How Much Do People Value Annuities and Their Added Features?

The brief’s key findings are:

- While annuities offer retirees a reliable stream of lifetime income, few people purchase them.

- To probe people’s perceptions of annuities, a new survey queried those near or in retirement with over $100,000 in financial assets.

- About half of respondents say they would be willing to buy an annuity at prevailing market rates, while just 12 percent actually do so.

- The study tested whether low annuity take-up could be explained by a lack of liquidity or the inability to make bequests, but found no such evidence.

- In short, people may be deterred not by a lack of interest in annuities but by a lack of knowledge of the product and how to buy it.

Introduction

Although many economic models predict high annuitization rates, only a small portion of retirees hold an annuity. This discrepancy is known as the “annuity puzzle.” Many explanations have been advanced for this puzzle, all of them promoting reasons why individuals might not want to annuitize.

This brief, which is based on a recent paper, analyzes a new survey of individuals near or in retirement with over $100,000 of investable assets.1Arapakis and Wettstein (2023a). The findings suggest that roughly half of this population want to buy an annuity at prevailing market prices – significantly more than the 12 percent that actually do so. Further, they suggest that potentially aversive qualities of annuities, such as the fact that they cannot be bequeathed or that they tie up wealth in an illiquid form, have a negligible impact on the respondents’ willingness to annuitize.

The rest of the brief is structured as follows. The first section briefly discusses the background of the annuity puzzle. The second section describes the survey. The third section presents the results. The final section concludes that many more individuals are willing to buy annuities than actually buy them, suggesting that logistical impediments stymie more widespread annuitization.

Background

The annuity puzzle is a longstanding question. Since 1965, economists have argued that many individuals should annuitize at least some of their wealth in retirement.2Yaari (1965). However, in the biennial Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a nationally representative survey of Americans over age 50 conducted by the University of Michigan, only 12 percent of households with financial assets over $100,000 receive any annuity income.3Although wealth is endogenous (i.e., buying an annuity reduces wealth), individuals with less than $100,000 of financial assets annuitize less, with approximately 7 percent of the under $100,000 population receiving annuity income.

Existing Explanations for Annuity Puzzle

Researchers have offered many potential rationales for the annuity puzzle. A leading explanation is that annuities are too expensive.4Mitchell et al. (1999) and Wettstein et al. (2021). One reason for high costs is adverse selection – that longer-lived individuals are more likely to buy annuities in the first place, leading providers to raise prices. Insurance companies also have administrative costs and seek to make profits. A second explanation for the annuity puzzle is that people may want to bequeath their assets – making annuities without survivor benefits unattractive. A third explanation is that people may worry about annuities being illiquid, thus making individuals unable to pay for large unexpected expenses, such as costly nursing home stays.5See Hubbard and Judd (1987) and Laitner, Silverman, and Stolyarov (2018).

A recent review of the literature also documented a few other prominent explanations for the annuity puzzle.6Arapakis and Wettstein (2023a). What all the explanations have in common is that they suggest reasons why individuals might not want to annuitize, for “good” reasons (e.g., because Social Security provides sufficient lifetime income)7Bernheim (1991); Pashchenko (2013); and Hosseini (2015). or for “bad” reasons (such as individuals mistakenly believing they are unlikely to live very long).8O’Dea and Sturrock (2023) and Arapakis and Wettstein (2023b).

Financial Literacy and Channel Factors

Looking beyond why individuals might not want to annuitize, other factors could lead to low annuitization rates even if individuals would be inclined to buy an annuity if offered one. For example, some individuals might not know that annuities exist, or they might not understand them.9Lusardi and Mitchell (2014). Further, even if individuals are interested in annuities, they might not know how to buy them.

In particular, social psychology has long recognized “channel factors:” seemingly small characteristics of a situation that can have far-reaching consequences for the ability of individuals to follow through on their intentions. For example, a classic experiment found that giving students information on the importance of tetanus vaccines produced the intention to be inoculated. However, only a group of students who were given concrete plans for receiving the shot ended up getting vaccinated.10Leventhal, Singer, and Jones (1965). This result, replicated many times since, led to the conclusion that intentions are insufficient to produce action on their own, but rather require specific step-by-step plans.11For example, see Gollwitzer (1999).

