Does Employer Concentration Reduce Labor Force Participation?

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

The accumulating evidence suggests that it does.

The labor force participation of prime-age workers has been declining steadily over the past two decades. One possible factor may be the concentration of employers in local labor markets. When firms possess greater bargaining power, they can drive down wages, which, in turn, discourages labor force participation. Employer “concentration” is a hot topic among economists and has filtered through to policymakers. The president has issued an executive order for the Federal Trade Commission to consider labor-market – as well as product-market concentration – when evaluating mergers.

A recent study by my colleagues Anqi Chen, Laura Quinby, and Gal Wettstein examines whether markets with higher employer concentration are associated with lower labor force participation rates and whether the relationship is weaker for employees with more bargaining power, such as those covered by unions.

The analysis proceeds in three steps. The first step is to construct a Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) of employer concentration. The HHI, a commonly accepted measure of market concentration on the product side, is calculated by squaring the market share of each firm’s employment at the county and industry level and summing the squared values. The index varies between 0 (extremely diffuse) and 1 (a monopsony). The tricky part of the exercise is getting the data to link employers to each county and to link employees to each employer.

Once all the hard work is done, the next step is to estimate regressions to determine whether a high HHI is correlated with lower labor force participation rates and whether the correlation is weaker when workers have bargaining power to counteract employer bargaining power, by estimating the interaction effect of concentration and union coverage.

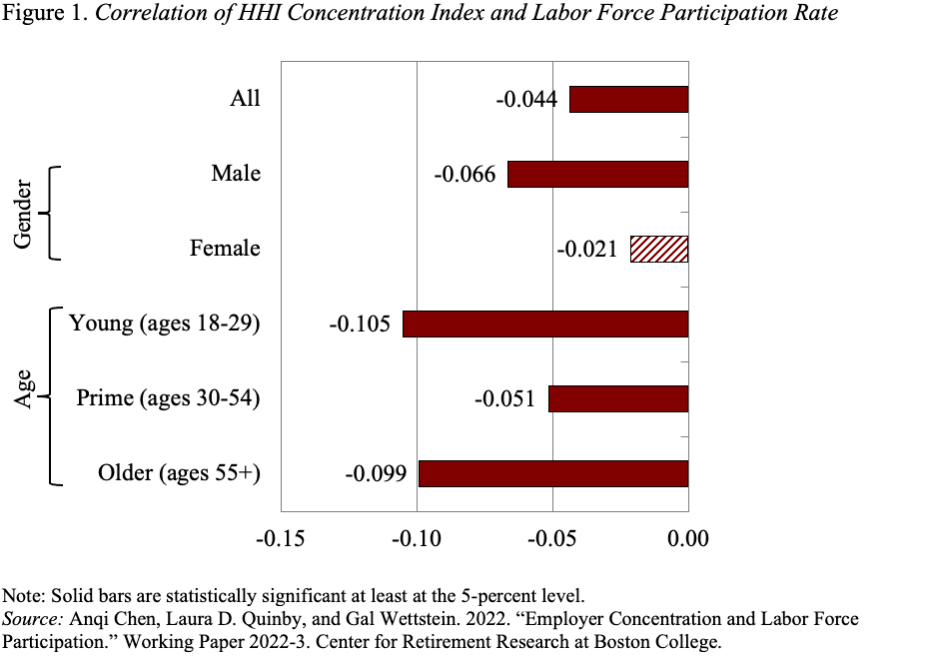

As it turns out, the correlation between the HHI and the labor force participation rate across counties is negative, large, and statistically significant (see Figure 1). That is, places where employers are more concentrated tend to have lower labor force participation. For example, a move from perfect competition (an HHI of 0) to monopsony (an HHI of 1) is associated with a 4.4-percentage-point decline in the labor force participation rate for all workers. This pattern holds in a variety of different cuts of the population: both for men and women (although not statistically significant for women) and among young, prime-age, and older workers.

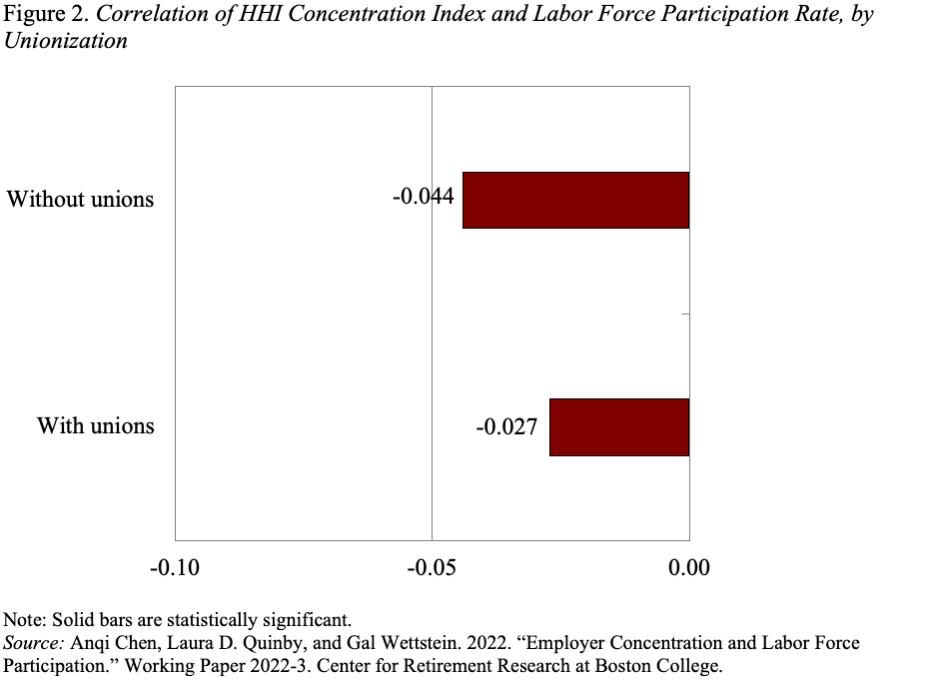

The second question is whether union power can offset some of the impact of monopsony power. The answer appears to be “yes.” At the mean of HHI, the negative correlation between employer concentration and labor force participation in the absence of unions is 0.044; add unions and that correlation drops to 0.027 (see Figure 2). One possible mechanism behind this result is that unions drive up wages, making more non-employed workers more willing to look for work.

So, there you have it – one more piece of evidence that employer concentration has a real impact on labor market outcomes!