Do Pension Benefit Cuts Encourage Public Employees to Leave?

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Evidence from Rhode Island says “yes.”

The Center for Retirement Research just published a brief on how state public sector workers respond to a cut in their future pension benefits, using wonderful data obtained from the state of Rhode Island. The results show that benefit cuts encourage government workers to leave their jobs, but that the size of the response is small relative to the budgetary savings.

The 2005 reform of the Employees’ Retirement System of Rhode Island (ERSRI) raised the normal retirement age, reduced the multiplier that determines benefit levels, and capped future cost-of-living adjustments. Importantly, the reform did not affect vested members, but it also ignored local government employees who participate in a separate pension system, the Municipal Employees Retirement System (MERS).

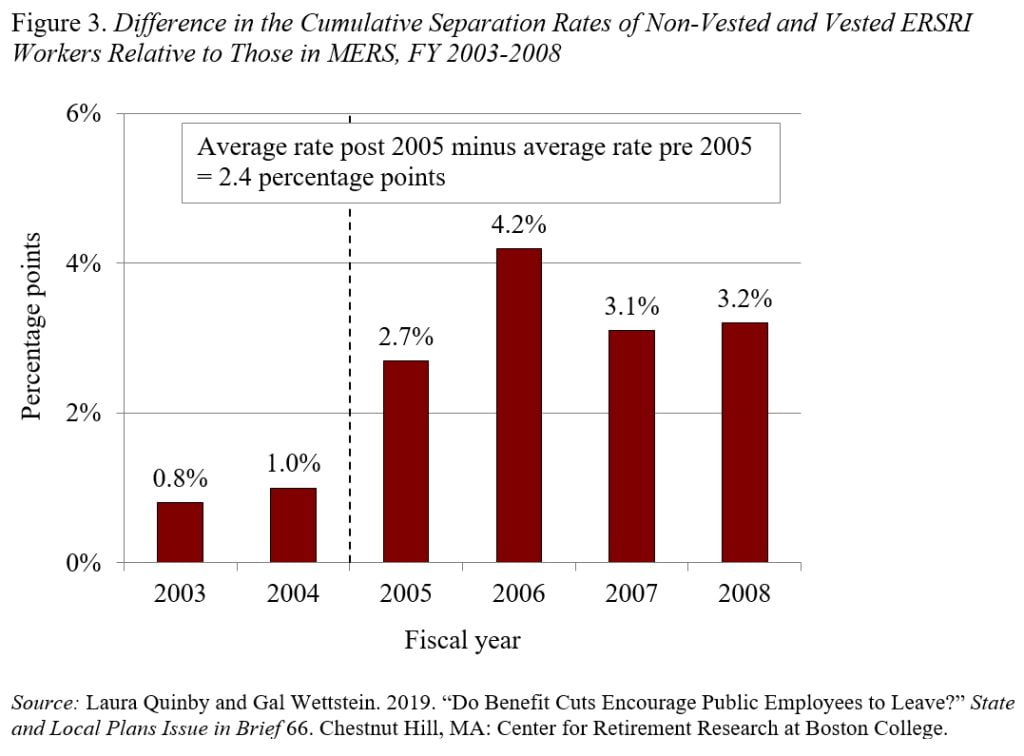

To assess whether these cuts encouraged workers to leave for the private sector, the analysis proceeds in three steps. It’s a little complicated but really clever. First, the researchers follow individual ERSRI members who were employed at the beginning of 2003, and calculate how many non-vested (who were affected by the cuts) and vested (who were not affected by the cuts) employees had left state government by the end of each year between 2003 and 2008. Figure 1 displays the difference in their cumulative separation rates. After the reform, the gap between non-vested and vested workers rose by 2 percentage points – from about 4 percentage points to about 6 percentage points – and remained at this higher level for a few years.

This finding suggests that the benefit cut spurred separations. However, the difference in the cumulative separation rates was already trending upward in 2004, the year before the benefit cut. This trend could have been due to many factors, including a strong economy that may have disproportionately lured short-tenure workers to the private sector.