In the context of annuities, this finding implies that wanting to buy an annuity is meaningfully removed from actually buying one. The results of the new survey and its randomized control trial described next are consistent with this social psychology intuition.

Survey and Randomized Control Trial

The survey, conducted by Greenwald Research in June of 2023, questioned 1,216 individuals. Participants were ages 55-95 and had over $100,000 in savings, excluding real estate, defined benefit pension plans, and the value of any business. Among other things, the survey probed respondents’ demographic and economic characteristics, their sentiments regarding annuities, and their longevity expectations.

The core of the analysis relies on a randomized control trial (RCT) with a control group and two treatment groups. In the control group, the trial elicited each consumer’s minimum annual lifetime annuity payment at which they would buy an annuity for a $100,000 premium. In Treatment Group 1, consumers were offered the same annuity as in the control group but, in this case, the annuity had an added early death bequest feature: if the payouts by the time of death had not exhausted the premium, the balance would be paid out to the decedent’s heirs. In Treatment Group 2, consumers were offered the same annuity as in the control group but, in this case, the annuity had an added liquidity feature: where annuity holders could break the contract and withdraw the remaining premium.

Results

The survey includes both direct questions about how respondents feel towards guaranteed lifetime income in general, as well as an RCT designed to elicit valuations of standard immediate annuities, on the one hand, and the two variations of annuities, on the other. This section presents the three sets of results.

