How Will COVID Affect Completed Fertility?

The brief’s key findings are:

- Birth rates have been falling since the Great Recession, and many thought COVID might accelerate this decline.

- Indeed, birth rates did drop substantially early in the pandemic, but by the end of 2021, the COVID effect was actually positive.

- This uptick may well be temporary, though, as early data show that the ideal number of kids has:

- dropped sharply for women in their 20s; and

- held steady for women in their early 30s.

- And evidence from the Great Recession suggests that the expectations of these women will not rise as they age.

- If the drop in expectations holds in more comprehensive surveys, birth rates are likely to keep falling, and at a faster pace than before COVID.

Introduction

Birth rates in the United States have been declining since the Great Recession, and many thought that COVID-19 might accelerate this decline. And, indeed, birth rates early in the pandemic did drop substantially. However, when the economy swiftly recovered from COVID, birth rates in 2021 ticked up for the first time since 2014. The question is what happens next: is this uptick simply a temporary blip or a sign that the decade-long decline in fertility rates is over?

To assess how COVID might affect completed fertility, this brief, based on a recent paper, uses a two-pronged approach.1Chen, Gok, and Munnell (2023). First, it examines the change in birth rates by age in 2020 and 2021 using data from the National Vital Statistics System to quantify the recent COVID-era changes in birth rates. Second, to shed light on fertility trends going forward, the analysis turns from recent birth patterns, which represent a snapshot for any given year, to expectations data, which suggest how many children women anticipate having overall.

The discussion proceeds as follows. The first section provides some background on fertility trends and expectations. The second section describes the data and methodology. The third section presents results for the two separate approaches. The first shows that the pandemic resulted in a large initial decline in fertility in late 2020, but by the end of 2021, COVID’s independent impact on fertility was actually positive.

The second finds that, according to early data on fertility expectations, the ideal number of kids has dropped sharply for women in their 20s and held steady for women in their 30s; and evidence from the Great Recession suggests that fertility will not rise as they age. If the drop in expectations holds in more comprehensive surveys, birth rates are likely to keep falling, and at a faster pace than before COVID.

The final section concludes that a lower fertility rate will likely result in a smaller workforce, slower economic growth, and higher required tax rates for pay-as-you-go programs such as Social Security, but it also reflects the evolving preferences of women today.

