How Are People Going to Pay for Long-Term Care?

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

An aging population will put pressure on Medicaid.

Although immediate Medicaid cuts are off the table with the failed effort to repeal and replace Obamacare, the basic economics underlying the Medicaid program have not changed.

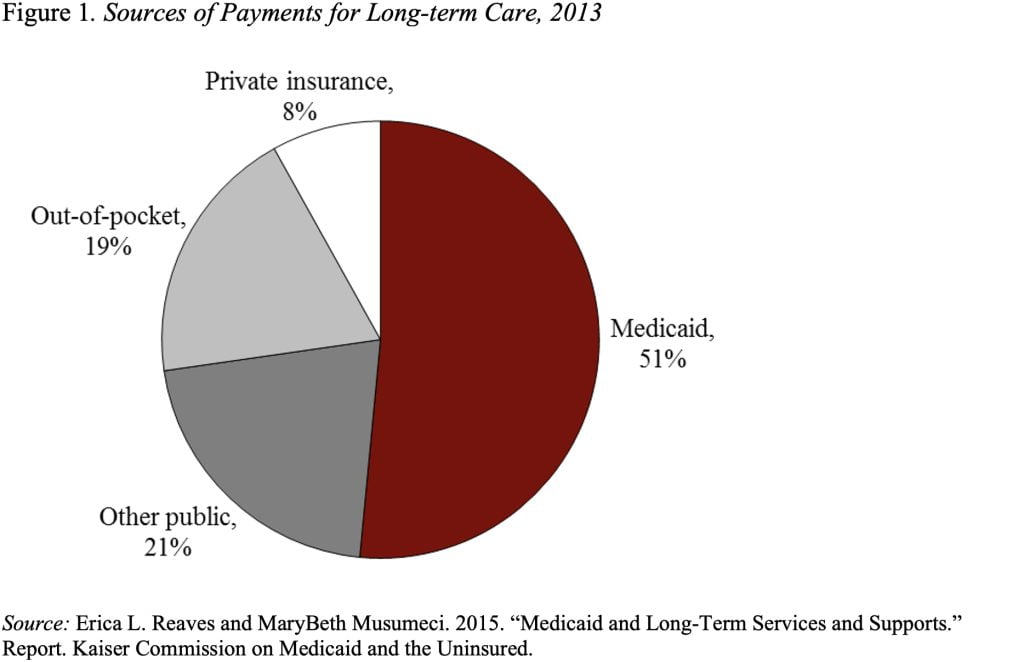

Medicaid currently pays for more than half of long-term care expenses (see Figure 1). This outcome reflects the fact that older people exhaust their assets and turn to Medicaid to cover their nursing home and other forms of long-term care. Under current Medicaid arrangements, the federal government match is dollar-for-dollar in wealthy states; the federal match can approach three to one in poorer states.

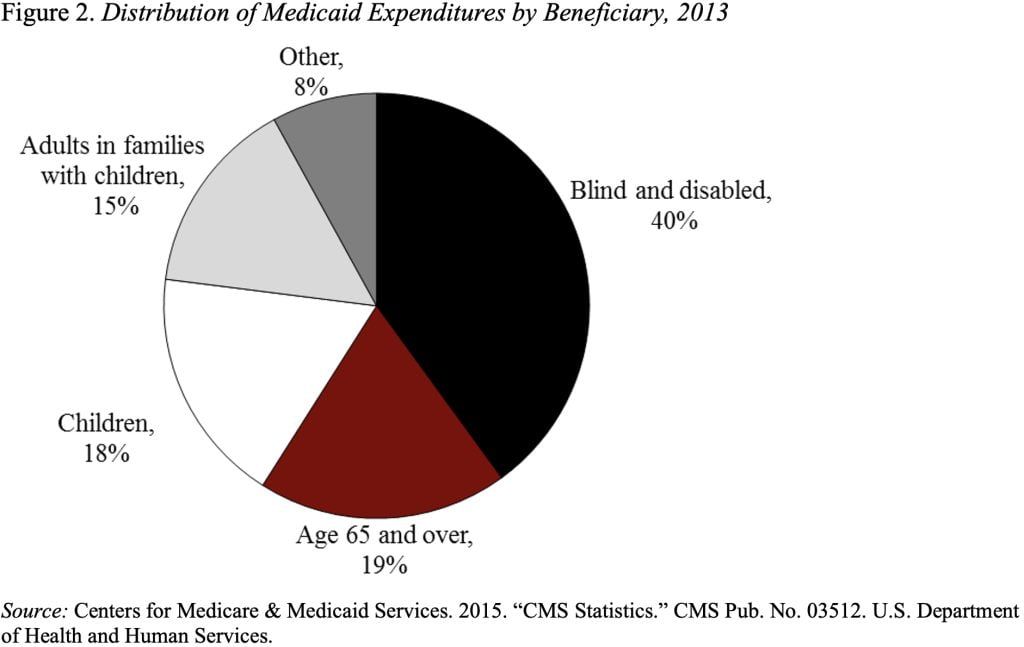

We know for sure that as the population ages, the demand for long-term care will increase. This increase in costs will put pressure on both the states and the federal government. They can both respond with allocating more of their budgets to Medicaid. Or they can reallocate money away from the old to other types of Medicaid beneficiaries (see Figure 2).

If Medicaid is going to pay less, one might ask if people will be more likely to buy long-term care insurance. Long-term care insurance has never been a particularly popular product – due to high premiums, the risk of lapsing, and the availability of Medicaid. But now it appears that companies don’t like the product any more than the public. In 2016, the National Association of Insurance Commissioners showed 50 companies with more than 10,000 policies outstanding. But in 2017 only 10 companies are issuing a meaningful number of new policies.

Today, the United States has 12 million people ages 80 or older. In 2035, that number is projected to be 24 million. That means that the number of nursing home beds will need to double – from the 1.7 million (where it has been for some time) to 3.4 million. How are we going to pay for all this?