Direct Questions on Guaranteed Lifetime Income Sentiments

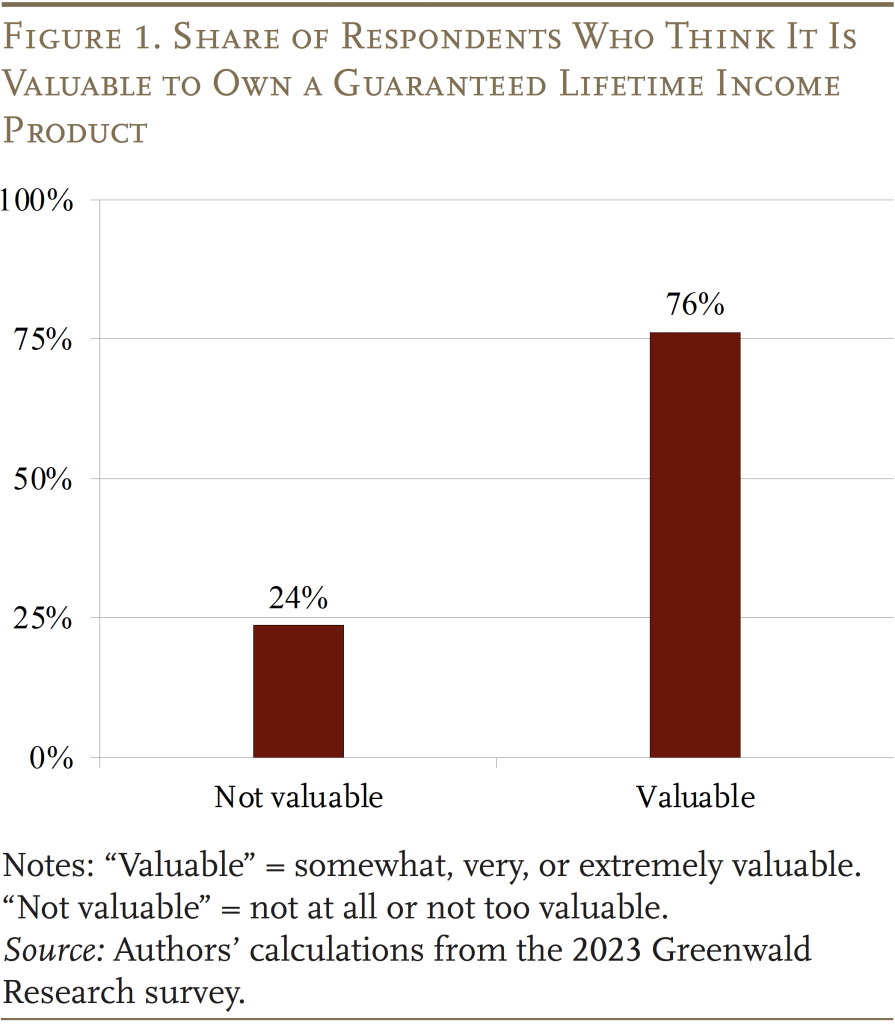

The survey asks respondents directly how they feel about annuities. Figure 1 shows that 76 percent say it is at least somewhat valuable.

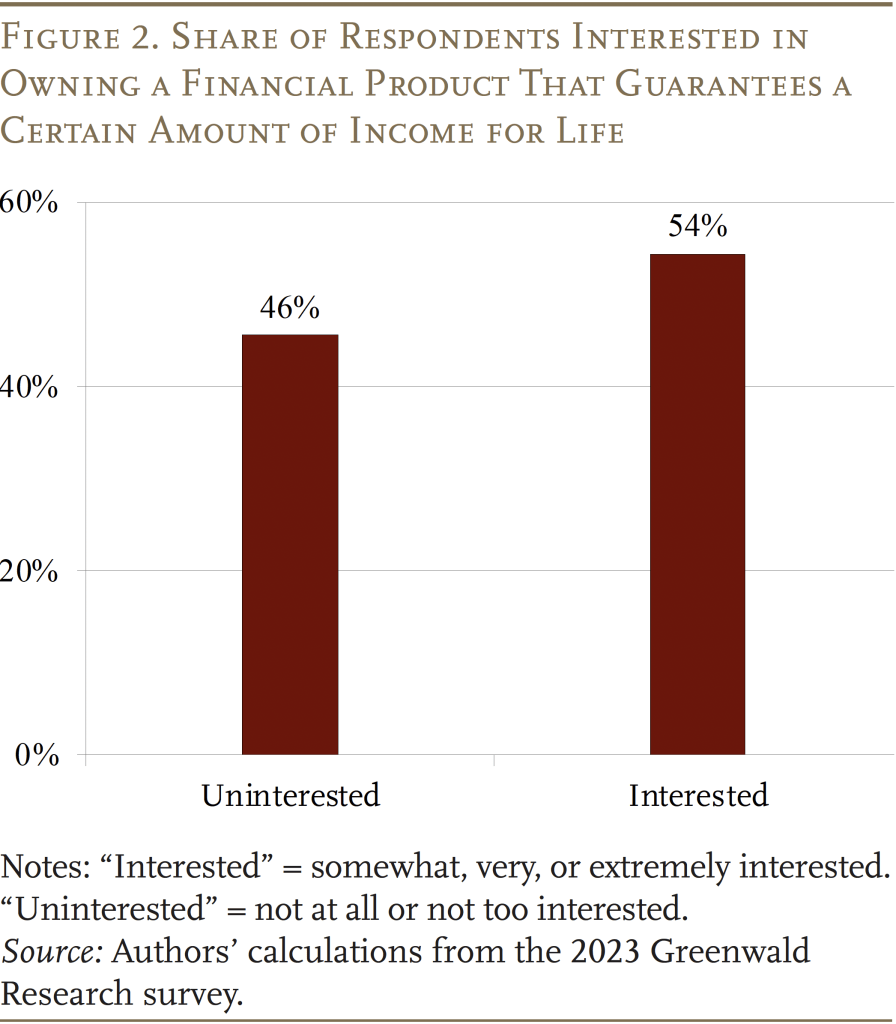

Further, of those who do not currently own an annuity, most say they are at least somewhat interested in owning one (see Figure 2).1213.6 percent of respondents already owned an annuity, a share similar to that found in the HRS for a similar population.