Background

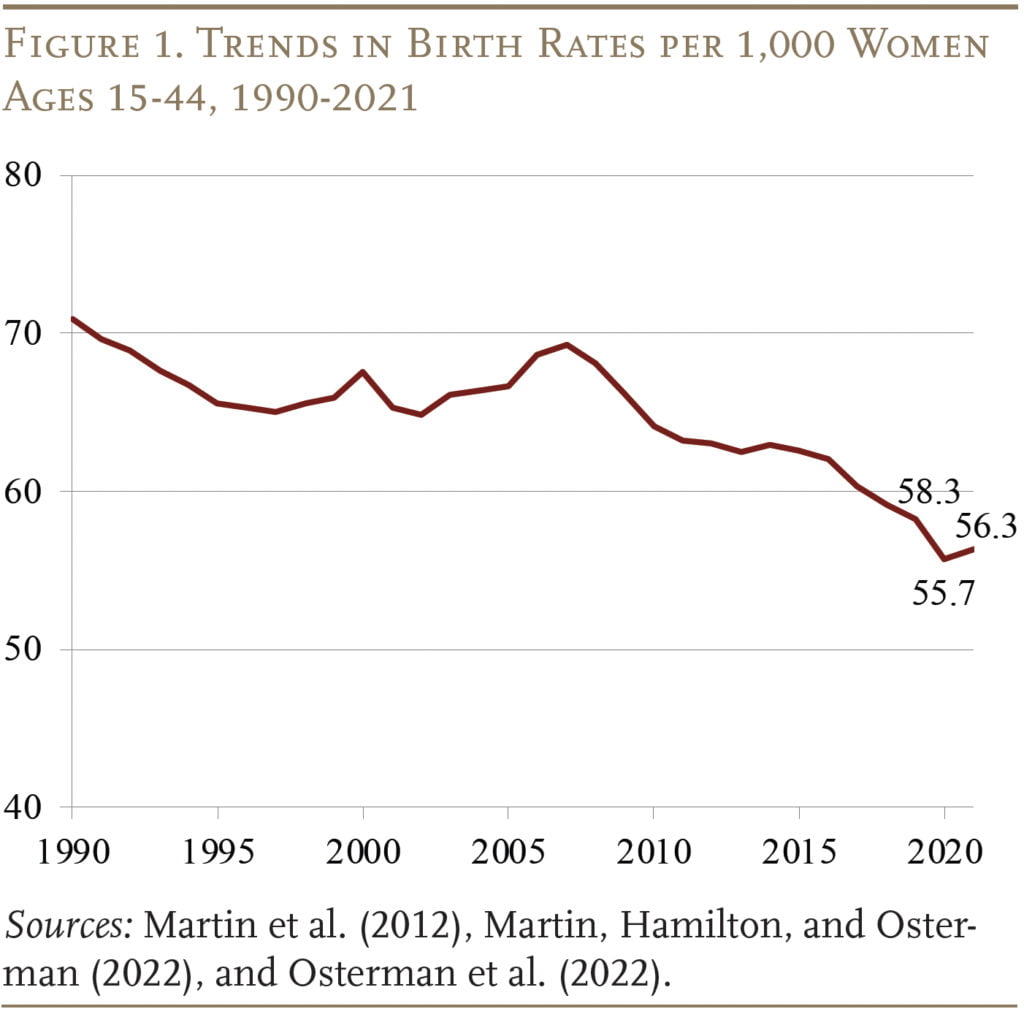

Fertility rates generally fall during a recession or crisis.2The relationship between the economy and fertility is well documented: fertility rates generally decrease during recessions and increase in recoveries. This finding is true both in aggregate (Lee and Miller 1990; Schaller 2016; and Munnell, Chen, and Sanzenbacher 2019) and at the individual level (Lindo 2010; Dettling and Kearny 2014; Kearny and Wilson 2018; and Autor, Dorn and Hanson 2019). Similarly, conceptions decline when mortality rates are high (Herteliu, Richmond, and Roehner 2018; Richmond and Roehner 2018). In the United States, traumatic events such as the Cuban Missile Crisis, Oklahoma City Bombing, and 9/11 had negative impacts on fertility (Raschky and Wang 2012; Rodgers, St. John, and Coleman 2005; and Ruther 2010). In 2020, COVID shut down businesses, drove unemployment to a staggering 14.7 percent, and resulted in over 350,000 deaths.3National Center for Health Statistics (2021). And, initially, the fertility rate did drop, falling from 58.3 births per 1,000 women in 2019 to 55.7 births per 1,000 women in 2020 (see Figure 1). The COVID impact in 2020 would largely be expected to occur at the very end of the year, as any drop-off in conceptions for women within the United States at the onset of the pandemic in March would not show up until December.4One other COVID impact on birth rates would show up earlier. Lockdowns globally and travel restrictions meant that many foreign-born mothers could not travel or return to the United States, resulting in a decline in births beginning earlier in 2020 (Bailey, Currie, and Schwandt 2022).

