests.5 In 2024, the monthly income limit for Medicaid eligibility for those over age 65 is typically around $2,800 ($5,600 for couples) and the asset limit is typically $2,000 ($3,000 for couples), but varies by state.

Family members often cover the majority of care hours for people with low and moderate needs and supplement the efforts with paid caregivers as needs increase.6 Historically, women, particularly spouses and daughters, have provided the bulk of family care. Going forward, changes in the labor force participation of women may impact the supply of family caregivers.7

Paid LTC is very expensive – in 2023, the median annual costs were $116,800 for a private room in a nursing home, $75,500 for home health aides, and $64,200 for an assisted living facility.8 The extent of the general price risk households face in the future is unclear. The shortage of qualified workers and growing need for specialized care has driven up the general price of paid LTC.9 Albeit, some studies suggest that the shift from nursing home care to home-and-community-based services in recent decades may help slow the price trends for formal care.10

In short, households face the prospect of large outlays for healthcare costs in retirement. The question is the extent to which households and their advisors perceive these risks and have plans to address them. To answer these questions, the next section turns to the results of two recent surveys conducted by Greenwald Research in July and August of 2024.

Perceptions of Healthcare Risks

For the household survey, Greenwald Research interviewed online 508 individuals ages 48-78 with at least $100,000 in investable assets in July 2024. In the case of married/partnered individuals, the survey participant must at least share financial decision-making responsibilities. The survey asked participants about their perceived likelihood of experiencing a medical shock or needing extensive LTC, as well as the potential cost of these events. The responses were then compared to the actual experiences of older adults in the HRS to determine whether households have a good sense of the likelihood of their shocks and their uninsured risks.

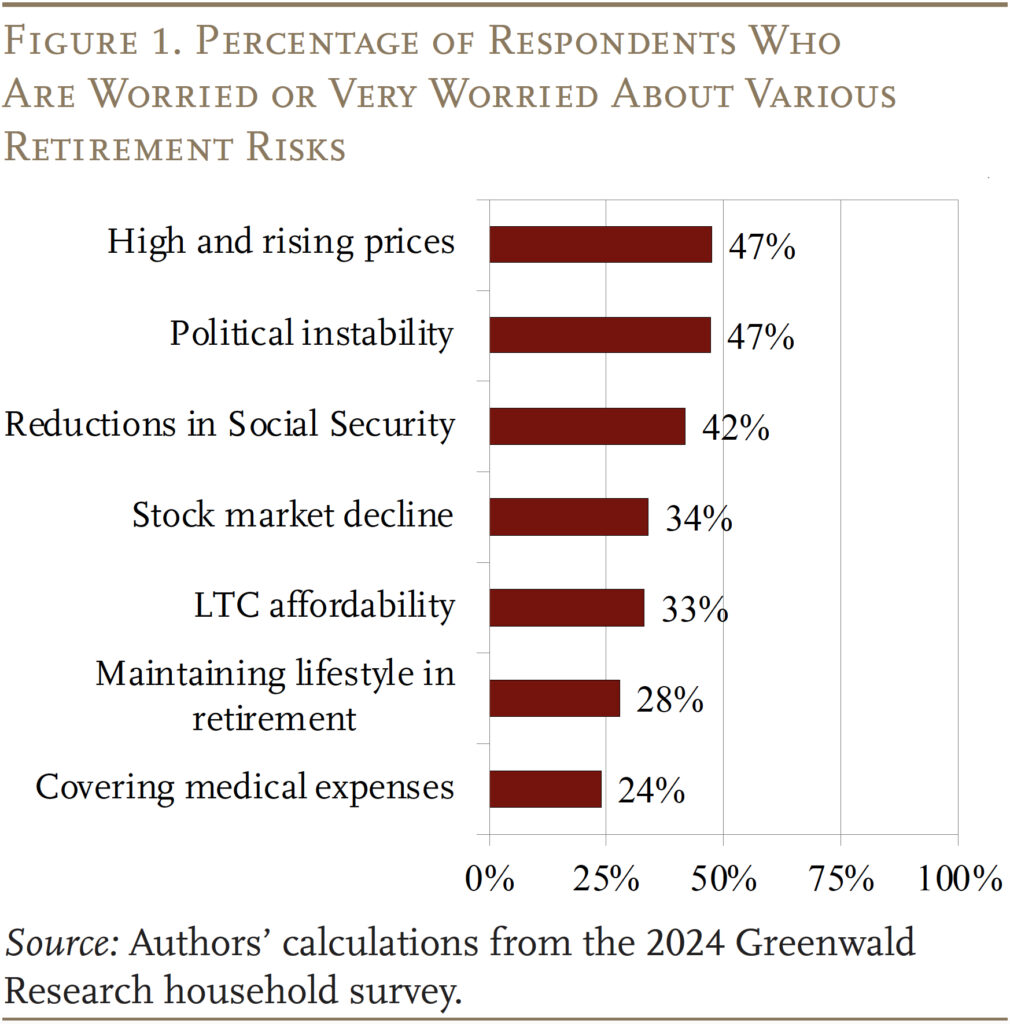

Before looking at the specific responses, it is interesting to note that medical and LTC needs were low on most respondents’ list of concerns (see Figure 1). This finding is consistent with other studies showing older households rank healthcare worries quite low.11

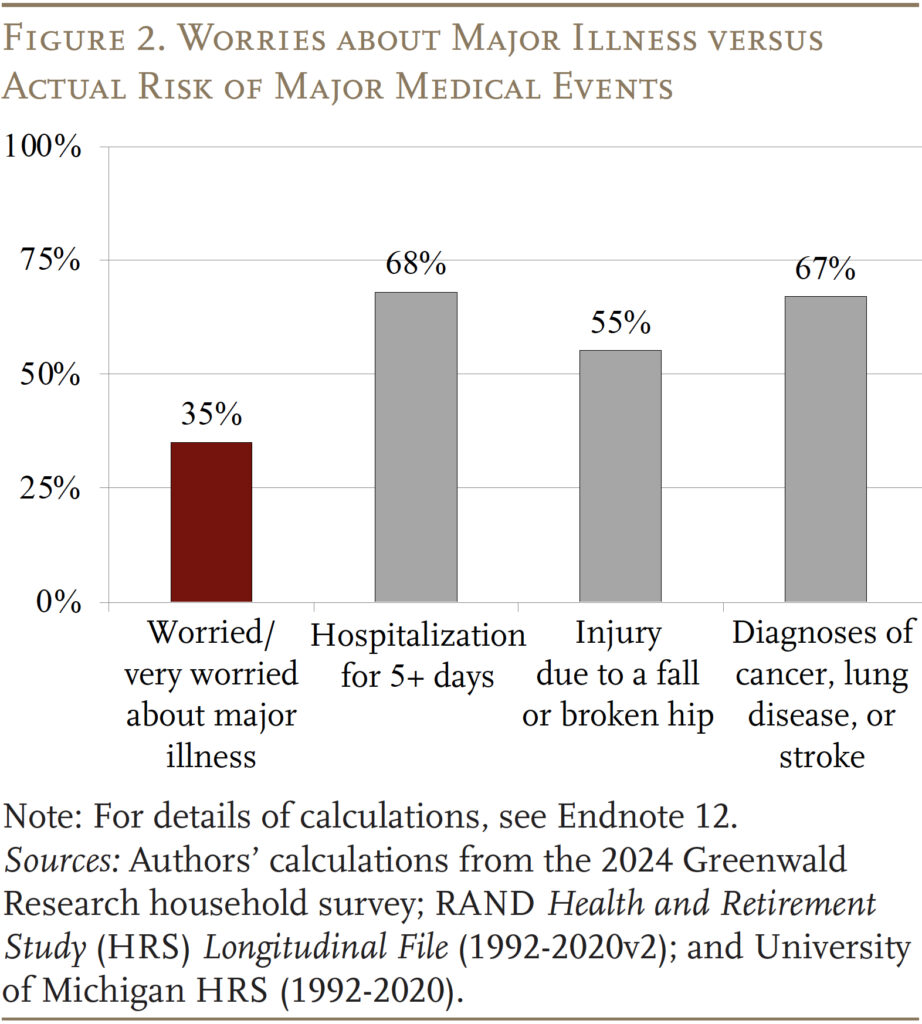

Respondents were then asked whether they were concerned about having a major illness, developing LTC needs, or having cognitive impairment. Interestingly, only about a third of them were concerned with any of these risks.

