Does Temporary Disability Insurance Reduce Reliance on Social Security?

The brief’s key findings are:

- Policymakers are increasingly interested in expanding access to paid leave, which includes temporary disability insurance (TDI).

- Advocates argue that TDI could reduce reliance on Social Security disability insurance (DI) by helping workers adjust to health shocks and return to work.

- Our results show that access to TDI reduces DI applications a lot, DI awards a little, and boosts employment for workers with severe disabilities.

- For those with less severe conditions, though, TDI seems to lead to earlier retirement.

Introduction

Temporary Disability Insurance (TDI) provides workers with income while they recover from a serious medical condition. Some argue that these benefits allow workers to adjust to health shocks and return to the workforce, reducing reliance on Social Security Disability Insurance (DI). Yet, TDI could also encourage workers to apply for DI benefits by providing a source of income during the lengthy qualification period, which would increase the program’s administrative burden and financial costs. Either way, spillovers from a national paid leave policy could be consequential for the DI program.

This brief, based on a recent paper, addresses two questions: 1) How does access to TDI benefits affect the likelihood that older workers with severe impairments apply for DI and end up receiving benefits? and 2) How does TDI affect employment for workers whose impairments are clearly not severe enough to qualify for DI?1Liu, Quinby, and Giles (2023).

The discussion proceeds as follows. The first section provides background on the current landscape of TDI benefits and the debate on potential spillovers to DI. The second section describes the data and methodology for the analysis. The third section presents the results. The final section concludes that expanding access to TDI would substantially decrease applications to the DI program, slightly decrease benefits receipt, and keep workers with severe impairments in the labor force. At the same time, TDI might create work disincentives for less vulnerable individuals.