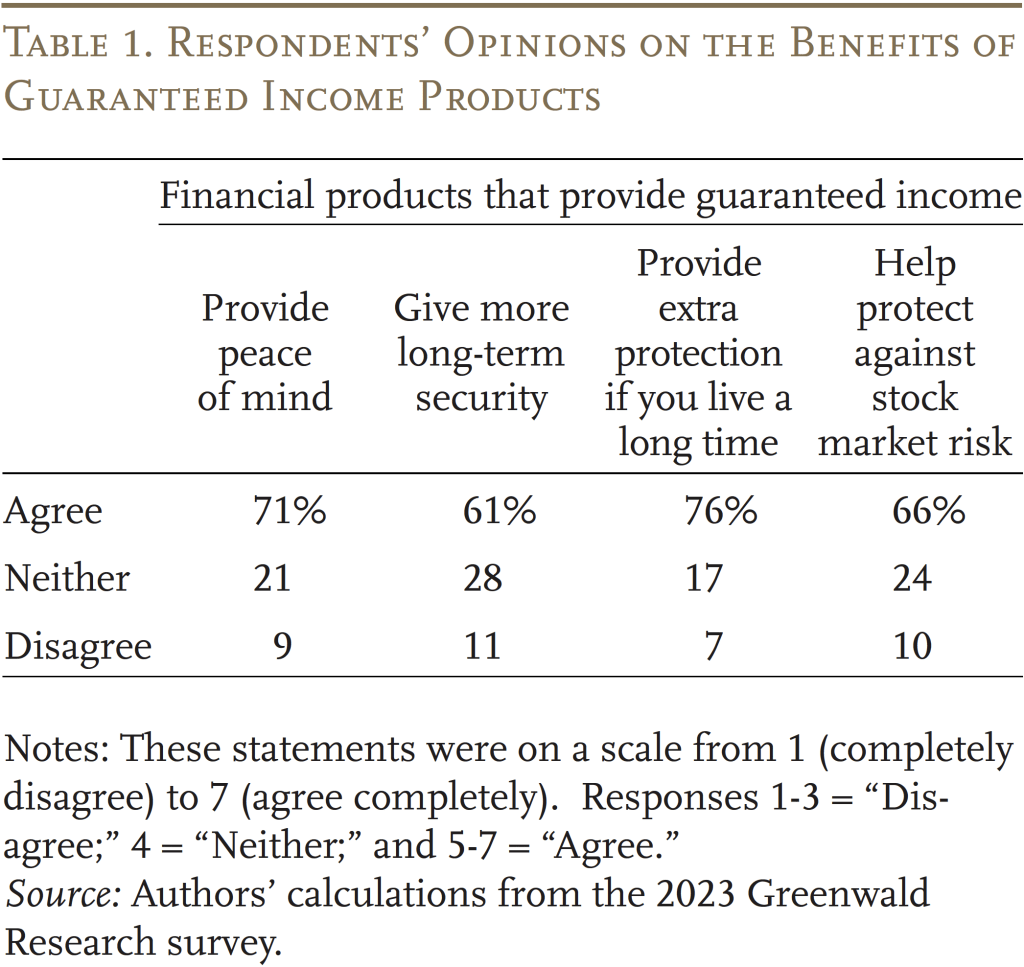

Respondents also generally agree that guaranteed lifetime income would provide emotional and insurance benefits (see Table 1).

Direct questions about annuities in the abstract, however, cannot determine why those who do not value annuities feel that way. In particular, respondents may think annuities are good but not worth their cost, one of the main explanations of the annuity puzzle. Or, they may like the idea of an annuity but feel its benefits are outweighed by its costs in terms of foregone bequests or liquidity. The RCT section of the survey explores these issues further.