In reality, households are much more likely to experience a major illness than the 35 percent predicted by survey participants (see Figure 2).12 But the financial implications for households in underestimating their risk of a medical shock may not be that severe because most of these costs are insured.

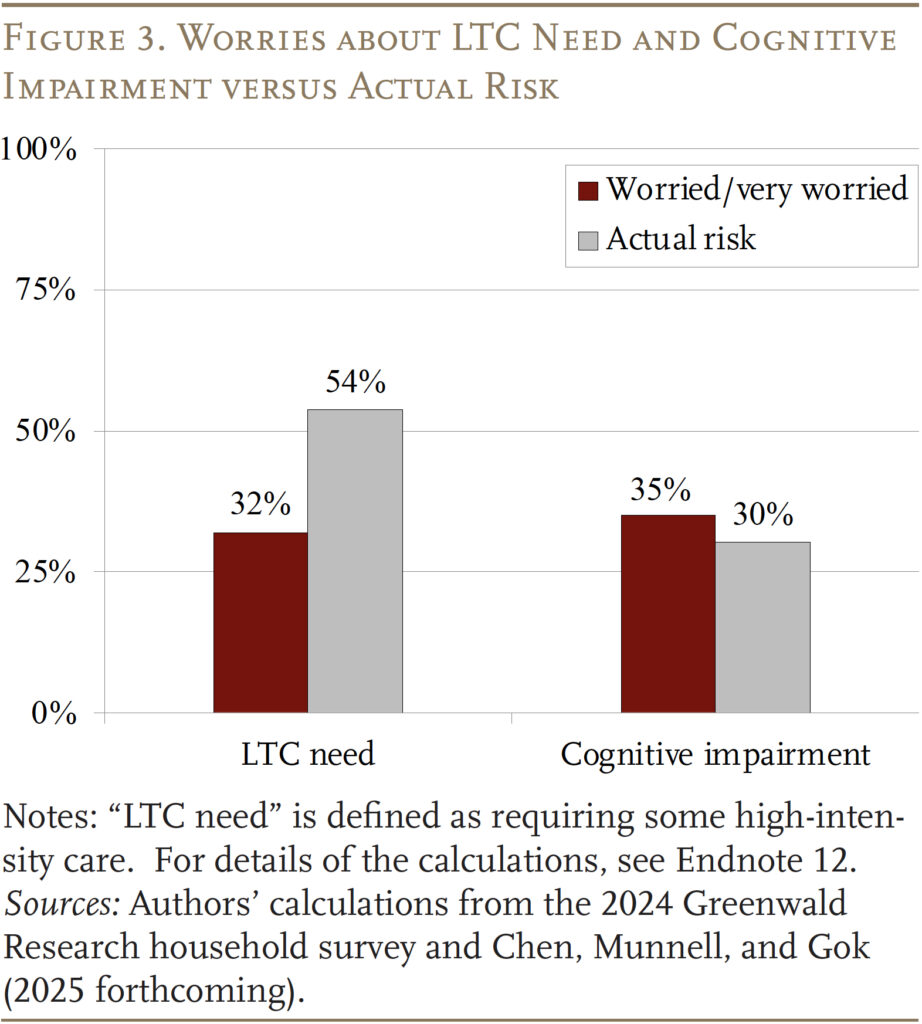

LTC costs, on the other hand, are not well insured, and only 32 percent of households are worried about developing LTC needs. In reality, over half of households ages 65+ will need some high-intensity care (see Figure 3).13 On the other hand, participants’ assessment of the risk of cognitive impairment is very close to reality.

Having a good estimate of the likelihood of healthcare needs as one ages is only half of the retirement planning equation. The other important component is having a good sense of how much these needs might cost.

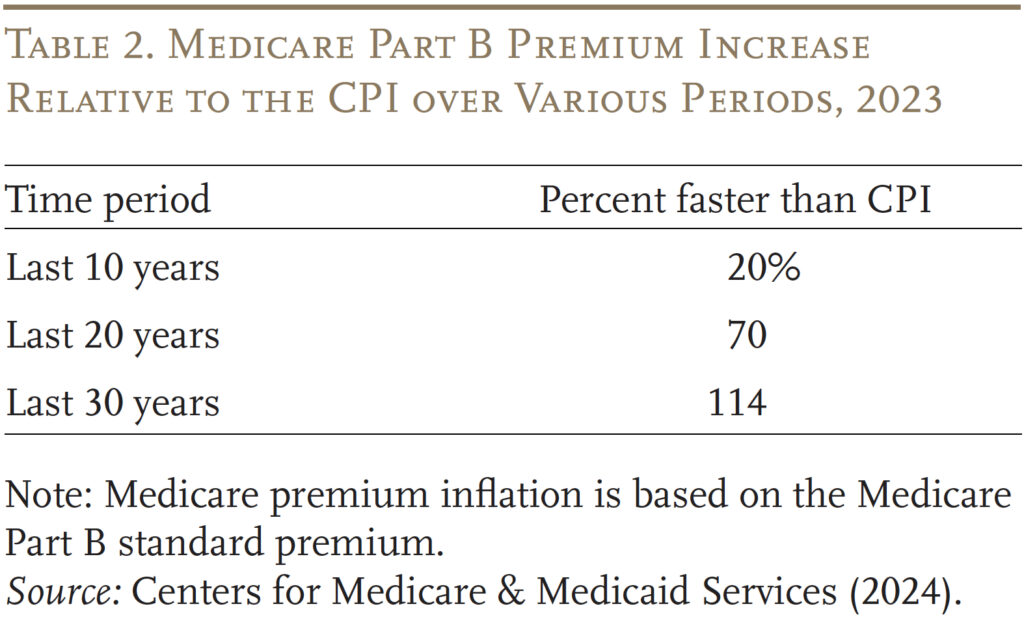

As noted earlier, individual medical risk is well insured; the big risk is general price risk. Indeed, Medicare Part B premiums have grown 20 percent faster than the Consumer Price Index (CPI) in the last 10 years, 70 percent faster in the last 20 years, and more than twice as fast in the last 30 years (see Table 2). Only a third of survey respondents, however, were worried about rising Medicare costs. Fortunately, Part D (prescription drug) premiums have remained relatively low in dollar terms.