Background

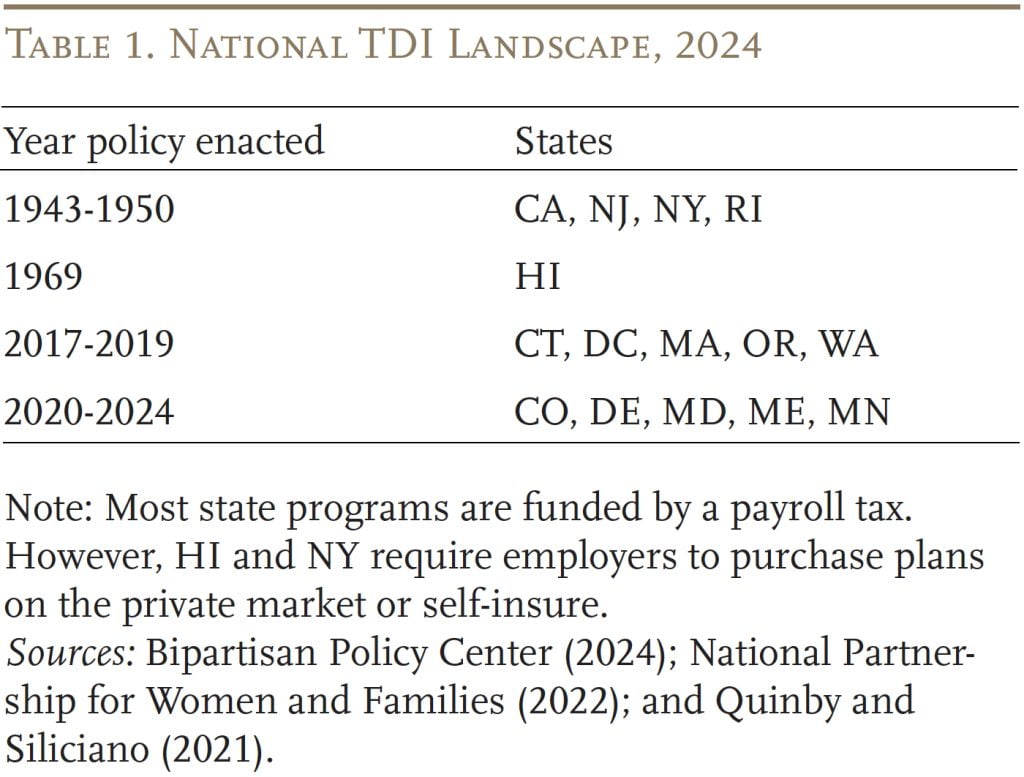

The national TDI landscape is a patchwork of state initiatives and employer-provided benefits. At the federal level, the Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 (FMLA) provides unpaid leave for a serious medical condition, but it does not replace lost earnings and, in practice, it covers less than 60 percent of the workforce.2Rossin-Slater and Stearns (2020). The FMLA requires employers with at least 50 employees to grant 12 weeks of unpaid leave to full-time workers with at least one year of tenure. Workers can access paid leave only if they reside in states with TDI mandates or if their employer voluntarily offers these benefits. Fifteen states – including many of the most populous – have enacted paid family and medical leave programs that include TDI as a component (see Table 1). State TDI programs typically provide workers with around 60 percent of pre-disability earnings for six months, although the duration of benefits varies greatly across states.3Bipartisan Policy Center (2024). Employer provision of TDI is relatively rare outside of the states with mandated benefits.4For example, 43 percent of the workforce had access to employer-sponsored TDI in 2022, but the share is only 34 percent in the South, where no state mandates TDI (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2022).

Support for establishing a federal paid leave program has also gained traction, sparking discussions of potential spillovers to Social Security’s DI program.5Most recently, the Biden Administration included paid leave in its Build Back Better plan of 2021. See Boyens, Smalligan, and Shabo (2022) for a discussion. Proponents of national paid leave argue that TDI would allow workers – particularly older workers who are most at risk – to adjust to health shocks and resume employment, reducing reliance on DI.6Autor and Duggan (2010). This mechanism is most salient when workers also have job protection, which reduces re-entry costs. Proponents also argue that experience-rating TDI premiums – as is done in some states and all employer plans – incentivizes employers to accommodate workers (Burkhauser and Daly 2011). However, some argue that experience-rating a mandated TDI benefit could discourage employers from hiring high-risk workers to begin with (Maestas 2019). However, others caution that TDI could instead serve as an on-ramp to DI: since TDI benefits are not considered earnings, they could provide needed income during the application process, encourage workers to apply, and ultimately increase the DI rolls.7Autor et al. (2013, 2015).

