Households’ Plan for Long-Term Care Often Do Not Reflect Reality

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

For those who start with $100,000, Medicaid is not an easy option.

As part of an extended study on the risks faced by households approaching retirement, we just completed a project that focused on the risks associated with medical and long-term care costs.

As it turns out, while medical risks are highly uncertain and potentially expensive, much of these risks are insured by Medicare (and Medicaid for those eligible for both programs). Long-term care risks, in contrast, are not well insured. Only 3 percent of all U.S. adults or 15 percent of those ages 65+ have long-term care insurance. And a major finding was that people had little idea of the likelihood of needing long-term care or of the potential costs of that care.

The implications of households underestimating their healthcare risks are that they may not plan well to protect themselves against these risks. Without the appropriate insurance or resources, older households may have to make substantial adjustments or consider less-preferred options. The question is, how realistic are those contingency plans?

The analysis was based on a 2024 Greenwald Research online survey of 508 individuals ages 48-78 with at least $100,000 in investable assets. The survey included a question regarding what contingency plans respondents would consider if they could not afford their medical or long-term care expenses. These contingency plans were then compared to reality using data from the Health and Retirement Study – a nationally representative sample of those over age 50 who are interviewed every two years.

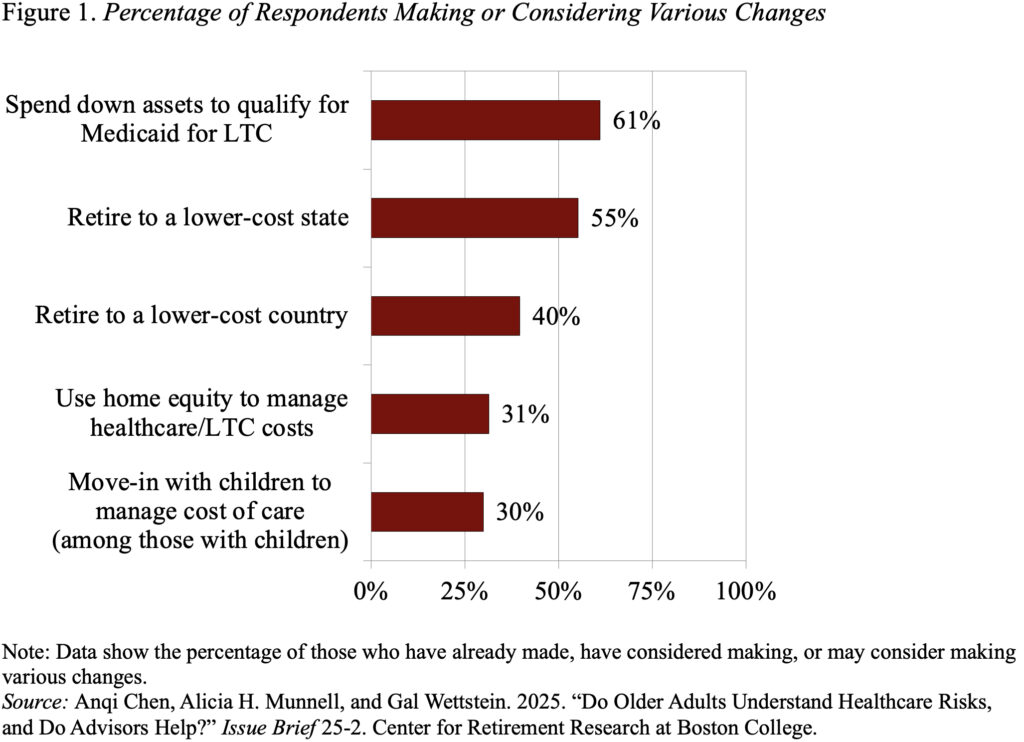

Interestingly, about 60 percent of survey respondents said they would consider spending down to Medicaid, while only 30 percent said they would consider using their home equity or moving in with their children (see Figure 1). However, many of these preferences may not be realistic.

Many older households who believe they can always fall back on Medicaid may not realize that the program’s income and asset limits require impoverishment. In 2025, the monthly income limit for Medicaid eligibility for those over age 65 is typically around $2,800 ($5,600 for couples) and the asset limit is typically $2,000 ($3,000 for couples), but varies by state.