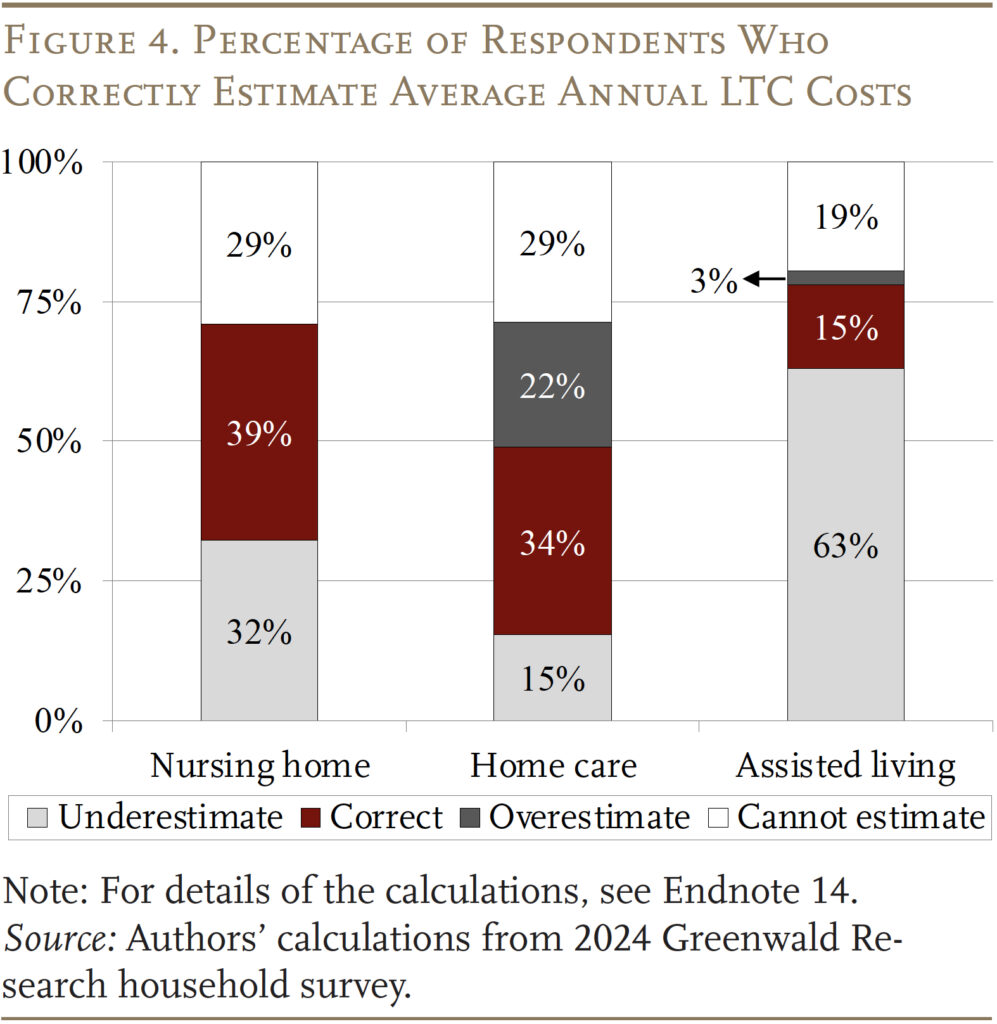

LTC costs, of course, are not well insured, which makes it more important that individuals have a sense of the costs they may face. Figure 4 shows that only 39 percent of older households could correctly estimate the cost of a nursing home, 34 percent for home care services, and only 15 percent for assisted living facilities.14

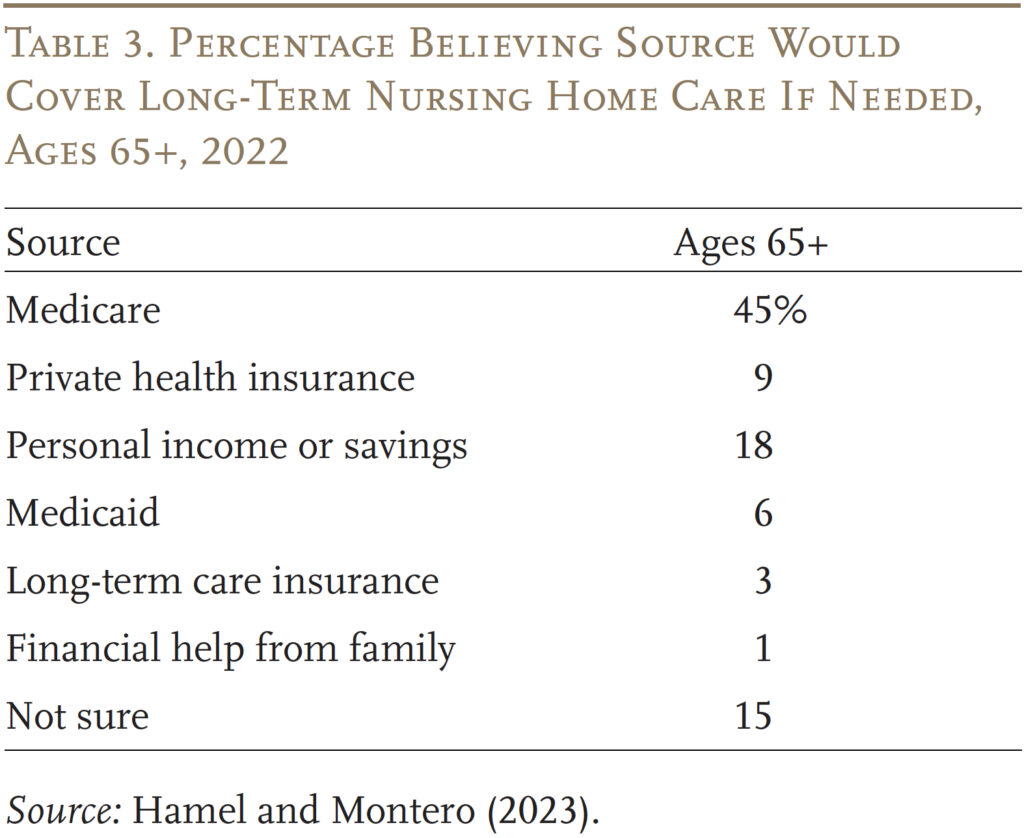

One reason that households have such big misperceptions about both the risks and the costs of LTC is that survey after survey has found that many mistakenly believe that Medicare covers LTC. The most recent comprehensive survey on LTC affordability was conducted by KFF in 2022. The results, presented in Table 3, show that 45 percent of respondents ages 65+ think that Medicare will pay for their LTC. Another 9 percent think that their private health insurance will.15

In short, misperceptions about who bears the cost of LTC may play an important role in how households plan for risks in retirement. The remaining questions are whether financial advisors have a better sense of healthcare risks and costs and whether their advice affects their clients’ perceptions.

The Role of Financial Advisors

About two-thirds of the households surveyed work with a financial advisor. An important question is whether advisors have a better sense of healthcare risks and costs. And if so, do households with an advisor have a better sense of their risks and make better plans? To answer this question, Greenwald Research fielded a survey online of 401 financial advisorsin late July and early August of 2024.16