Complicating matters further, DI is designed for individuals with permanent and severe conditions that preclude them from participating in the labor market. Many workers with less severe impairments qualify for TDI but are unlikely to ever receive DI benefits. These individuals would likely keep working in some capacity unless TDI allowed them to take time out of the labor force. Policymakers considering a national program need to know how TDI impacts all workers who use the benefits, not just those who are DI-eligible.

Despite growing interest in TDI programs – and the clear potential for spillovers to DI – research is quite limited.8Autor et al. (2013) links state and industry-level variation in TDI access to DI caseloads at the state level. Autor, Duggan, and Gruber (2014) and Maestas, Mullen, and Strand (2013) provide more indirect evidence. See Quinby and Siliciano (2021) for a comprehensive literature review of the impact of paid leave on workers’ labor supply. Hence, the goal of this analysis is to examine how TDI impacts the decisions of workers with different levels of impairment.

Data and Methodology

The data for our analysis come from the 1992-2020 Health and Retirement Study (HRS), which collects information on workers’ health, employment, and DI status. Our sample is comprised of full-time workers ages 50-60 who experience a new work-limiting shock.9Our final sample includes 1,238 individuals with non-zero weights and non-missing information on job characteristics before disability onset. The analysis tracks these workers for two to four years after disability onset, allowing them ample time to submit a DI application.10Messel and Strand (2019) find that the median period from onset to application is 7.6 months using Social Security administrative data. However, final award decisions may require a longer processing time and applicants may wait up to five years (Autor et al. 2015). We consider workers by their access to TDI benefits; due to limited data on employer coverage, we compare workers residing in states with longstanding TDI mandates – California, New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island – with similar workers in other states.11For this analysis, states must have enacted their TDI policies before 2018, as we cannot yet track workers in states with more recent policies. Workers in states with mandated TDI and the other states have similar characteristics prior to disability onset (see Liu, Quinby, and Giles 2023).