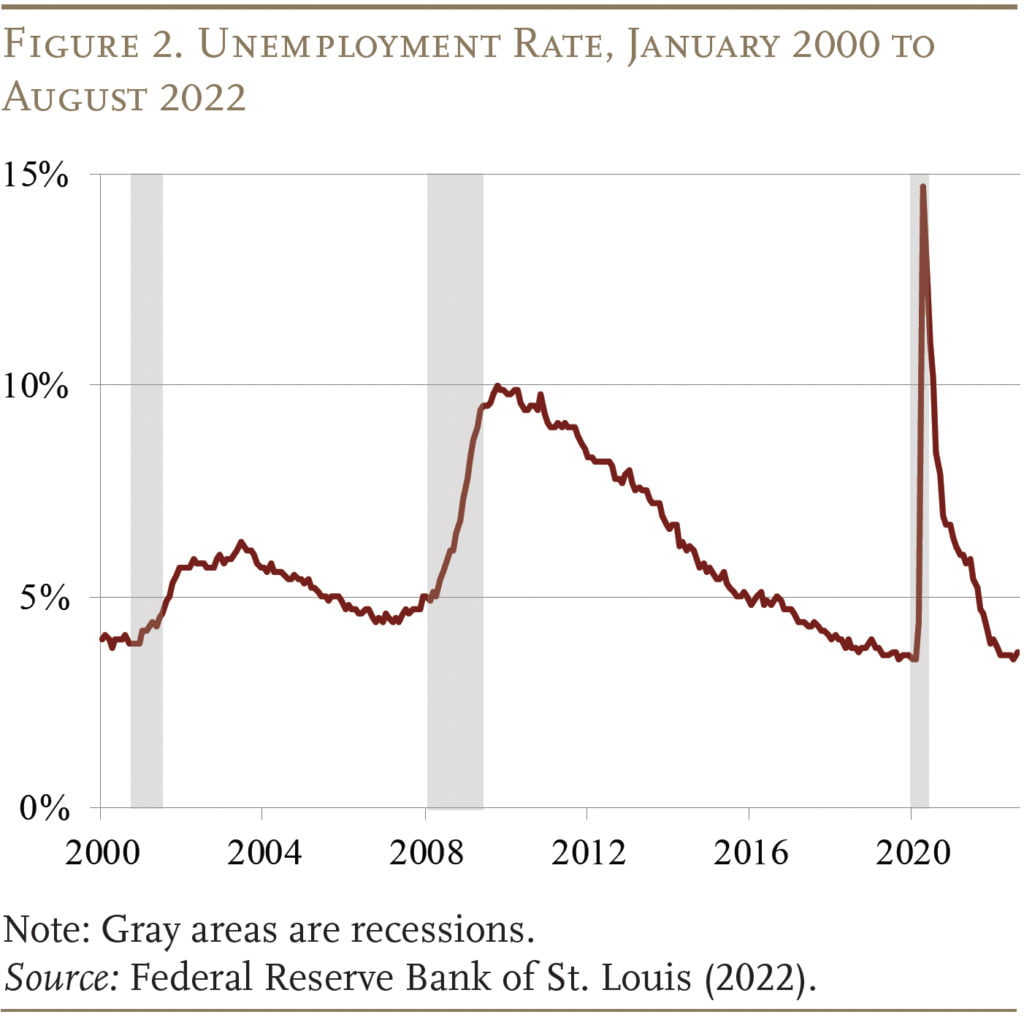

Interestingly, though, birth rates turned upward in 2021 for the first time since 2014. Three factors contributed to the uptick. First, although unemployment rose sharply, it also declined rapidly (see Figure 2), and researchers have shown that declining unemployment leads to higher births.5Kearney and Levine (2022). Second, Congress provided substantial financial support to households, mediating the impact of income losses, which, as prior literature suggests, should also improve birth rates.6A few papers show that exogenous changes in earnings lead to increases in fertility. Black et al. (2013) examined fertility in coal-producing areas after coal price increases; Kearney and Wilson (2018) studied fertility after local fracking booms; and Dettling and Kearney (2014) and Lovenheim and Mumford (2013) explored fertility after housing booms; all found these increases in income led to higher fertility. Finally, as restrictions began to lift, and vaccine rollouts began, the fear and uncertainty related to the pandemic may have also worn off and contributed to the rebound in birth rates.

The question is whether the recent rise in birth rates represents a permanent increase in the total number of children women will end up having or simply reflects a shift in the timing of births. Two factors can shed some light on this question: 1) the ages at which the rises in birth rates occurred; and 2) any changes in fertility expectations. The age distribution of the rise in fertility matters because childbearing has an obvious biological limit.7The higher the age of the woman, the longer it takes to get pregnant, the higher the risk of miscarriage, and hence the fewer resulting live births (Morgan and Rackin 2010; Schmidt et al. 2012; and Alves de Carvalho, Wong, and Mirando-Ribeiro 2016). As a result, increases in fertility among women in their late 30s or 40+ largely reflect permanent increases, but they account for only a small portion of total births. In contrast, higher fertility among women in their 20s and early 30s, which matters a lot, can represent either permanent increases or shifts in the timing of births. To help distinguish between these two possible explanations for this younger group, analysts rely on fertility expectations.

Data and Methods

The analysis is based on birth data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Vital Statistics System (NVSS) and data on local economic conditions from Census’ Current Population Survey (CPS). Data on fertility expectations come from the National Opinion Research Center’s General Social Survey (GSS)8The GSS is a nationally representative survey of adults in the United States conducted since 1972 by the National Opinion Research Center (NORC) at the University of Chicago. The GSS collects data on contemporary American society in order to monitor and explain trends in opinions, attitudes, and behaviors. The GSS is the single best source for a broad range of sociological and attitudinal data, although other surveys have higher quality data for specific questions, such as birth expectations. and the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 79 Young Adult (NLSY79YA).