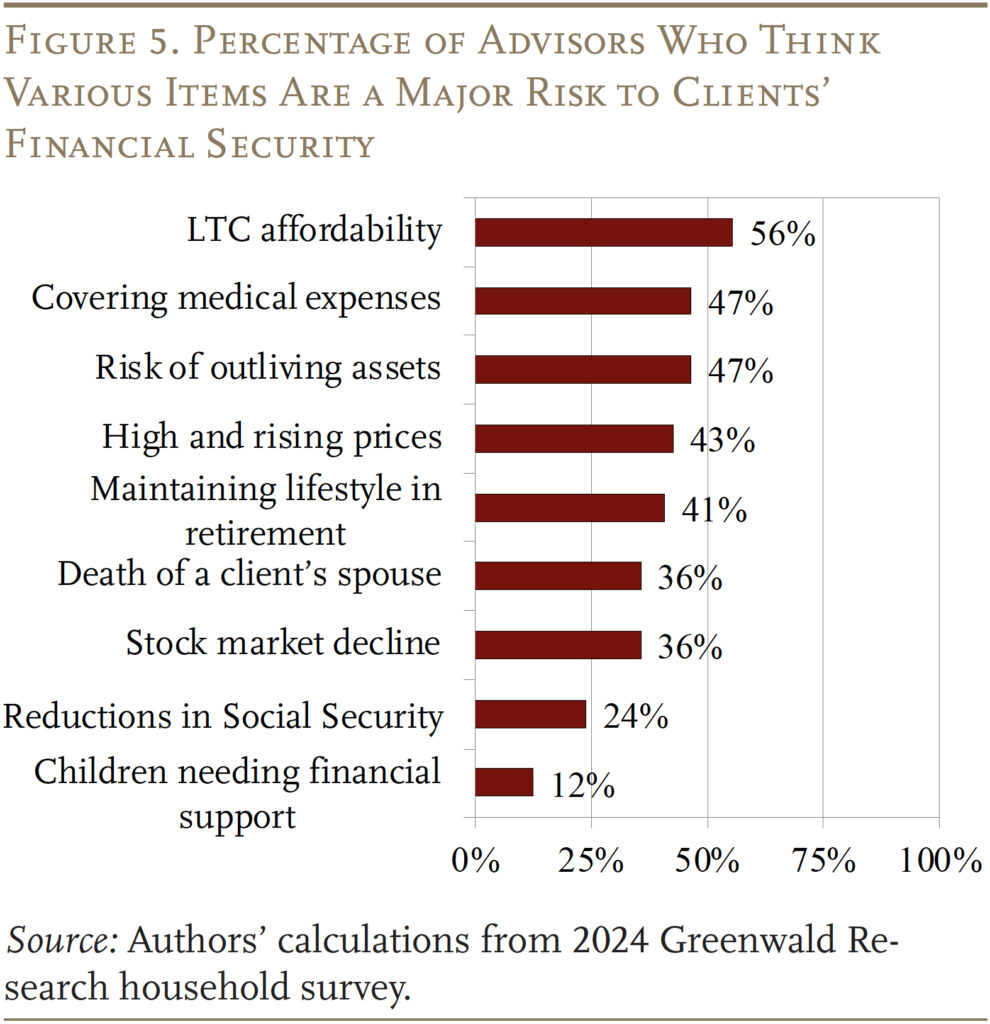

Unlike the households, financial advisors surveyed think that LTC affordability or covering medical costs are the biggest risks their clients face to ensuring a secure retirement (see Figure 5). Almost three-fifths of advisors believe that LTC affordability is a major risk compared to just 33 percent of older households. Similarly, almost half of advisors are worried about their clients covering medical expenses compared to just 24 percent of survey respondents. Advisors also rank these two risks as the highest for their older clients, while investors themselves rank them among the lowest.

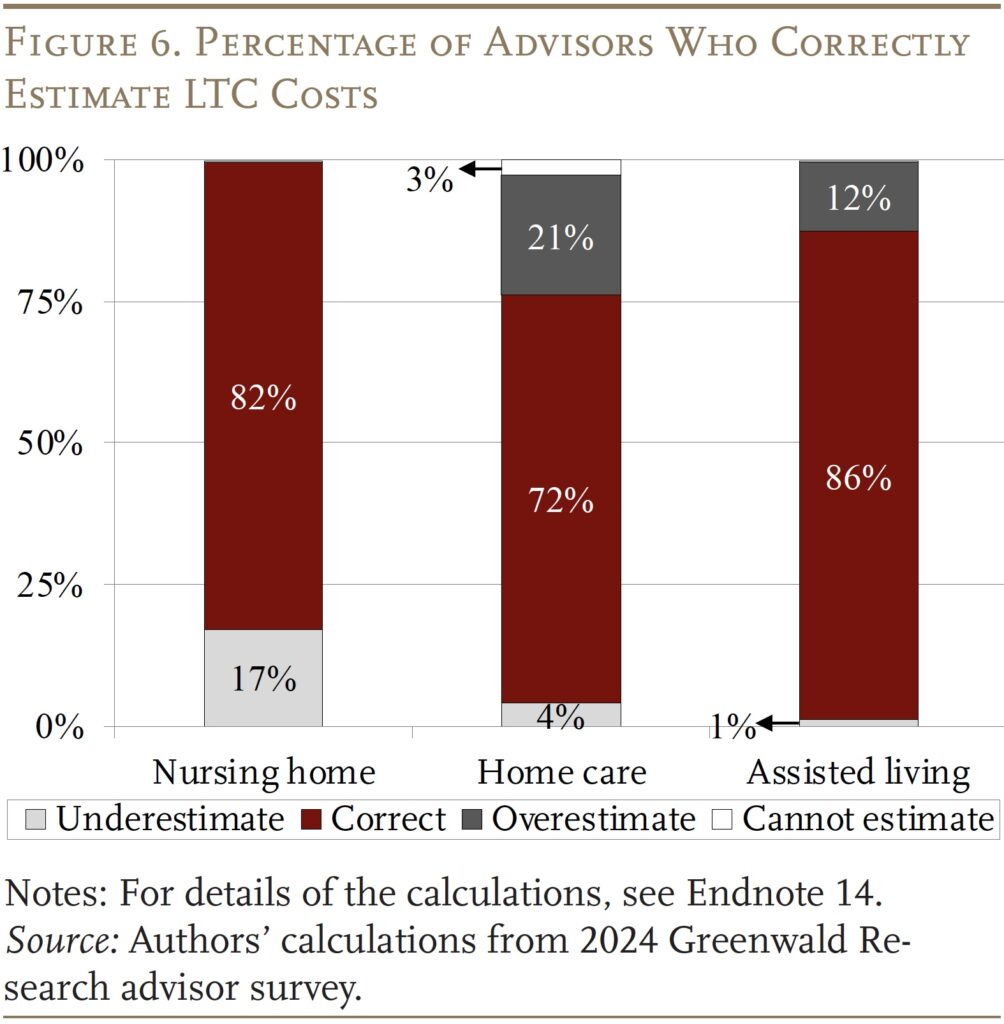

Long-term care affordability heads the list of the major risks facing clients. Indeed, close to 60 percent of advisors think that at least a quarter of their clients will need 3+ years of LTC in retirement. The advisors also have a pretty good sense of how much various LTC services cost, with over 80 percent estimating the correct range for nursing home and assisted living costs (see Figure 6). Advisors were slightly less knowledgeable about home care costs but, even then, nearly three-quarters of advisors provided a good estimate. Moreover, roughly 90 percent of advisors were at least somewhat confident about their cost estimates.

Do Advisors Influence Their Client’s Risk Perceptions?