The outcomes of interest are application for DI benefits, receipt of the benefits, and employment status. To measure the effects of TDI access, the analysis compares the outcomes of interest for workers with and without state-mandated TDI. Categorizing workers by the persistence and severity of their disabilities allows us to identify potential DI applicants, who account for 30 percent of our sample, as well as workers with less severe impairments who are unlikely to qualify for DI.12Specifically, we define potential DI applicants as those who expect their condition to persist beyond one year, and who either: 1) self-report being in poor health; 2) are newly diagnosed with a major health condition defined by Smith (2005); or 3) experience new difficulties with Activities of Daily Living or Instrumental Activities of Daily Living. See Liu, Quinby, and Giles (2023) for details.

Results

This section starts by examining how access to TDI affects DI applications and benefit receipt, as well as employment, for the potential DI applicant group. It then turns to the impact of TDI for those with less severe impairments.

Impact of TDI for Potential DI Applicants

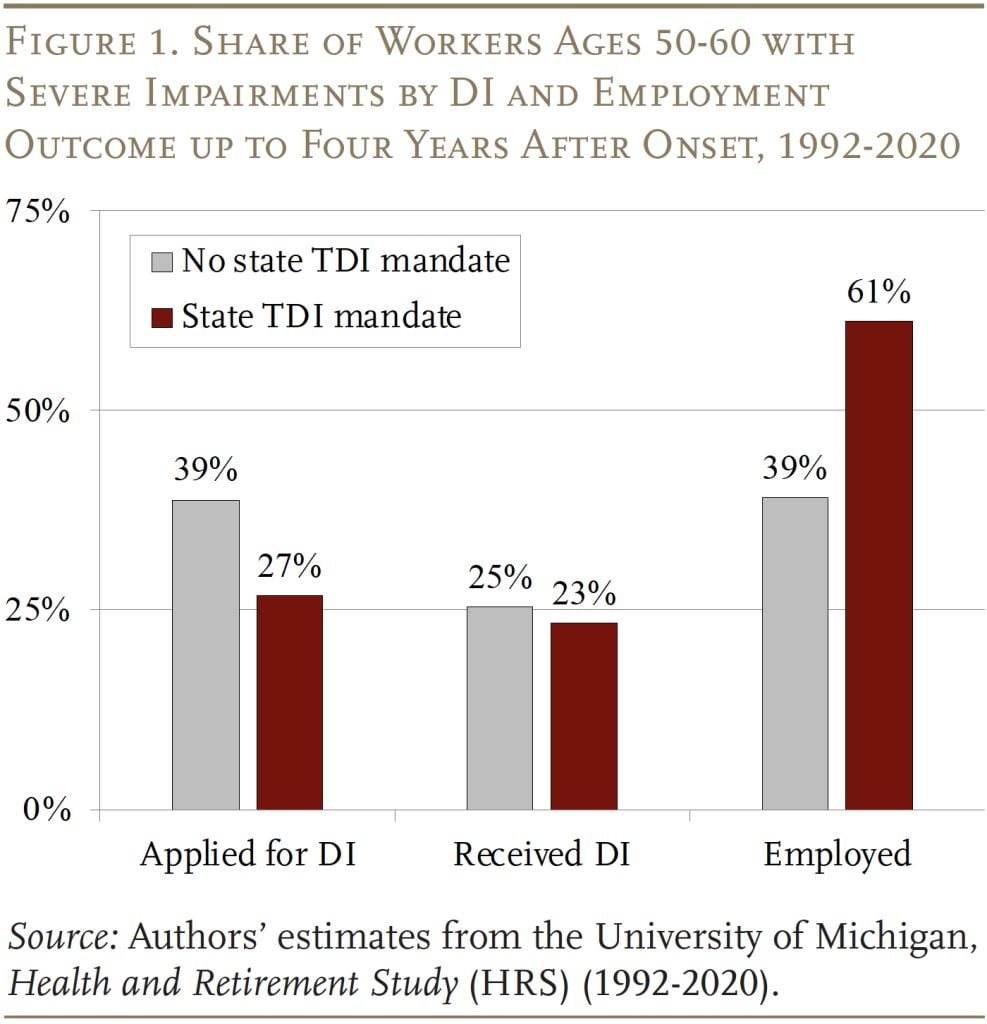

Up to four years after disability onset, 39 percent of potential DI applicants had submitted a claim for DI in non-mandate states, compared to only 27 percent in states with a mandate (see Figure 1). This drop in applications, however, produces only a small decline in actual benefit receipt – suggesting that most of those no longer applying would likely not have qualified.13The result on DI receipt is consistent with Maestas, Mullen, and Strand (2013), who find that marginal DI applicants are less likely to ultimately qualify, and their cases take longer as they go through appeal. We also see strong impacts on employment – up to four years later, only 39 percent of potential DI applicants are employed in non-mandate states, compared to 61 percent in states with a TDI mandate. The finding seems to confirm that the drop in applications not only alleviates the administrative burden for the Social Security Administration, but also allows would-be applicants to continue working.

