Does Temporary Disability Insurance Help or Hurt the Social Security Disability Program?

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

It reduces Social Security applications and new beneficiaries.

Enthusiasm seems to be running high for Family and Medical Leave programs. My views are mixed: as a human I can see some benefit; as a person trying to run a small organization, extended leaves are just annoying.

Some critics have a more specific concern – namely, that Temporary Disability Insurance (TDI), which is typically included in these programs, could serve as an on-ramp to Social Security’s Disability Insurance (DI) program. Since TDI benefits are not considered earnings, they could provide needed funds during the lengthy application process, encouraging workers to apply, and ultimately increasing the DI rolls.

In contrast, enthusiasts of a national paid leave program argue that TDI would allow workers – particularly older workers who are most at risk – to adjust to health shocks and resume employment, reducing reliance on DI.

In a recent study, my colleagues tried to sort out the evidence. They began with a sample of full-time workers ages 50-60 who experience a new work-limiting shock and tracked these workers for two to four years, allowing them ample time to submit a DI application. They broke the sample into two groups: 1) those with a persistent and severe disability who were potential DI applicants; and 2) those with less severe impairments who are unlikely to qualify for DI.

And they took advantage of the fact that workers can access TDI only if they reside in states with TDI mandates or if their employer voluntarily offers these benefits. Since data on employer coverage is limited, they compared workers residing in states with longstanding TDI mandates – California, New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island – with similar workers in other states.

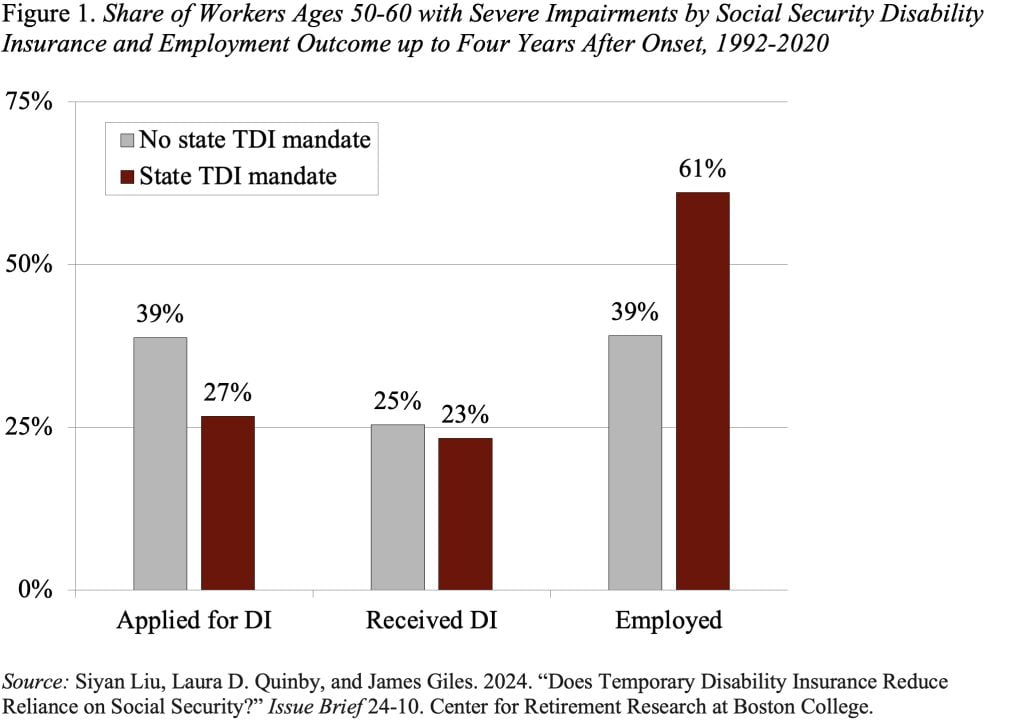

Impact of TDI for Those with Severe Disabilities

Up to four years after disability onset, 39 percent of potential DI applicants had submitted a claim for DI in non-mandate states, compared to only 27 percent in states with a TDI mandate (see Figure 1). This drop in applications, however, produces only a small decline in actual benefit receipt – suggesting that most of those no longer applying would likely not have qualified. In terms of employment – up to four years later, only 39 percent of potential DI applicants are employed in non-mandate states, compared to 61 percent in states with a TDI mandate. These findings seem to confirm that the drop in applications not only alleviates the administrative burden for the Social Security Administration, but also allows would-be applicants to continue working.

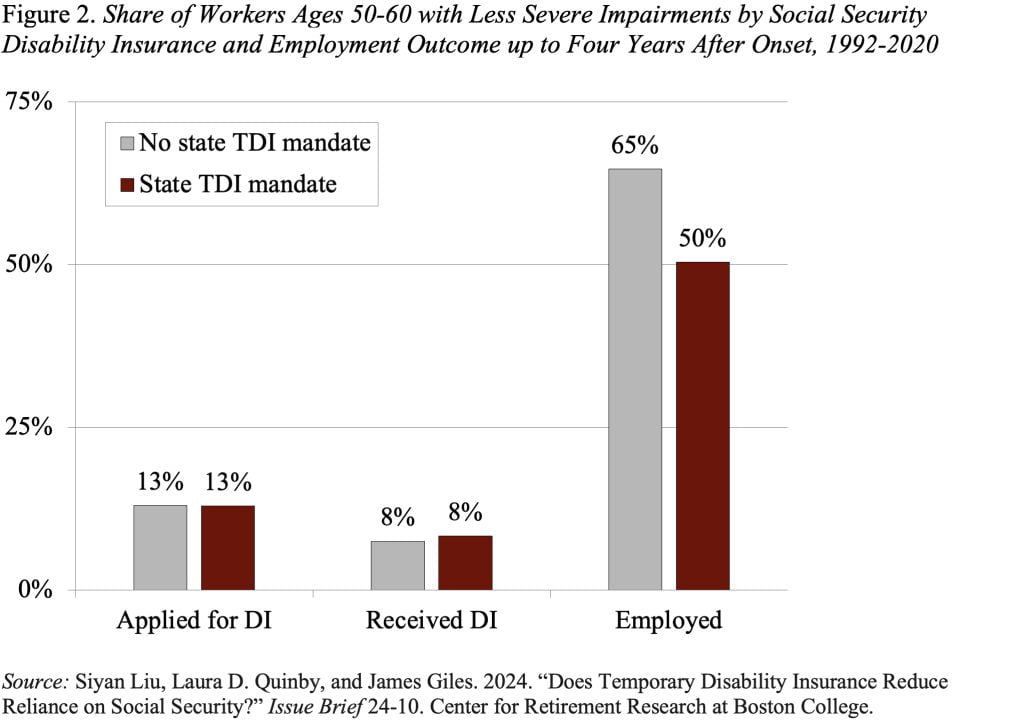

Impact of TDI for Workers with Less Severe Impairments

As expected, access to TDI has no impact on the share of workers with less severe impairments who apply for or receive DI (see Figure 2). However, TDI does seem to reduce employment. Whereas the employment rate was 65 percent in non-mandate states – up to four years after disability onset – it was only 50 percent in states with a TDI mandate.

This study should relieve concerns that expanding TDI will adversely affect Social Security DI. For those with severe disabilities, TDI appears to reduce the DI application rate a lot, the disability rolls a little, and increase employment up to four years after a health shock. For those with less severe conditions, TDI has no impact on DI applications or acceptances. The only somewhat worrying result is that TDI seems to lead to earlier retirement for those with less severe impairments.