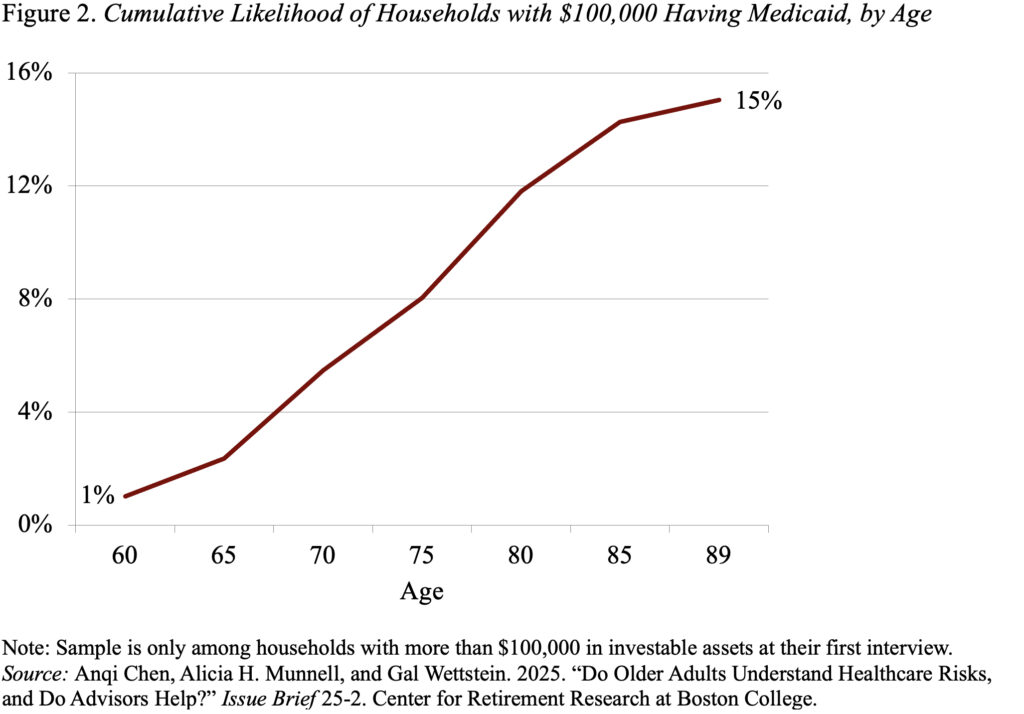

Among households with more than $100,000 in investable assets, like those in our survey, almost none would qualify based on the standard income rules because their Social Security benefit and defined benefit income would put them above the limit. Several states have special income rules for long-term care with slightly higher limits. Even then, 70 percent of households in our sample would not qualify. In reality, only 15 percent of households with more than $100,000 in initial assets will actually end up on Medicaid (see Figure 2), compared to the 60 percent of households who think that spending down to Medicaid is an option for them.