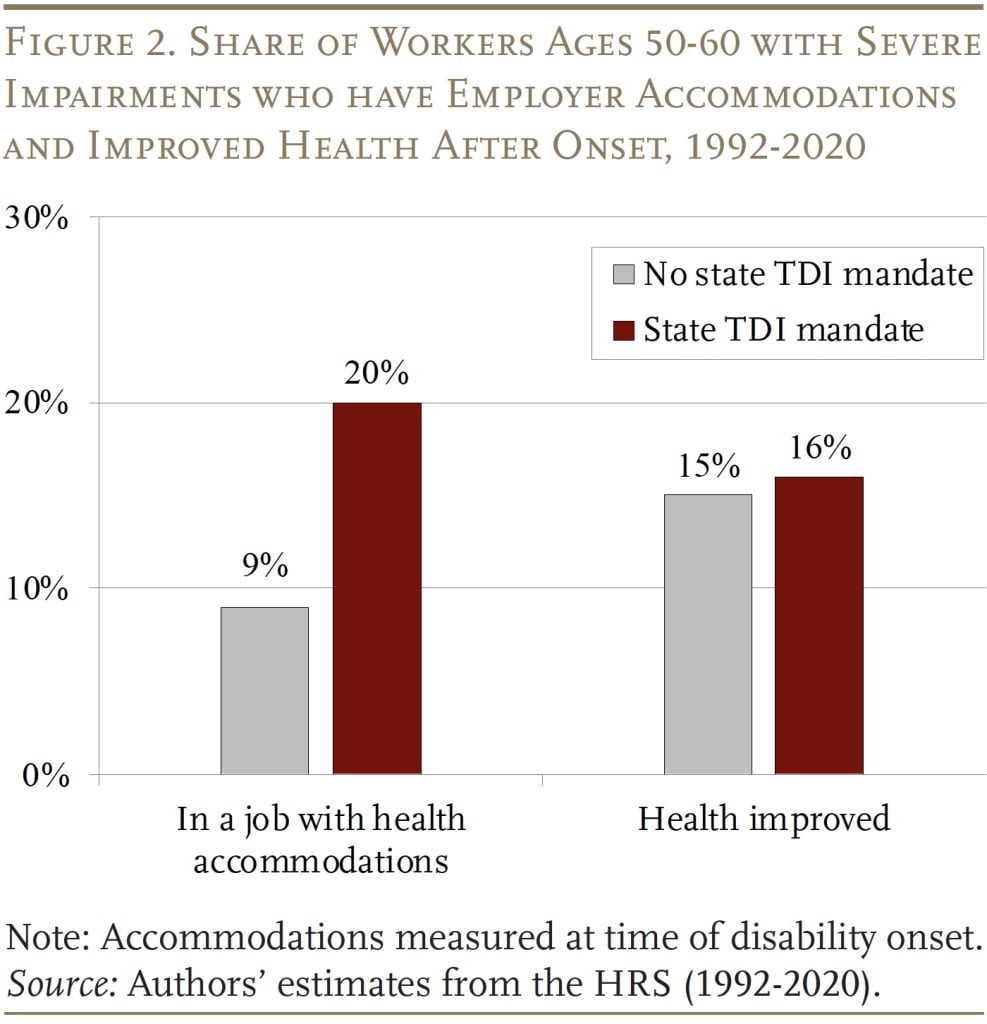

Potential DI applicants with access to TDI may work longer for a couple of reasons: 1) they may use their time on TDI to find a new job that matches their current capabilities; or 2) TDI may provide time to rest, recuperate, and allow them to return to their previous (or a similar) job. The evidence suggests that access to TDI increases the share of people receiving employer accommodations by 11 percentage points, but has virtually no impact on self-reported health in the short run (see Figure 2). The improvement in accommodations could come from either potential DI applicants using their time on TDI to find a job with such supports or employers being more accommodating of existing workers.14Employers have a financial incentive to be more accommodating if they are in a state that requires experience-rating of TDI premiums. The sample is too small to differentiate between these two mechanisms.