The first step is to estimate how much of the change in fertility during the pandemic is a direct result of the pandemic, as opposed to general birth trends, and to isolate the change by age group. This step involves a regression to compare births of children conceived pre- and post-March 2020, by age and educational group, to births of children conceived before and after the same months in 2016-2019.

To better understand whether these fluctuations are temporary or more permanent, the second step turns to expectations, which prior studies have found to be an important predictor of how many children women will end up having, particularly for women after age 30.9Empirical research has consistently found that fertility expectations, particularly expectations after age 30, are a strong predictor of the number of children women will end up having. See Barber (2001); Bongaarts (1992); Schoen et al. (1999); Westoff and Ryder (1977); Hayford (2009); and Chen and Gok (2021). The analysis, which is based on questions on the ideal number of children from the GSS, examines whether the total number of children desired among women in their 20s and early 30s changed after the onset of COVID.10The more widely used surveys on expectations – the National Survey of Family Growth and the NLSY – will not have data on fertility expectations after COVID until 2023 or later. As part of the expectations analysis, we also compare the most recent expectations data by age group to expectations during and after the Great Recession. Data on expectations come from the NLSY79YA group, many of whom were in their 20s and early 30s during the Great Recession. If women who were in their childbearing years during the Great Recession adjusted their fertility expectations downward and are now having fewer children, then declines in fertility expectations among women today may also result in lower completed fertility.

Results

The first set of results shows how the pandemic affected fertility trends. The second set turns to the expectations data – both from the pandemic period and from the experience of the Great Recession – to assess whether changes in fertility today might impact completed fertility.