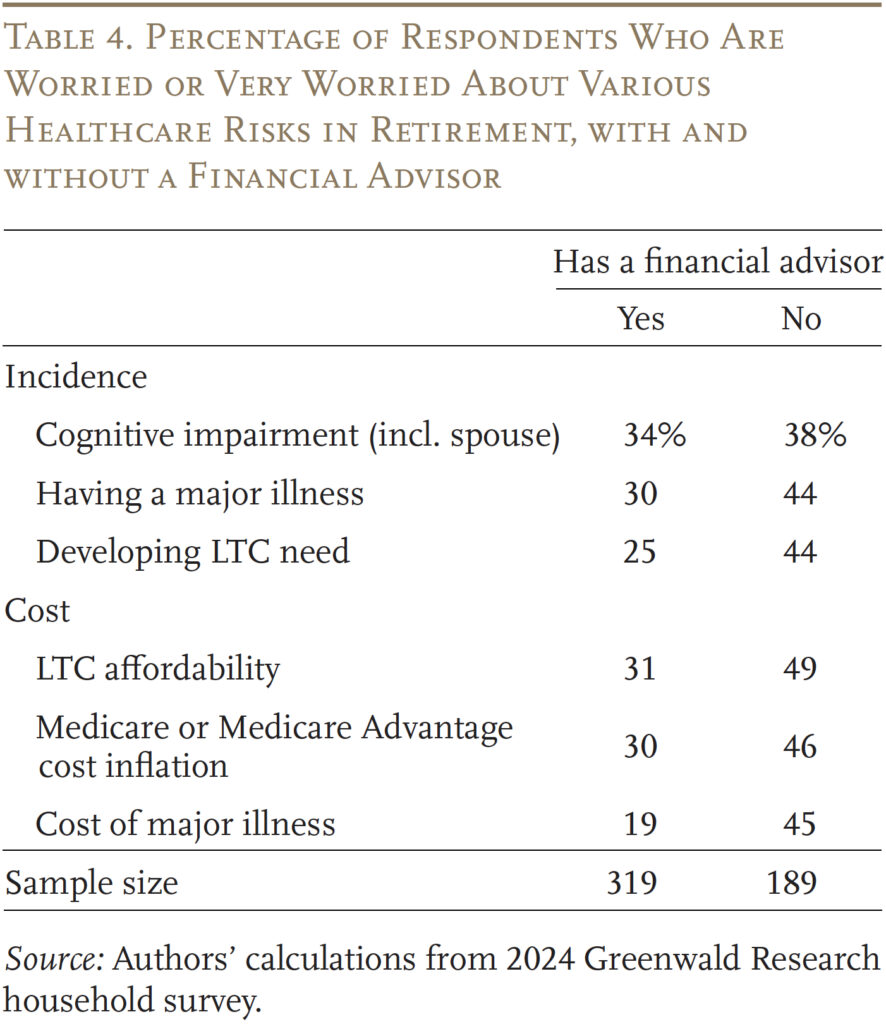

Despite the fact that financial advisors have a pretty good sense of costs, older households with advisors do not seem to have a better sense of their risks. In fact, those with advisors are even less worried about their risks and their ability to cover the cost of major healthcare shocks (see Table 4).

One reason may be that households with a financial advisor are more prepared to handle the risks. For example, they could have LTC insurance, be wealthier, and/or be married and have children who may be able to take care of them. However, regression analysis shows that even after controlling for LTC insurance, wealth, marital status, and other demographic characteristics, those with an advisor are still less concerned about their healthcare risks than those without.

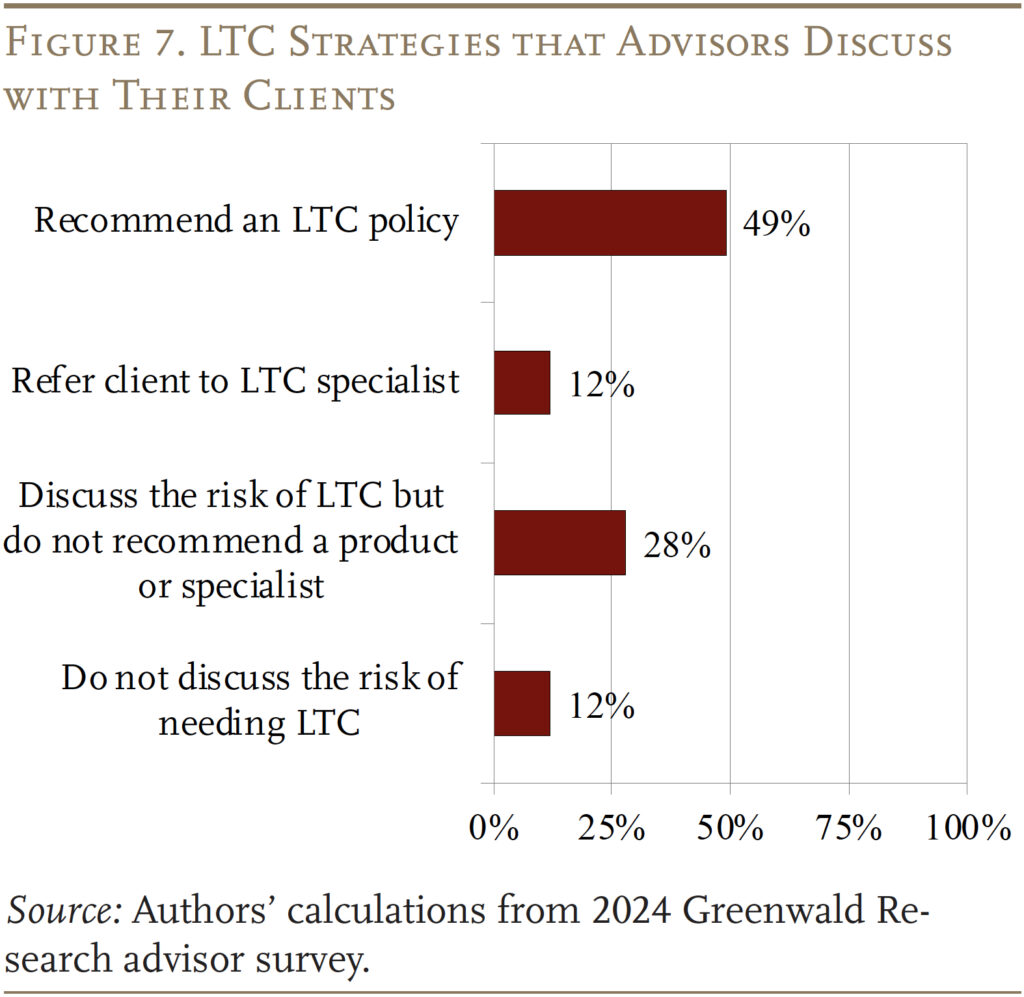

A second reason may be that financial advisors are not discussing these risks with their clients. However, the survey results show that the vast majority of advisors at least discuss LTC risks with their clients and over 60 percent either recommend a policy or recommend their clients to a professional who is more knowledgeable about LTC insurance products (see Figure 7).

If advisors do indeed discuss LTC risks with clients, a third reason for low client knowledge could be that they rely on the advisors to understand these issues for them and do not focus on absorbing the information.

A key question is why advisors, despite their own knowledge and awareness, have very little impact on how older households view these risks. Studies on the impact of financial advisors on retirement security have largely focused on their roles in helping clients make investment decisions.17 A few limited studies have shown that financial advisors can be helpful in guiding households to set savings goals.18 However, virtually no research has focused on how financial advisors can help their clients manage the large spending risks from medical and, particularly, LTC needs in retirement. This area is ripe for future research.

Implications of Underestimating Healthcare Risks

The implications of households underestimating their healthcare risks are that they may not plan well to protect themselves against these risks. The main reasons advisors cite for their clients not buying LTC insurance is that they “underestimate the cost of LTC” or they “would rather not think about needing LTC.”