Impact of TDI for Workers with Less Severe Impairments

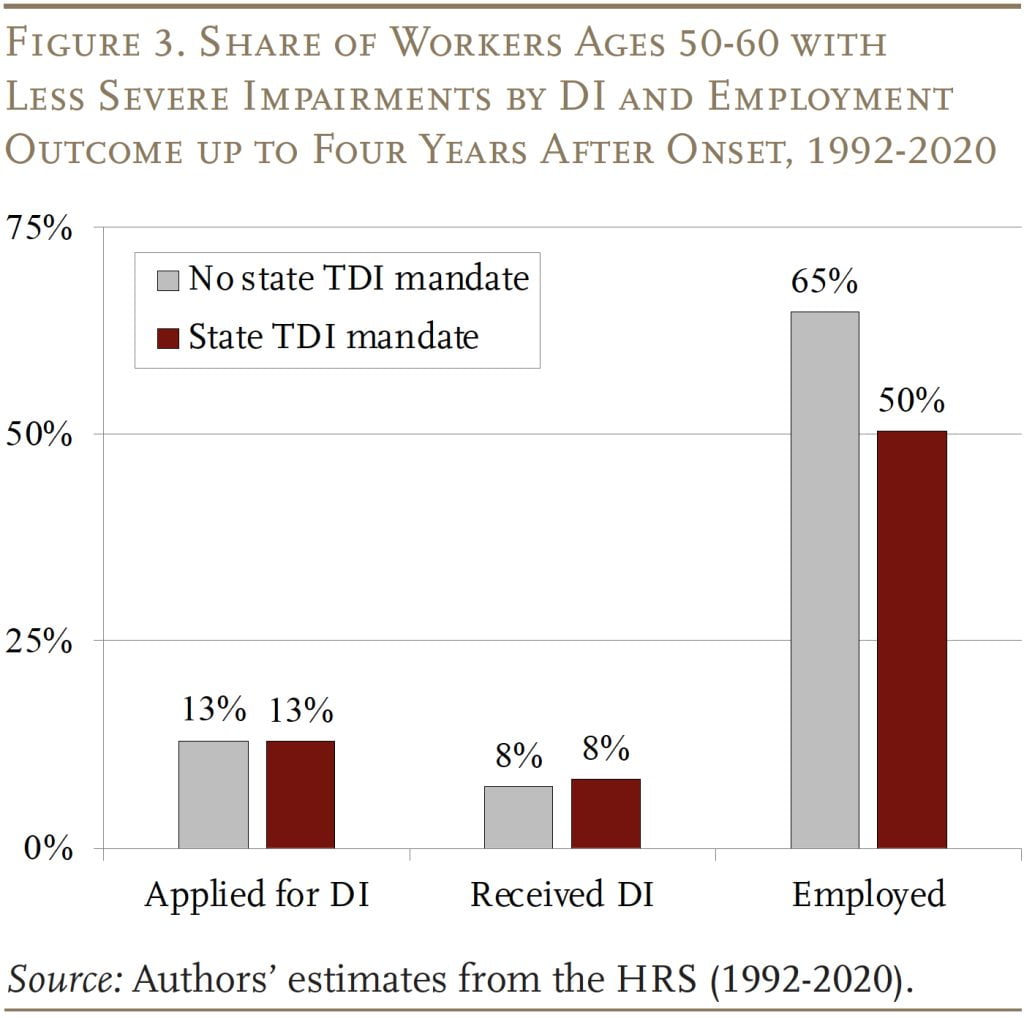

As expected, access to TDI has no impact on the share of workers with less severe impairments who apply for or receive DI (see Figure 3). However, TDI does seem to reduce employment. Whereas the employment rate was 65 percent in non-mandate states – up to four years after disability onset – it was only 50 percent in states with a TDI mandate.

Conclusion

Policymakers at the state and federal levels are increasingly focused on expanding access to paid leave. Advocates argue that providing medical leave to older workers (TDI) may reduce their reliance on the federal DI program and keep them in the labor force. This brief finds that access to TDI does both: reducing the DI application rate and increasing employment up to four years after a health shock for workers with severe disabilities. These responses also result in a small decline in the disability rolls. On the other hand, for those with less severe conditions, who are unlikely to qualify for DI, TDI seems to lead to earlier retirement.

References

Autor, David and Mark Duggan. 2010. “Supporting Work: A Proposal for Modernizing the U.S. Disability Insurance System.” Washington, DC: The Center for American Progress and the Hamilton Project.

Autor, David, Mark Duggan, Jonathan Gruber, and Catherine Maclean. 2013. “How Does Access to Short Term Disability Insurance Impact SSDI Claiming?” Working Paper DRC NB13-09. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Autor, David, Mark Duggan, and Jonathan Gruber. 2014. “Moral Hazard and Claims Deterrence in Private Disability Insurance.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 6(4): 110-141.

Autor, David H., Nicole Maestas, Kathleen J. Mullen, and Alexander Strand. 2015. “Does Delay Cause Decay? The Effect of Administrative Decision Time on the Labor Force Participation and Earnings of Disability Applicants.” Working Paper w20840. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Bipartisan Policy Center. 2024. “State Paid Family Leave Laws Across the U.S.” Explainer. Washington, DC.

Boyens, Chantel, Jack Smalligan, and Vicki Shabo. 2022. “Evolution of Federal Paid Family and Medical Leave Policy.” Issue Brief. Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

Burkhauser, Richard V. and Mary Daly. 2011. “The Declining Work and Welfare of People with Disabilities: What Went Wrong and a Strategy for Change.” Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute.

Liu, Siyan, Laura D. Quinby, and James Giles. 2023. “Does Temporary Disability Insurance Reduce Older Workers’ Reliance on Social Security Disability Insurance?” Working Paper 2023-13. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Maestas, Nicole, Kathleen Mullen, and Alexander Strand. 2013. “Does Disability Insurance Receipt Discourage Work? Using Examiner Assignment to Estimate Causal Effects of SSDI Receipt.” American Economic Review 103(5): 1797-1829.