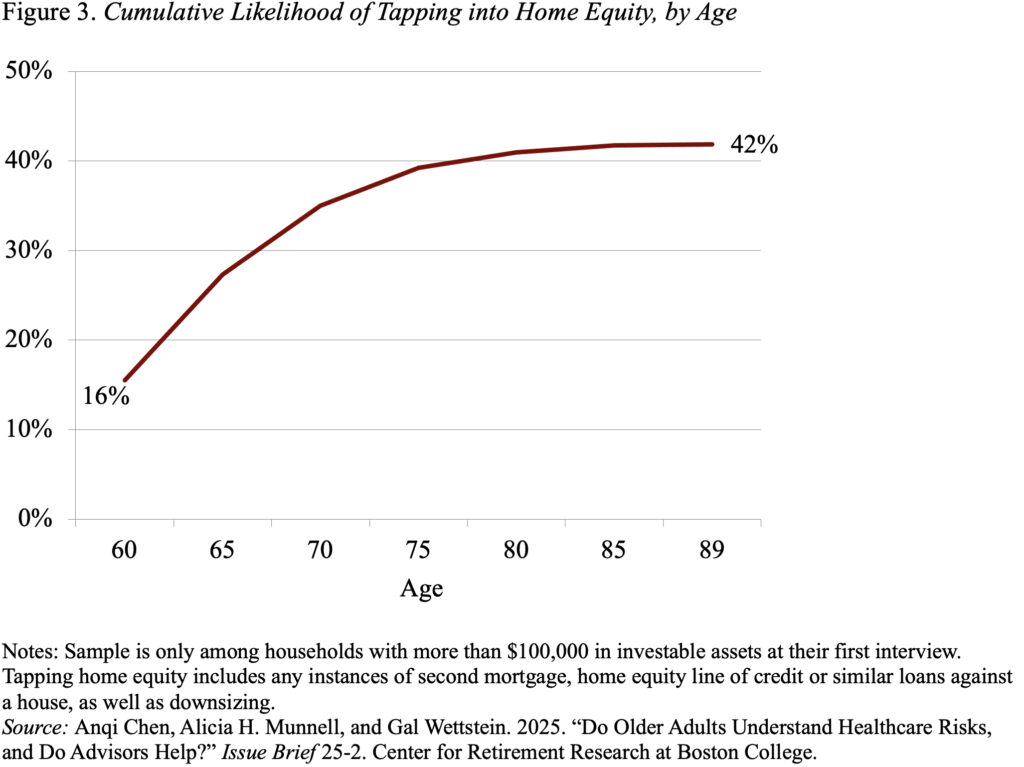

One of the least popular contingency options for financing healthcare costs is tapping home equity. Less than a third of households said they would consider it. However, in reality, over 40 percent will tap home equity in retirement – either by getting a second mortgage, applying for a home equity line of credit or other loans against the house, or downsizing and moving to a less valuable house (see Figure 3).

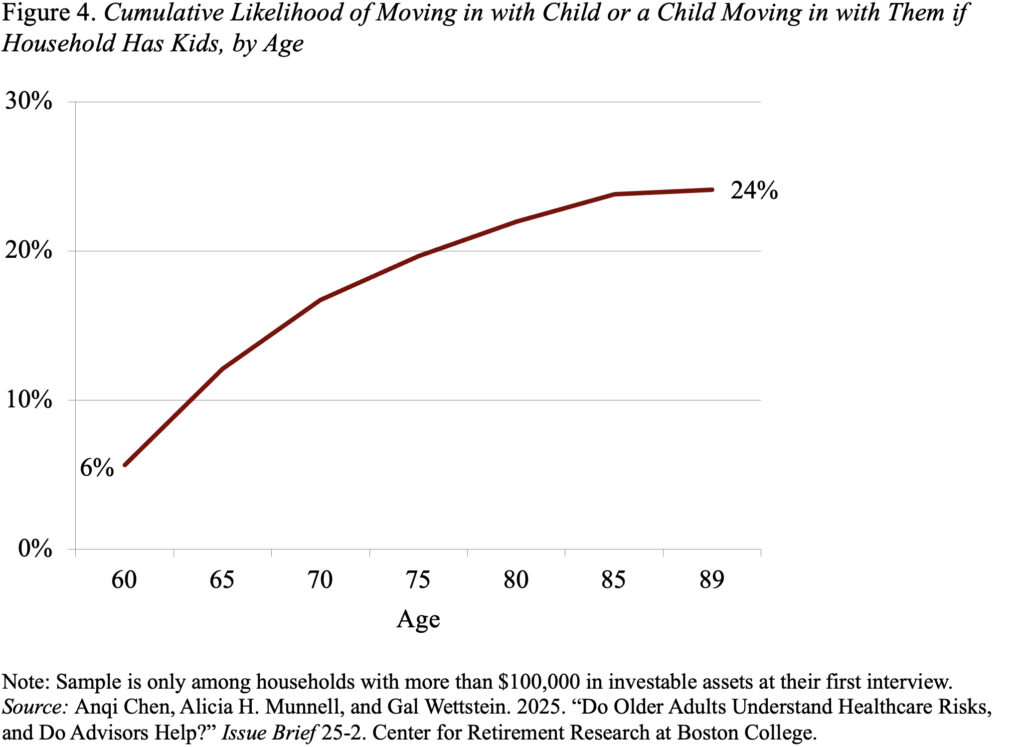

Finally, another unpopular option for managing healthcare needs among respondents is moving in with children. Again, less than a third say they would consider this option. Interestingly, in the real world, only about a quarter of older households in our wealth group end up living with their children (see Figure 4). So, this option does seem like the least preferred back-up if plans fail.

In short, the uninsured components of healthcare costs in retirement – particularly those associated with long-term care – can be substantial, and older households do not have an accurate perception of these risks. As a result, many will end up with inadequate resources. When participants in our survey – individuals having $100,000 or more in investable assets – were asked how they would deal with such a situation, about 60 percent said they would spend down to qualify for Medicaid. That is not a reasonable option for most given the program’s tight income and asset requirements. In fact, only 15 percent of this group is ever likely to qualify for Medicaid. Respondents were less enthusiastic about tapping their home equity, but many (over 40 percent), in fact, do tap home equity as a source of support.