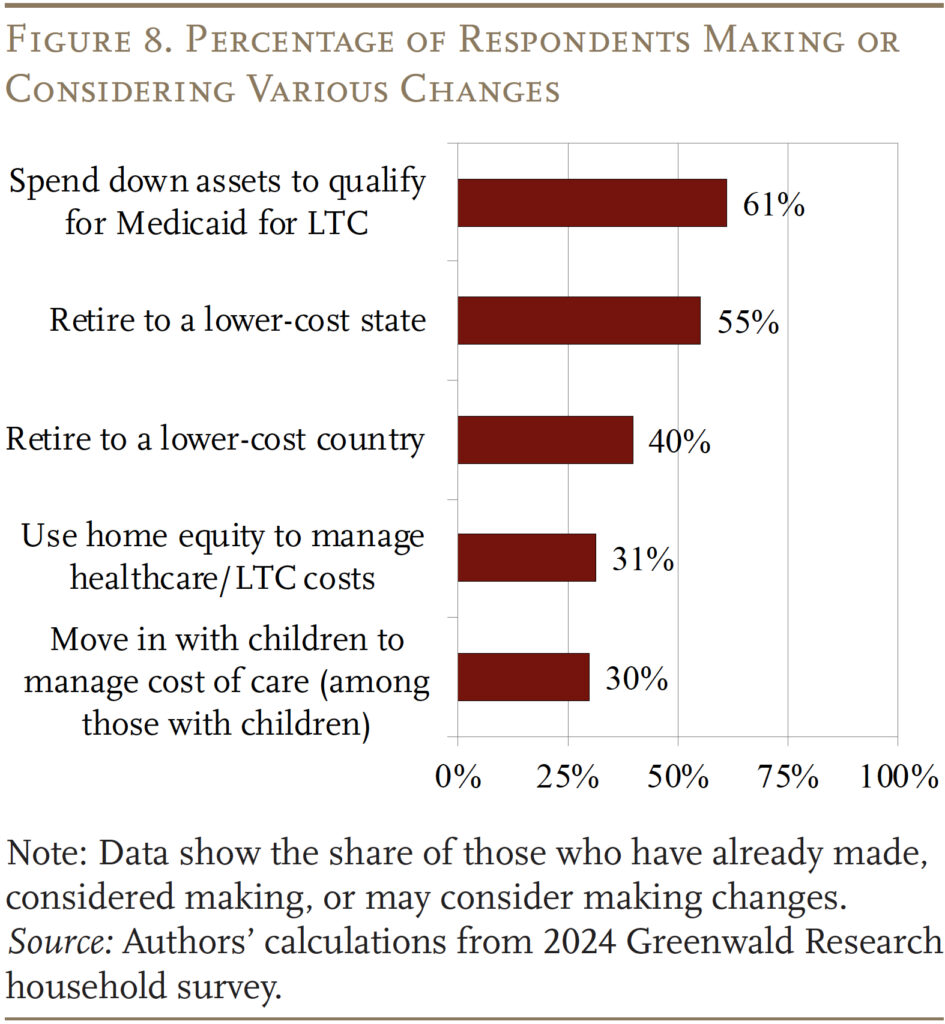

Without the appropriate insurance or resources, older households may have to make substantial adjustments or consider less-preferred options. When asked what contingency plans they would consider if they could not afford their medical or LTC expenses, over 60 percent said they would consider spending down to Medicaid, while only 30 percent said they would consider using their home equity or moving in with their children (see Figure 8). However, many of these preferences may not be realistic.

Spend Down to Medicaid

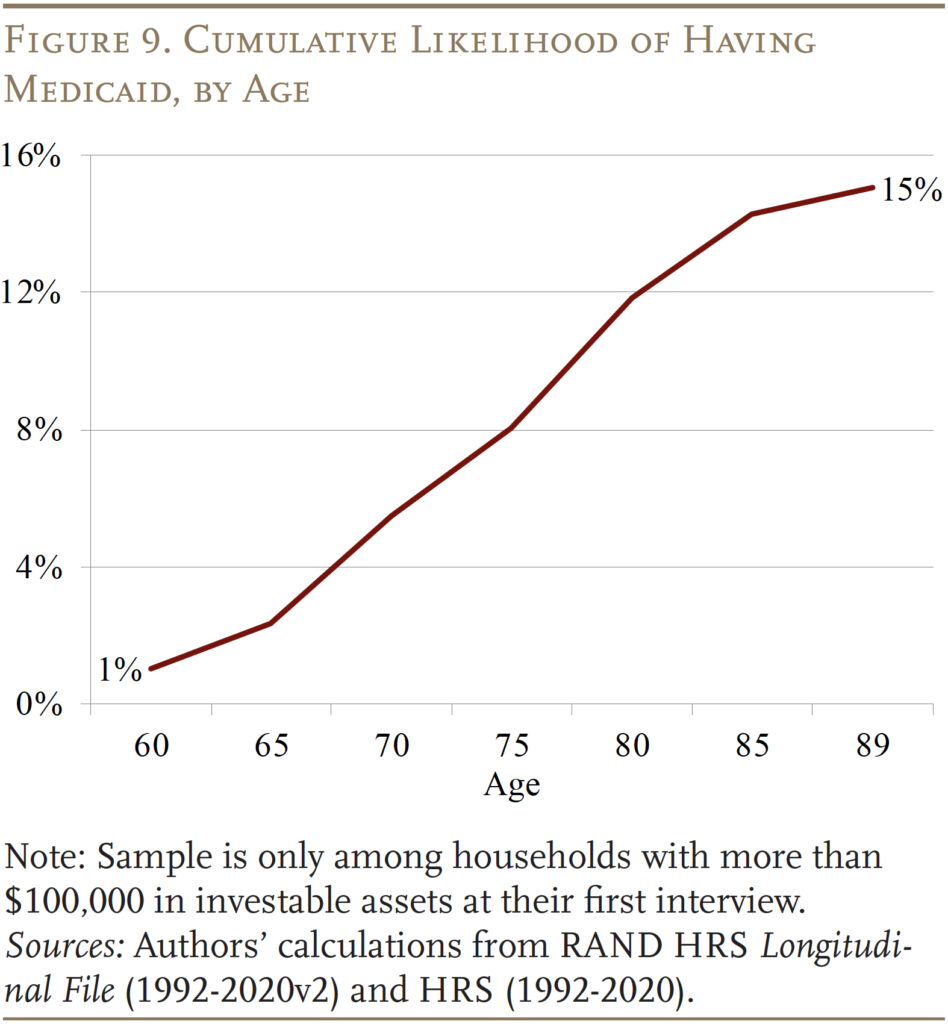

Many older households who believe they can always fall back on Medicaid may not realize that the program’s income and asset limits require impoverishment. Among households with more than $100,000 in investable assets, like those in our survey, almost none would qualify based on the standard income rules because their Social Security benefit and defined benefit income would put them above the limit. Several states have special income rules for long-term care with slightly higher limits. Even then, 70 percent of households in our sample would not qualify. In reality, only 15 percent of households with more than $100,000 in initial assets will actually end up on Medicaid, compared to the 60 percent of households who think that spending down to Medicaid is an option for them (see Figure 9).

Tapping Home Equity

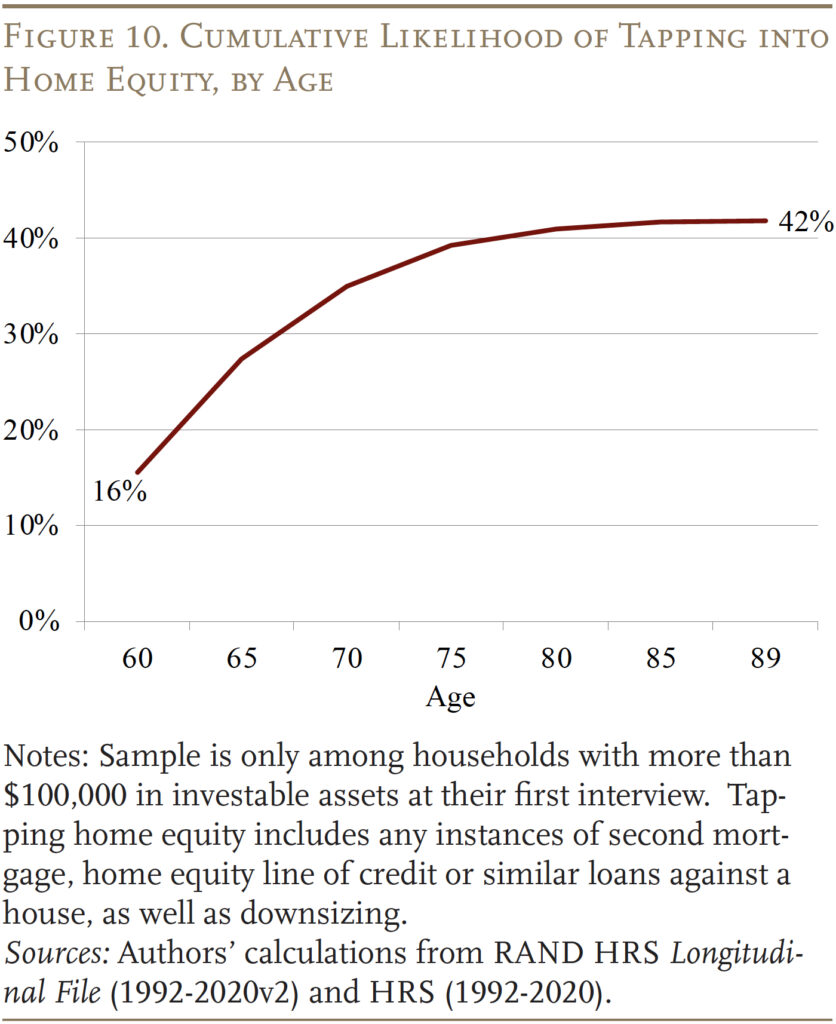

One of the least popular contingency options for financing healthcare costs is tapping home equity. Less than a third of households said they would consider it. However, in reality, over 40 percent will tap home equity in retirement – either by getting a second mortgage, applying for a home equity line of credit or other loans against the house, or downsizing and moving to a less valuable house (see Figure 10).19