Maestas, Nicole. 2019. “Identifying Work Capacity and Promoting Work: A Strategy for Modernizing the SSDI Program.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 686(1): 93-120.

Messel, Matt and Alexander Strand. 2019. “The Time between Disability Onset and Application for Benefits: How Variation among Disabled Workers May Inform Early Intervention Policies.” Social Security Bulletin 79(3): 47-61.

National Partnership for Women and Families. 2022. “State Paid Family and Medical Leave Insurance Laws.” Washington, DC.

Rossin-Slater, Maya and Jenna Stearns. 2020. “The Economic Imperative of Enacting Paid Family Leave across the United States.” Washington, DC: Washington Center for Equitable Growth.

Quinby, Laura D. and Robert L. Siliciano. 2021. “Implications of Allowing U.S. Employers to Opt Out of a Payroll-Tax-Financed Paid Leave Program.” Special Report. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Smith, James P. 2005. “Consequences and Predictors of New Health Events.” In Analysis in the Economics of Aging, edited by D. A. Wise, 213-240. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

University of Michigan. Health and Retirement Study, 1992-2020. Ann Arbor, MI.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2022. National Compensation Survey: Employee Benefits in the United States, March 2022. Washington, DC.i

Endnotes

- 1Liu, Quinby, and Giles (2023).

- 2Rossin-Slater and Stearns (2020). The FMLA requires employers with at least 50 employees to grant 12 weeks of unpaid leave to full-time workers with at least one year of tenure.

- 3Bipartisan Policy Center (2024).

- 4For example, 43 percent of the workforce had access to employer-sponsored TDI in 2022, but the share is only 34 percent in the South, where no state mandates TDI (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2022).

- 5Most recently, the Biden Administration included paid leave in its Build Back Better plan of 2021. See Boyens, Smalligan, and Shabo (2022) for a discussion.

- 6Autor and Duggan (2010). This mechanism is most salient when workers also have job protection, which reduces re-entry costs. Proponents also argue that experience-rating TDI premiums – as is done in some states and all employer plans – incentivizes employers to accommodate workers (Burkhauser and Daly 2011). However, some argue that experience-rating a mandated TDI benefit could discourage employers from hiring high-risk workers to begin with (Maestas 2019).

- 7Autor et al. (2013, 2015).

- 8Autor et al. (2013) links state and industry-level variation in TDI access to DI caseloads at the state level. Autor, Duggan, and Gruber (2014) and Maestas, Mullen, and Strand (2013) provide more indirect evidence. See Quinby and Siliciano (2021) for a comprehensive literature review of the impact of paid leave on workers’ labor supply.

- 9Our final sample includes 1,238 individuals with non-zero weights and non-missing information on job characteristics before disability onset.

- 10Messel and Strand (2019) find that the median period from onset to application is 7.6 months using Social Security administrative data. However, final award decisions may require a longer processing time and applicants may wait up to five years (Autor et al. 2015).

- 11For this analysis, states must have enacted their TDI policies before 2018, as we cannot yet track workers in states with more recent policies. Workers in states with mandated TDI and the other states have similar characteristics prior to disability onset (see Liu, Quinby, and Giles 2023).

- 12Specifically, we define potential DI applicants as those who expect their condition to persist beyond one year, and who either: 1) self-report being in poor health; 2) are newly diagnosed with a major health condition defined by Smith (2005); or 3) experience new difficulties with Activities of Daily Living or Instrumental Activities of Daily Living. See Liu, Quinby, and Giles (2023) for details.

- 13The result on DI receipt is consistent with Maestas, Mullen, and Strand (2013), who find that marginal DI applicants are less likely to ultimately qualify, and their cases take longer as they go through appeal.

- 14Employers have a financial incentive to be more accommodating if they are in a state that requires experience-rating of TDI premiums.