Changes in Birth Rates During COVID

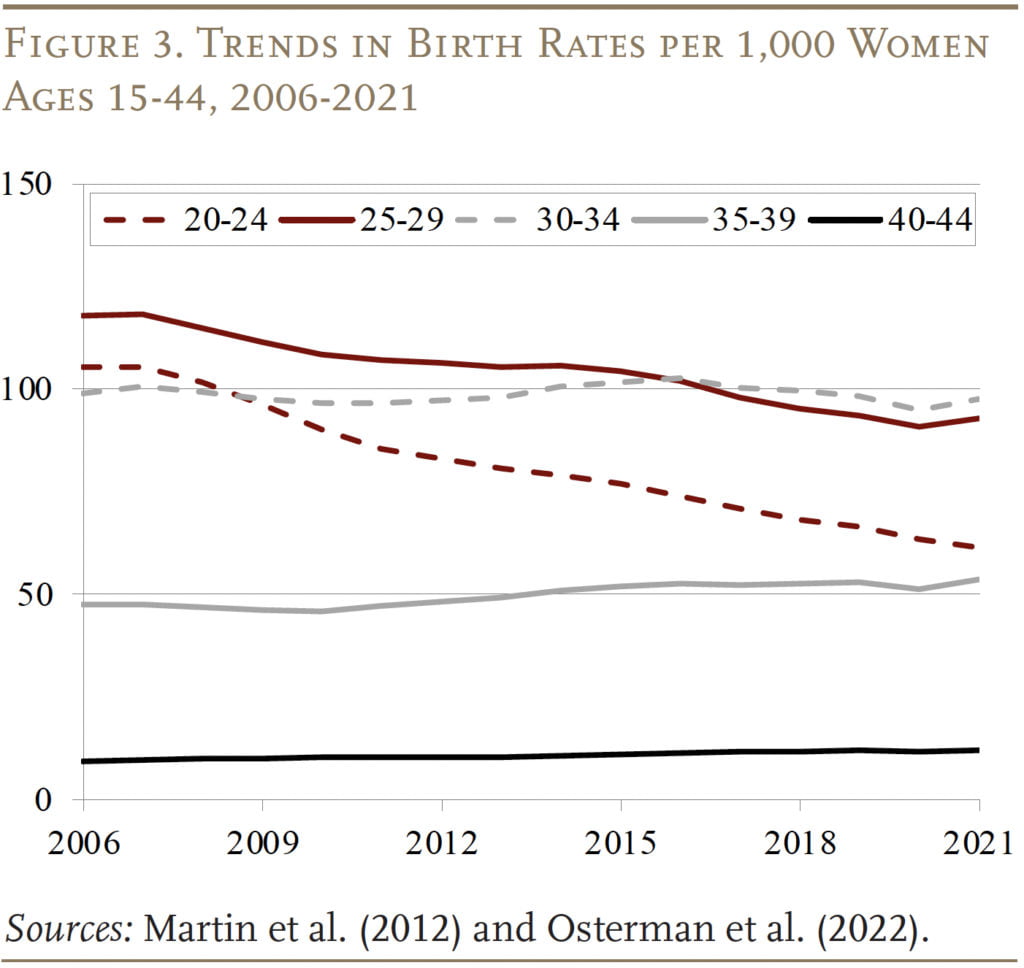

To set the stage for how the pandemic impacted fertility, it is important to first understand pre-pandemic trends in fertility (see Figure 3). From 2006-2019, births among women ages 20-24 and 25-29 declined rapidly. Part of this decline was due to delays in the timing of births, as fertility among women in their 30s and 40s was increasing. However, interestingly, births among women ages 30-34 also declined from 2016-2019.

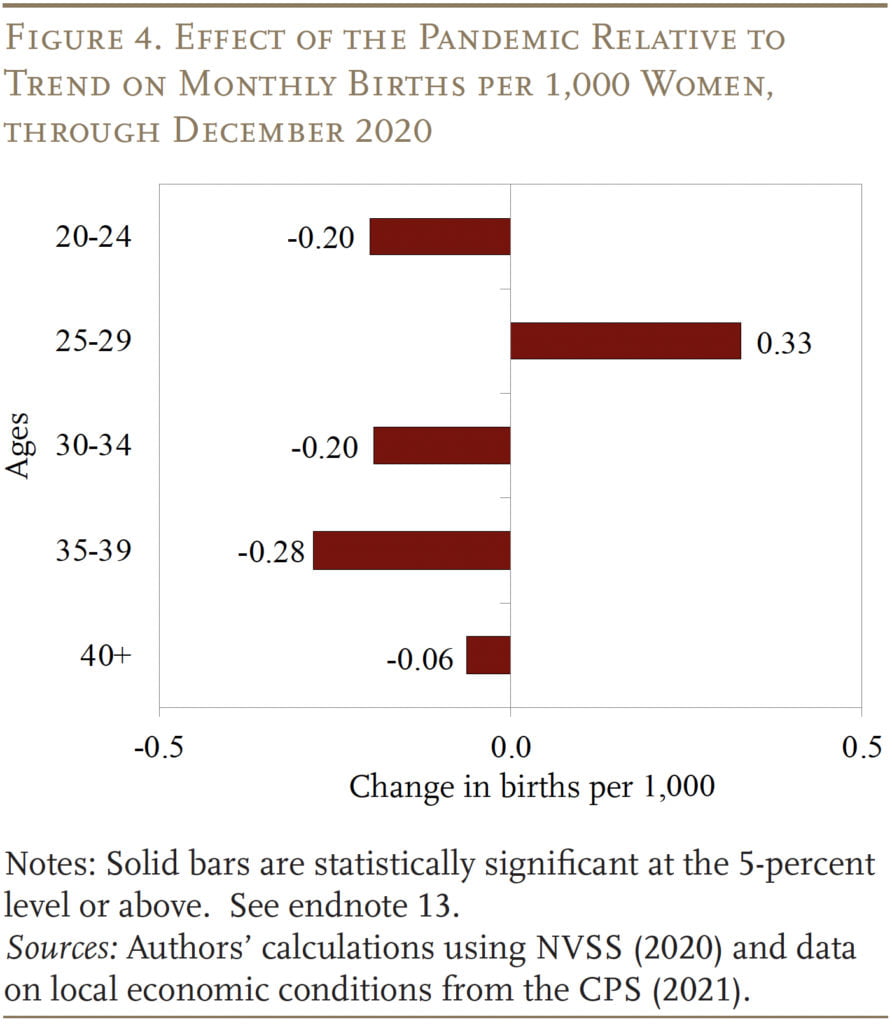

With an understanding of pre-existing birth trends, we can now evaluate the pandemic’s effect on fertility. Figure 4 shows the results of a regression that compares the births of children conceived pre- and post-March 2020 to births of children conceived before and after the same months in 2016-2019 by age and educational groups.11Mechanically, the regression compares births conceived in, for example, March 2020 with the average of births conceived in March 2016-2019, de-trended for annual changes. The bars show that, for most age groups, the initial economic and health shocks in March-April 2020 put downward pressure on births relative to the existing declining birth trends shown in Figure 3.12The existing declining trend in births canceled out the small uptick for women ages 25-29. On net, then, births among women ages 25-29 were flat in 2020.