Immediate Annuity Valuations

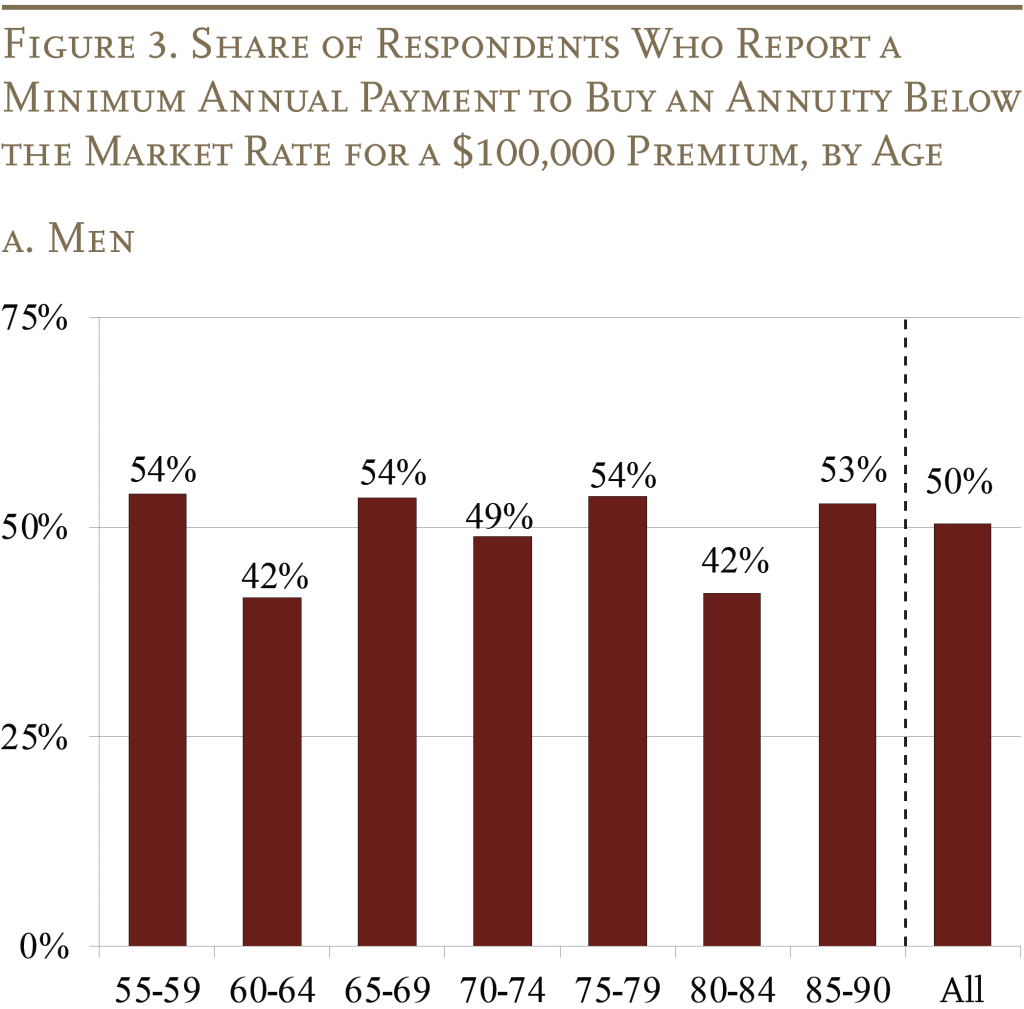

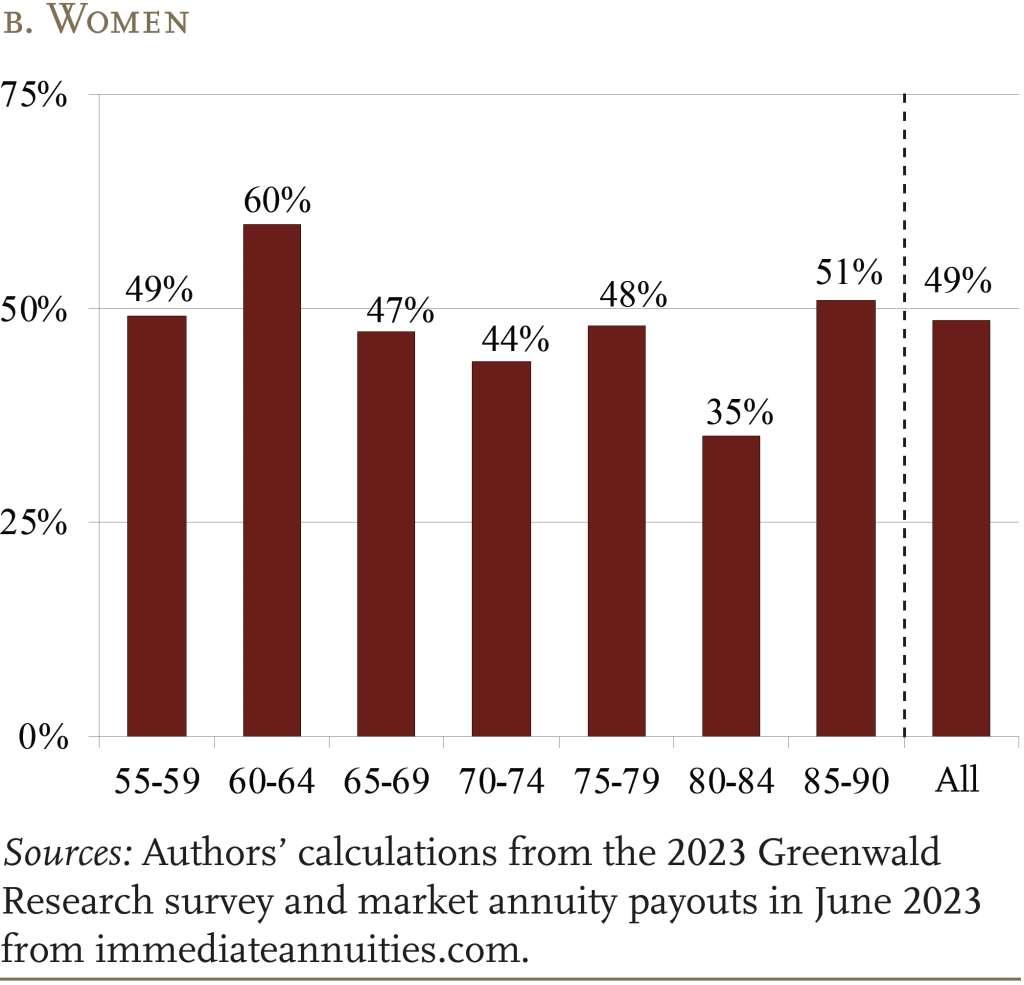

The RCT elicited from each respondent how much guaranteed monthly income they would require in order to be willing to pay a $100,000 premium. Roughly half of respondents’ required payments were lower than the payments they could have gotten from annuities sold on the market to customers with their own age and gender at the time the survey was fielded.13In the United States, annuities are generally priced only based on gender, age, and state of residence. Figures 3a and 3b show this result by age group, for men and women respectively.

The 50-percent share of respondents willing to buy annuities at prevailing market rates far exceeds the share of respondents who actually have an annuity (13.5 percent) or the share of similar individuals in larger surveys with over $100,000 in financial assets (12 percent). Thus, the results suggest that a large swath of the population with assets sufficient to buy an annuity also want to buy an annuity, yet do not follow through on that desire. This finding contrasts with all the explanations of the annuity puzzle that rely on rationales for why individuals do not want to annuitize. Instead, the results suggest that some logistical impediment such as channel factors is preventing more widespread annuitization, rather than the aversive quality of annuities themselves.