Living with Children

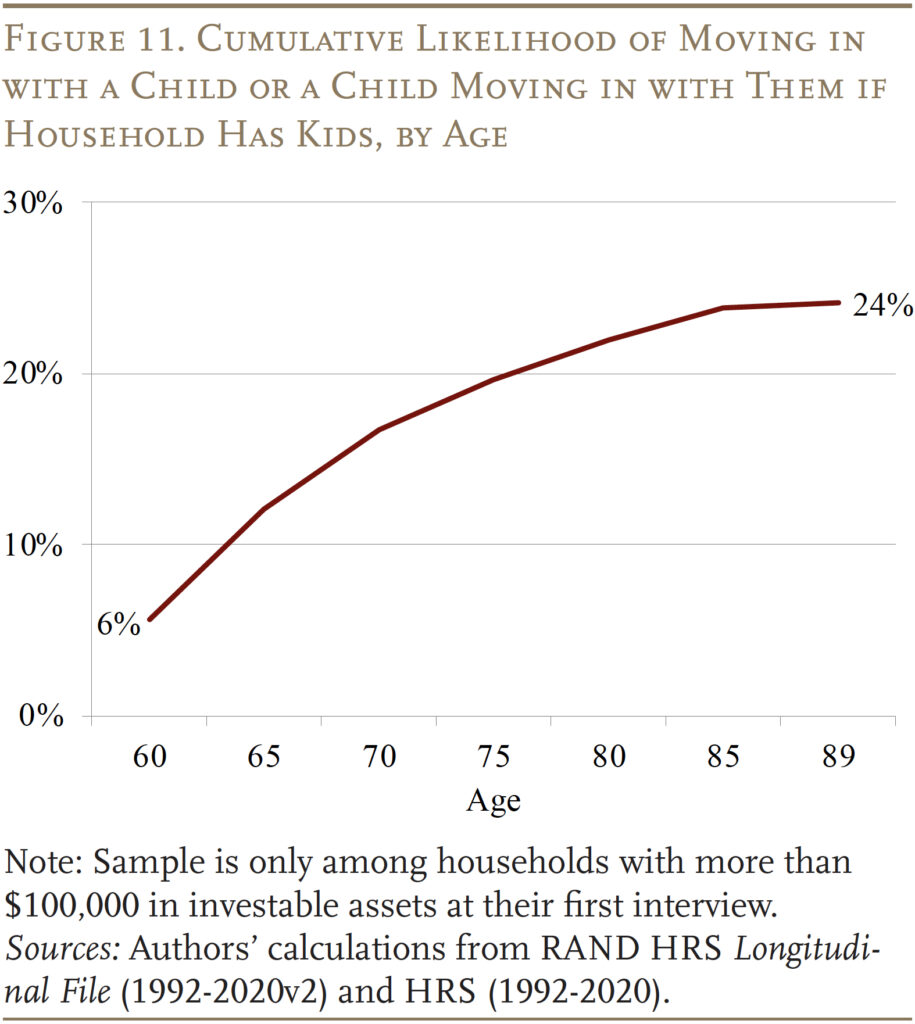

Finally, another unpopular option for managing healthcare needs among respondents is moving in with children. Again, less than a third say they would consider this option. Interestingly, in the real world, only about a quarter of older households in our wealth group end up living with their children (see Figure 11). So, this option does seem like the least preferred back-up if plans fail.

Conclusion

The uninsured components of healthcare costs in retirement can be substantial, and older households need to have an accurate perception of these risks to plan their spending appropriately.

The results of new surveys show that older households tend to underestimate their healthcare risks in retirement and have very little sense of how much medical shocks or LTC services may cost. Advisors, on the other hand, have a better sense of the prevalence and costs. Interestingly, older households who work with advisors do not seem to know more about these risks or costs than those without an advisor. It is not clear why advisors have little impact on their clients’ perceptions.

The implications of older households underestimating healthcare risks are that many may have to make substantial adjustments or consider unpalatable options. The majority of older households say they would spend down to Medicaid and prefer to preserve their home equity. In reality, many end up tapping home equity and only a minority end up on Medicaid.

References

American Association for Long-term Care Insurance. 2020. Long-Term Care Insurance Facts – Data – Statistics – 2020 Reports. Westlake Village, CA.

Belbase, Anek, Anqi Chen, Patrick Hubbard, and Alicia H. Munnell. 2021. “Who Will Have Unmet Long-Term Care Needs and How Does Medicaid Help?” Issue in Brief 21-18. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2024. Annual Report of the Boards of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Funds. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Chalmers, John and Jonathan Reuter. 2020. “Is Conflicted Investment Advice Better Than No Advice?” Journal of Financial Economics 138(2): 366-387.

Chen, Anqi, Alicia H. Munnell, and Gal Wettstein. 2025. “Do Retirement Investors Accurately Perceive Healthcare Risks, and Do Advisors Help?” Working Paper 2025-3. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Chen, Anqi, Alicia H. Munnell, and Gal Wettstein. 2025 (forthcoming). “How Do Retirees Cope with Uninsured Healthcare Costs?” Working Paper. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Chen, Anqi, Alicia H. Munnell, and Nilufer Gok. 2025 (forthcoming). “Do Households have a Good Sense of Their Long-Term Care Risks?” Working Paper. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Chokshi, Niraj. 2017. “Out of the Office: More People Are Working Remotely, Survey Finds.” (February 15). New York, NY: The New York Times.

Favreault, Melissa and Judith Dey. 2015. “Long-Term Services and Supports for Older Americans: Risks and Financing Research Brief.” Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation.

Freedman, Vicki and Brenda Spillman. 2014. “The Residential Continuum From Home to Nursing Home: Size, Characteristics and Unmet Needs of Older Adults.” The Journals of Gerontology: Series B 69(1) S42-S50.

French, Kenneth R. and James M. Poterba. 1991. “Investor Diversification and International Equity Markets.” The American Economic Review 81(2): 222-226.

Genworth Financial. 2023. “Genworth Releases Cost of Care Survey Results for 2023: Twenty Years of Tracking Long-Term Care Costs.” Richmond, VA.

Grinblatt, Mark and Matti Keloharju. 2001. “How Distance, Language, and Culture Influence Stockholdings and Trades.” The Journal of Finance 56(3): 1053-1073.

Goetzmann, William N. and Alok Kumar. 2008. “Equity Portfolio Diversification.” Review of Finance 12(3): 433-463.

Gohringer, Kimberly. 2017. “Telecommuting and Dependent Care: Work Solutions for Caregivers.” Eugene, OR: Virtual Vocations website.