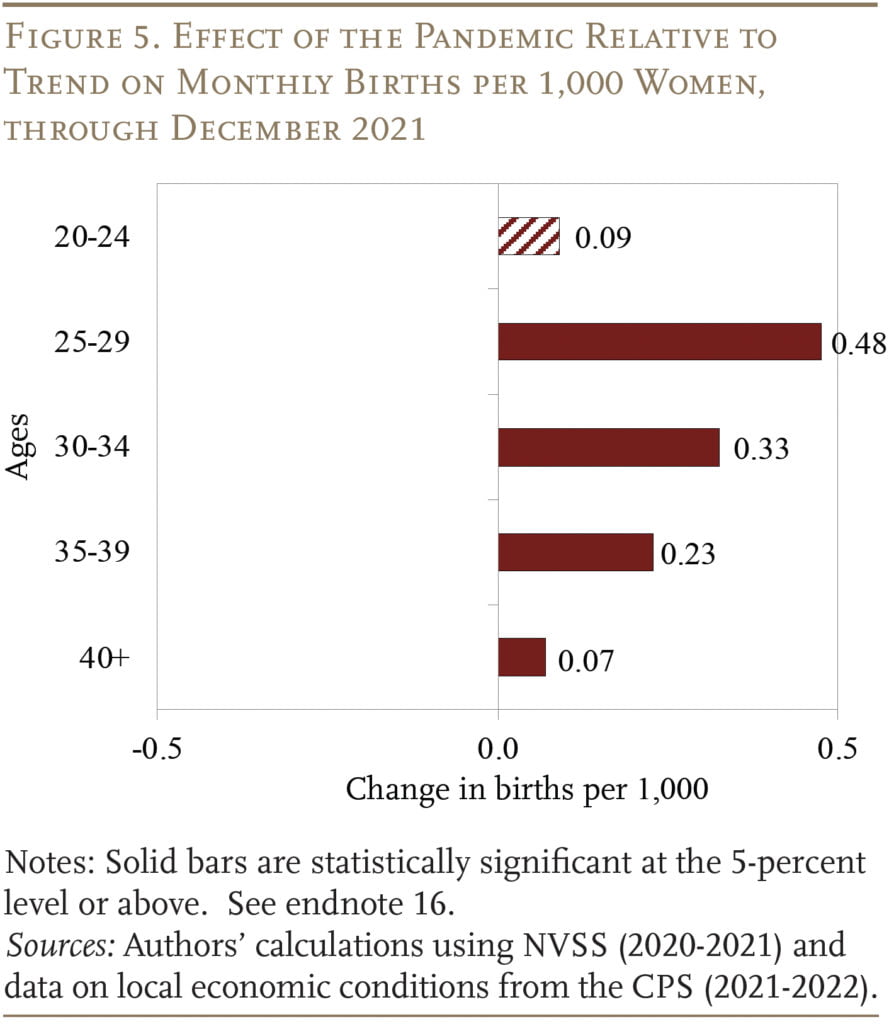

Interestingly, when the picture is extended through the end of 2021, the isolated effect of COVID increased births relative to the trend. This turnaround is captured in the regression results presented in Figure 5, which reflect the same analysis as Figure 413The regression also controls for year trends, average COVID deaths, and unemployment rate by state and by education group as well as month, state, and educational group fixed-effects., except now with births from 2021 included.14The fixed-effect regression is the same as the one represented in Figure 4, except it does not include state fixed-effects, unemployment rates by state, and deaths per 1,000 by state because, at time of writing, birth data by state has not been released for 2021. These results show that the net impact of COVID on fertility during the entire 2020-2021 period was positive, so births were higher than what the trend from prior years would predict.15Actual birth rates among women ages 35-39 and 40+ are increasing over the period 2016-2021, with March 2020-December 2021 defined as the pandemic period. The equation presents birth rate estimates, all else equal. Since unemployment rates are declining over this period, the estimates for the trend in this age group become positive. The general trend by age group is shown in Figure 3.

For women 40+, and to some extent women ages 35-39, the higher-than-trend birth rates during the pandemic likely reflect permanent increases rather than shifting childbirth earlier.16The regression also controls for average COVID deaths and unemployment rate as well as month and educational group fixed-effects. These increases, however, may have limited impact on aggregate completed fertility, since births to women 35+ account for only 20 percent of total births. The more relevant groups are women in their 20s and early 30s, who account for the bulk of births. For these groups, fertility expectations – which as noted are a strong predictor of completed fertility (particularly for those in their early 30s) – may provide some insight as to whether the uptick is temporary or permanent.