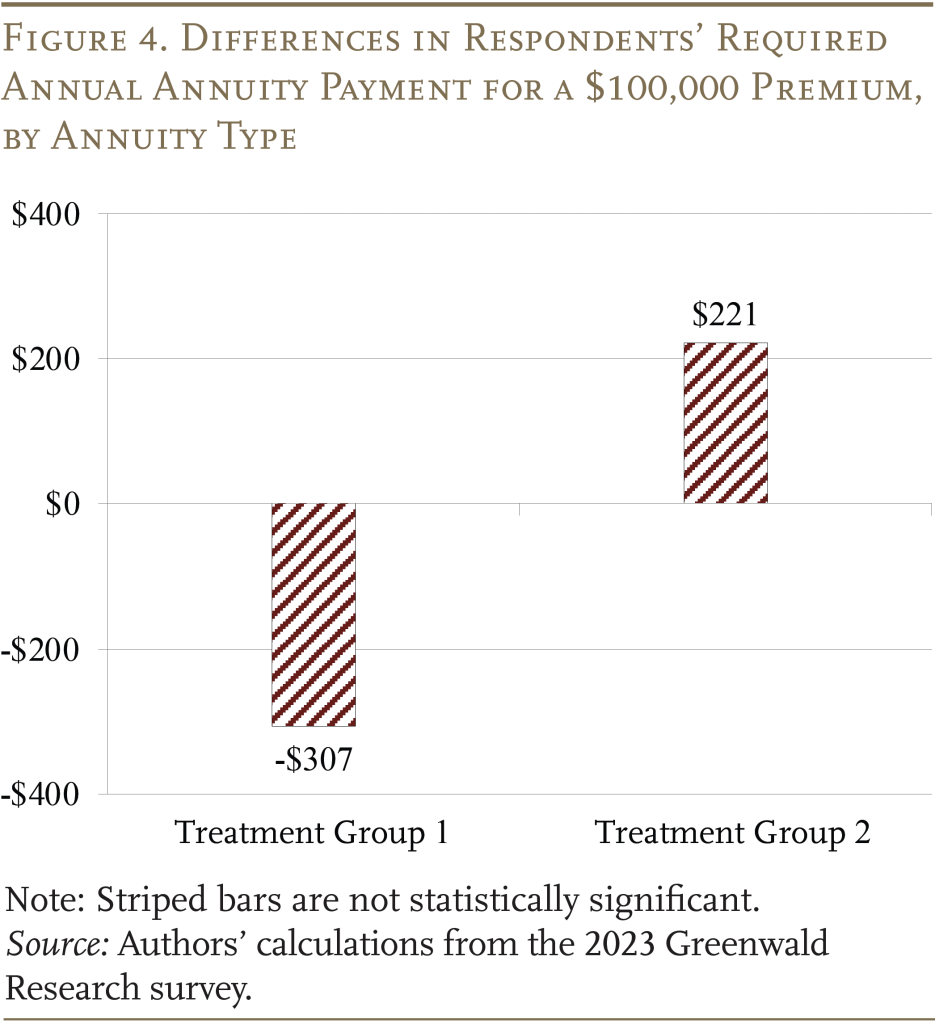

Difference in Valuations for Different Annuity Types

The results of the RCT regarding different types of immediate annuities also support the notion that it is not aversion to annuities per se suppressing demand for the product. Rather, the analysis finds no evidence that respondents are willing to pay more for death benefits or liquidity options beyond what they are willing to pay for a standard immediate annuity.

Figure 4 shows regression coefficients for how much more annual income individuals require to pay a $100,000 premium for an annuity with death benefits or a liquidity option, compared to the standard immediate annuity.

Neither of these coefficients is statistically different from zero. In other words, despite the notion that the lack of ability to bequeath an annuity and its illiquidity are major reasons why individuals do not want to annuitize, the RCT finds that products relaxing these constraints would be no more attractive to consumers than the standard annuity (which many actually like as is).

Conclusion

Annuity demand has persistently fallen far short of what economic theory predicts, a discrepancy known as the “annuity puzzle.” This brief reports on findings from a recent study of demand for annuities based on a survey of older individuals with over $100,000 in investable assets. The study elicited respondents’ willingness to buy an annuity, and used an RCT to test whether consumers would find annuities with death benefits or greater liquidity more attractive.