Gruber, Jonathan and Kathleen M. McGarry. 2023. “Long-term Care in the United States.” Working Paper 31881. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Hackethal, Andreas, Michael Haliassos, and Tullio Jappelli. 2012. “Financial Advisors: A Case of Babysitters?” Journal of Banking & Finance 36(2): 509-524.

Hamel, Liz and Alex Montero. 2023. “The Affordability of Long-Term Care and Support Services: Findings from a KFF Survey.” San Francisco, CA: KFF.

Hou, Wenliang. 2020. “How Accurate Are Retirees’ Assessments of Their Retirement Risk?” Working Paper 2020-14. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Johnson, Richard W. and Joshua M. Wiener. 2006. “A Profile of Frail Older Americans and Their Caregivers.” Occasional Paper Number 8. Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

Johnson, Richard W. and Judith Dey. 2022. “Long-Term Services and Supports for Older Americans: Risks and Financing, 2022.” Research Brief. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation.

Kramer, Marc M. 2012. “Financial Advice and Individual Investor Portfolio Performance.” Financial Management 41(2): 395-428.

Kim, Kyoung T., Tae-Young Pak, Su H. Shin, and Sherman D. Hanna. 2018. “The Relationship Between Financial Planner Use and Holding a Retirement Saving Goal: A Propensity Score Matching Analysis.” Financial Planning Review 1(1-2): e1008.

Liu, Zhikun, Michael Finke, and David Blanchett. 2024. “Professional Financial Advice and Investor Behavior During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Financial Planning Review 7(1): e1172.

Marsden, Mitchell, Cathleen D. Zick, and Robert N. Mayer. 2011. “The Value of Seeking Financial Advice.” Journal of Family and Economic Issues 32: 625-643.

McInerney, Melissa, Matthew S. Rutledge, and Sara Ellen King. 2022. “How Much Does Health Spending Eat Away at Retirement Income?” Issue in Brief 22-12. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Radu, Sintia. 2018. “How Soon Will You Be Working from Home? Telecommuting Might Not Just Be A Company Perk in the Next Decade.” (February 16). Washington, DC: U.S. News & World Report.

RAND. Health and Retirement Study Longitudinal File, 1992-2020v2. Santa Monica, CA.

Shapira, Zur and Itzhak Venezia. 2001. “Patterns of Behavior of Professionally Managed and Independent Investors.” Journal of Banking & Finance 25(8): 1573-1587.

Spillman, Brenda C. 2009. “Policy Analyses Using the 2004 National Long-Term Care Survey.” Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation.

Spillman, Brenda C., Eva H. Allen, and Melissa Favreault. 2021. “Informal Caregiver Supply and Demographic Changes: Review of the Literature.” Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation.

Spillman, Brenda and Liliana Pezzin. 2000. “Potential and Active Family Caregivers: Changing Networks and the ‘Sandwich Generation.’” The Milbank Quarterly 78(3): 347-374.

Spillman, Brenda, Vicki Freedman, Judith Kasper, and Jennifer Wolff. 2020. “Change Over Time in Caregiving Networks for Older Adults With and Without Dementia.” The Journals of Gerontology: Series B 75(7): 1563-1572.

U.S. Congress Joint Economic Committee. 2019. An Invisible Tsunami: “Aging Alone” and Its Effect on Older Americans, Families, and Taxpayers. SCP Report No. 1-19. Washington, DC.

University of Michigan. Health and Retirement Study, 1992-2020. Ann Arbor, MI.

von Gaudecker, Hans-Martin. 2015. “How Does Household Portfolio Diversification Vary with Financial Literacy and Financial Advice?” The Journal of Finance 70(2): 489-507.

Wettstein, Gal and Alice Zulkarnain. 2019. “Will Fewer Children Boost Demand for Formal Caregiving?” Working Paper 2019-6. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Wolff, Jennifer and Judith Kasper. 2006. “Caregivers of Frail Elders: Updating a National Profile.” The Gerontologist 46(3): 344-356.

Endnotes

- Chen, Munnell, and Wettstein (2025). ↩︎

- McInerny, Rutledge, and King (2022). ↩︎

- This estimate is consistent with Favreault and Dey (2015); Belbase et al. (2021); and Johnson and Dey (2022). ↩︎

- See Gruber and McGarry (2023) and American Association of Long-term Care Insurance (2020). The market for private stand-alone LTC insurance peaked in the early-2000s. Over time, many insurance providers have dropped out of the market or consolidated. By the early 2010s, many large insurers stopped selling LTC policies. Recently, there has been some increase in LTC policies that are combined with life insurance or annuities (Spillman et al. 2020). ↩︎

- For households where one spouse is still living in the community, their house can be exempt from the Medicaid asset limits. In some states, the community-living spouse’s 401(k) or IRA assets can also be exempt. Additionally, a certain amount of the couple’s income is protected to prevent spousal impoverishment, although the rules vary by state. ↩︎

- See also Spillman (2009); Johnson and Wiener (2006); Spillman and Pezzin (2000); Wolff and Kasper (2006); and Freedman and Spillman (2014). ↩︎

- Additionally, children and other relatives will be limited in how much care they can provide if they live far away. The share of retirees with children who lived within 10 miles fell from 68 percent to 55 percent between 1994 and 2004 (U.S. Congress Joint Economic Committee 2019). However, some studies suggest that the growth in remote work, even before the pandemic, may help children remain closer to their parents (Chokshi 2017; Radu 2018; and Gohringer 2017). Finally, declining fertility also suggests that fewer kids will be available to care for older parents in the coming decades (Wettstein and Zulkarnain 2019). ↩︎

- Genworth Financial (2023). ↩︎

- Spillman et al. (2020). ↩︎

- Although not always the case, home care can be more cost-effective than nursing home care (Spillman, Allen, and Favreault 2021). ↩︎

- See Hou (2020). ↩︎

- Actual risk is calculated for a sample of household heads born in 1931-1941 who had $100,000 in investable assets (in 2023 dollars), who were not in a nursing home or on Medicaid during their first interview, and who have died since or have been interviewed at least once after age 80. The risks are for the household (incidence for either spouse) and exclude hospitalizations right before death. ↩︎

- These numbers are slightly higher than the share of individuals who will have high-intensity needs in Table 1 because they represent household-level risks while Table 1 represents individual-level risks. ↩︎

- Since LTC costs vary substantially across geographic area, the calculations are based on a broad range of estimated costs. Respondents are categorized as being correct if they estimate that nursing home costs are at least $75,000 per year, home care costs are between $20-$50 per hour ($45,760-$114,400 per year), and assisted living costs are between $50,000-$150,000 per year. ↩︎

- Hamel and Montero (2023). ↩︎

- Respondent qualifications included the following criteria: 1) currently work as a financial professional; 2) work with a national full-service broker-dealer, regional broker-dealer, independent broker-dealer, RIA, bank broker-dealer, or insurance broker-dealer; 3) been a financial professional for at least three years; 4) derive at least 50 percent of income from individual sales; 5) have at least $30 million in AUM; 6) make recommendations directly to clients; 7) at least 40 percent of clients are ages 50+; and 8) serve at least 75 clients. ↩︎

- A number of papers have examined the impact of financial advisors on household finances, with mixed results: (Shapira and Venezia 2001; von Gaudecker 2015; Hackethal, Haliassos, and Jappelli 2012; Kramer 2012; and Chalmers and Reuter 2020). Advisors could help clients manage risks by diversifying their portfolios (Goetzmann and Kumar 2008; French and Poterba 1991; and Grinblatt and Keloharju 2001) or reducing risks during financial downturns (Liu, Finke, and Blanchett 2024). ↩︎

- See Kim et al. (2018) and Marsden, Zick, and Mayer (2011). ↩︎

- In a new study (Chen, Munnell, and Wettstein 2025 forthcoming), we find that older households who draw down their home equity often do so in response to a long-term care shock. ↩︎