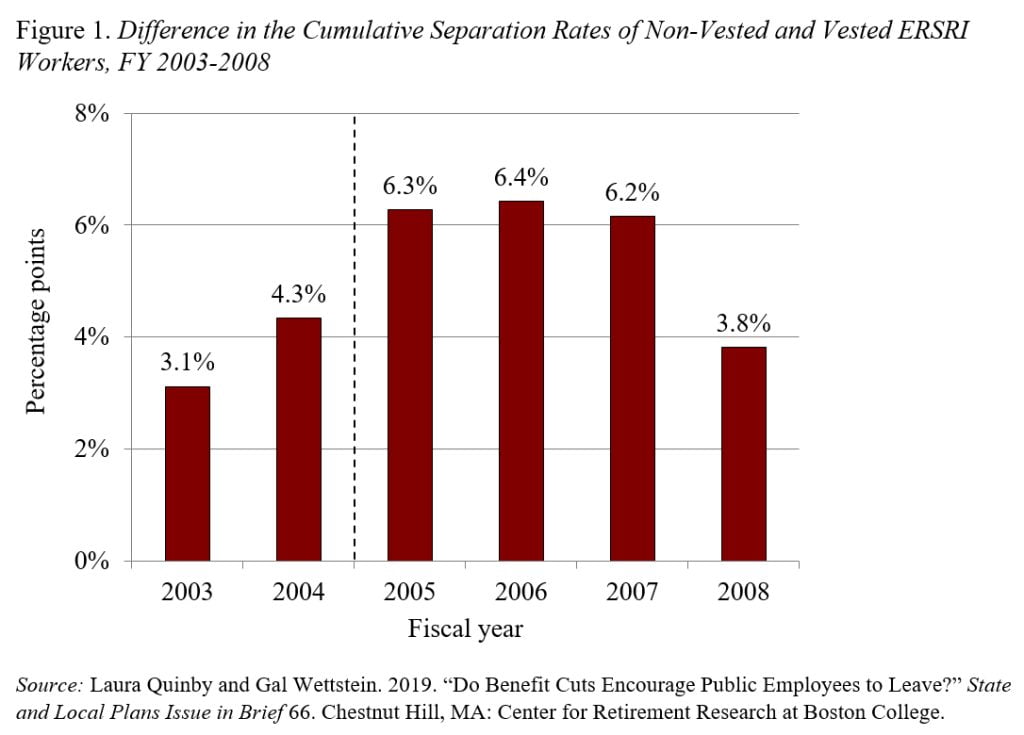

So, the second step is to control for these other factors by looking at the separation patterns of municipal employees in MERS, who were not affected by the cuts. Reassuringly, MERS displayed the same upward trend in 2004 as ERSRI, but stabilized in 2005 and subsequently declined (see Figure 2). The fact that ERSRI and MERS diverged in the year of the pension reform indicates that the benefit cut encouraged some state employees and teachers to leave their jobs.

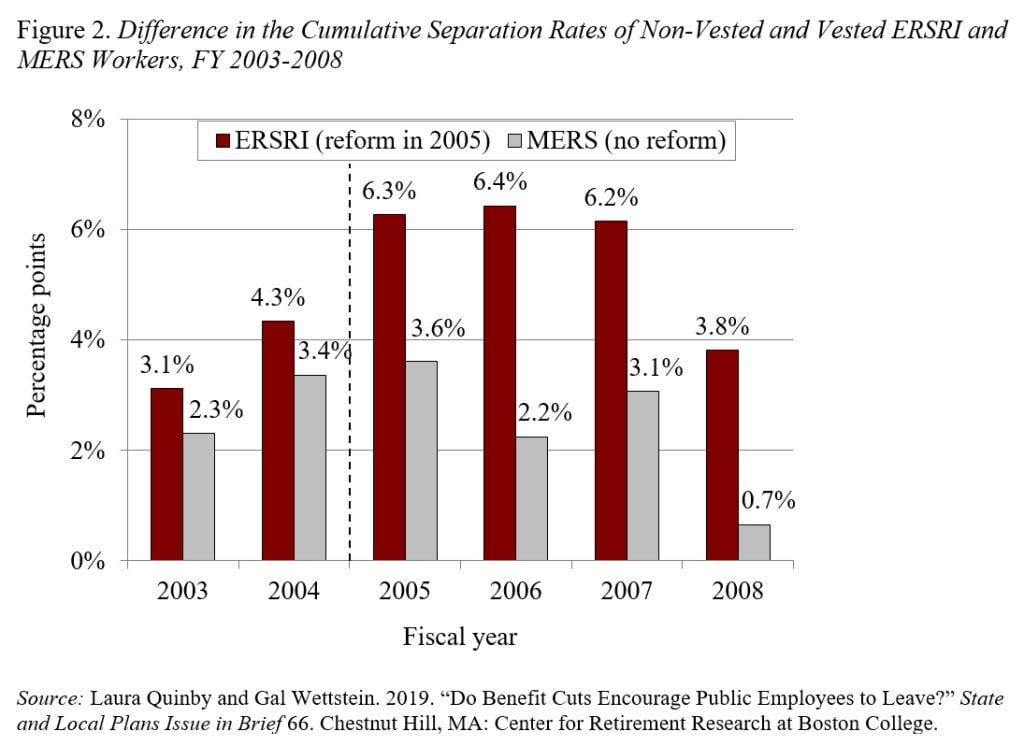

The last step is to simply subtract the red bars in Figure 2 from the gray bars to provide an ERSRI-MERS comparison. The final result shows that, in 2004, the difference in separation between non-vested and vested members of ERSRI was 1-percentage-point higher than the difference in separation between non-vested and vested members of MERS (see Figure 3). Then it suddenly jumped up by 2.4 percentage points (the average in the post-reform period minus the average in the pre-reform period). In other words, the benefit cut in ERSRI caused an approximately 2.4-percentage-point increase in the rate at which current employees left for the private sector. The full paper underlying this research confirms that the estimated effect is statistically significant.

The impact of benefit cuts on employment – although small relative to the pension savings – is an important finding, because a number of state and local pension systems have persistently low levels of funding and may eventually be forced to cut benefits for current employees.