The study found that roughly half of respondents would be willing to buy an annuity at prevailing market rates, a far greater share than those who actually do buy annuities. The fact that so many respondents wanted annuities at these prices suggests that explanations relying on reasons why consumers might not want to annuitize at market prices cannot capture the whole story. Respondents also did not appear more willing to buy annuities that address their most prominent aversive qualities – that they cannot be bequeathed and that they are illiquid.

Overall, the findings suggest that a lack of desire to buy annuities is not the reason why roughly 40 percent of individuals with over $100,000 in financial assets do not annuitize (the 50 percent who want to annuitize minus the 12 percent who do so). Rather, the findings are consistent with channel factors, like lack of familiarity with annuities or how exactly to go about buying them, being major impediments to annuitization.

References

Arapakis, Karolos and Gal Wettstein. 2023a. “Longevity Risk: An Essay.” Special Report. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Arapakis, Karolos and Gal Wettstein. 2023b. “What Matters for Annuity Demand: Objective Life Expectancy or Subjective Survival Pessimism?” Working Paper 2023-2. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Bernheim, B. Douglas. 1991. “The Vanishing Nest Egg: Reflections on Saving in America.” Berkeley, CA: Priority Press Publications.

Gollwitzer, Peter M. 1999. “Implementation Intentions: Strong Effects of Simple Plans.” The American Psychologist 54(7): 493-503.

Hosseini, Roozbeh. 2015. “Adverse Selection in the Annuity Market and the Role for Social Security.” Journal of Political Economy 123(4): 941-984.

Hubbard, Robert and Kenneth Judd. 1987. “Social Security and Individual Welfare: Precautionary Saving, Borrowing Constraints, and the Payroll Tax.” American Economic Review 77(3): 630-646.

Laitner, John, Dan Silverman and Dmitriy Stolyarov. 2018. “The Role of Annuitized Wealth in Post-retirement Behavior.” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 10(3): 71-117.

Leventhal, Howard, Robert Singer and Susan Jones. 1965. “Effects of Fear and Specificity of Recommendation Upon Attitudes and Behavior.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

Lusardi, Annamaria and Olivia S. Mitchell. 2014. “The Economic Importance of Financial Literacy: Theory and Evidence.” Journal of Economic Literature 52(1): 5-44.

Mitchell, Olivia S., James M. Poterba, Mark J. Warshawsky, and Jeffrey R. Brown. 1999. “New Evidence on the Money’s Worth of Individual Annuities.” The American Economic Review 89(5): 1299-1318.

O’Dea, Cormac and David Sturrock. 2023. “Survival Pessimism and the Demand for Annuities.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 105(2): 442-457.

Pashchenko, Svetlana. 2013. “Accounting for Non-Annuitization.” Journal of Public Economics 98(C): 53-67.

Wettstein, Gal, Alicia H. Munnell, Wenliang Hou, and Nilufer Gok. 2021. “The Value of Annuities.” Working Paper 2021-5. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Yaari, Menahem E. 1965. “Uncertain Lifetime, Life Insurance, and the Theory of the Consumer.” The Review of Economic Studies 32(2): 137-150.

Endnotes

- 1Arapakis and Wettstein (2023a).

- 2Yaari (1965).

- 3Although wealth is endogenous (i.e., buying an annuity reduces wealth), individuals with less than $100,000 of financial assets annuitize less, with approximately 7 percent of the under $100,000 population receiving annuity income.

- 4Mitchell et al. (1999) and Wettstein et al. (2021).

- 5See Hubbard and Judd (1987) and Laitner, Silverman, and Stolyarov (2018).

- 6Arapakis and Wettstein (2023a).

- 7Bernheim (1991); Pashchenko (2013); and Hosseini (2015).

- 8O’Dea and Sturrock (2023) and Arapakis and Wettstein (2023b).

- 9Lusardi and Mitchell (2014).

- 10Leventhal, Singer, and Jones (1965).

- 11For example, see Gollwitzer (1999).

- 1213.6 percent of respondents already owned an annuity, a share similar to that found in the HRS for a similar population.

- 13In the United States, annuities are generally priced only based on gender, age, and state of residence.