Changes in Fertility Expectations During COVID and the Great Recession

The analysis begins by looking at currently available data on expectations for the past two years to assess the COVID period and then explores whether expectations patterns during a previous crisis – the Great Recession – were only temporary or persisted.

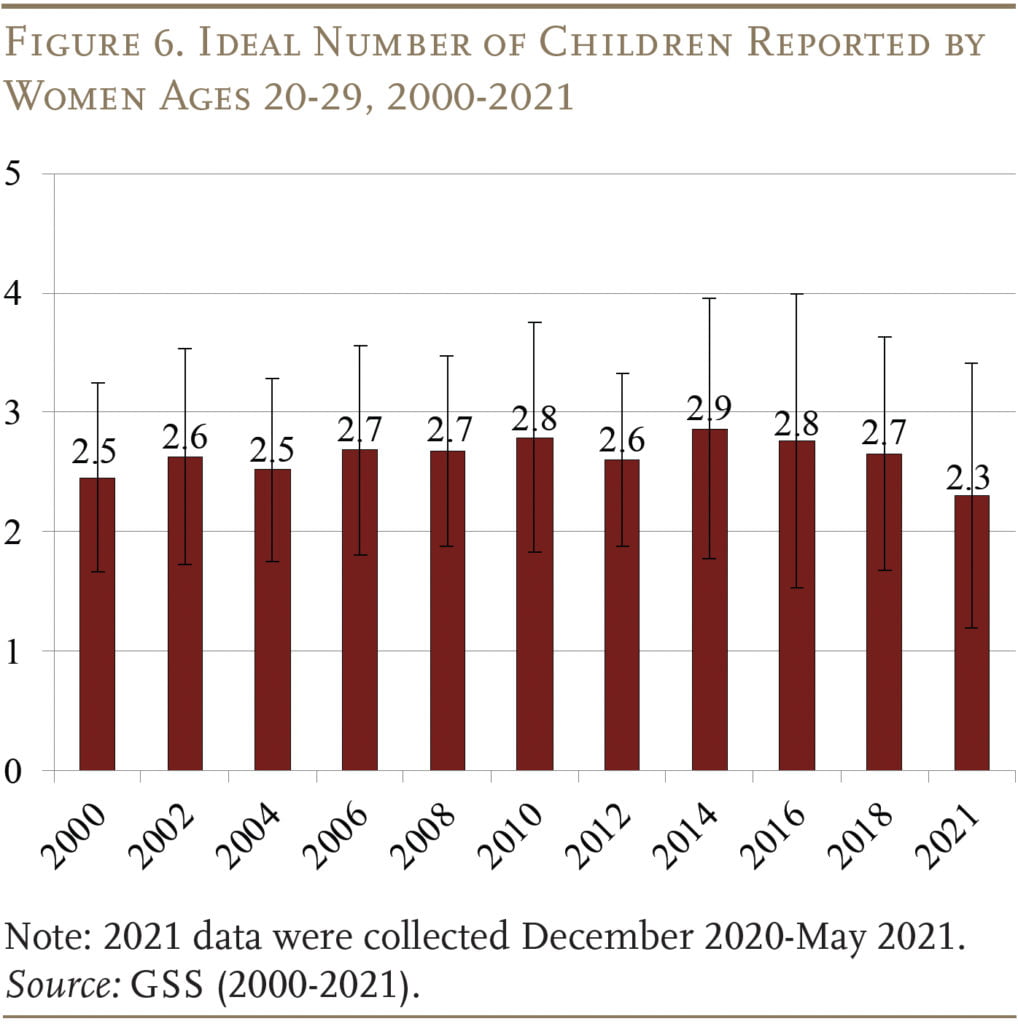

Expectations Data from COVID. The GSS data provide an early indicator of how COVID might have affected the fertility expectations of women, though the sample size is small. According to the GSS, the number of children that women in their 20s viewed as ideal plummeted in 2021 (see Figure 6). So, despite the small uptick in births among 25-29 year olds during the pandemic, women in their 20s now want fewer children than they did pre-pandemic. If these early indicators are confirmed in surveys with larger samples, such as the National Survey of Family Growth, they would suggest a decline in completed births among women in their 20s today.

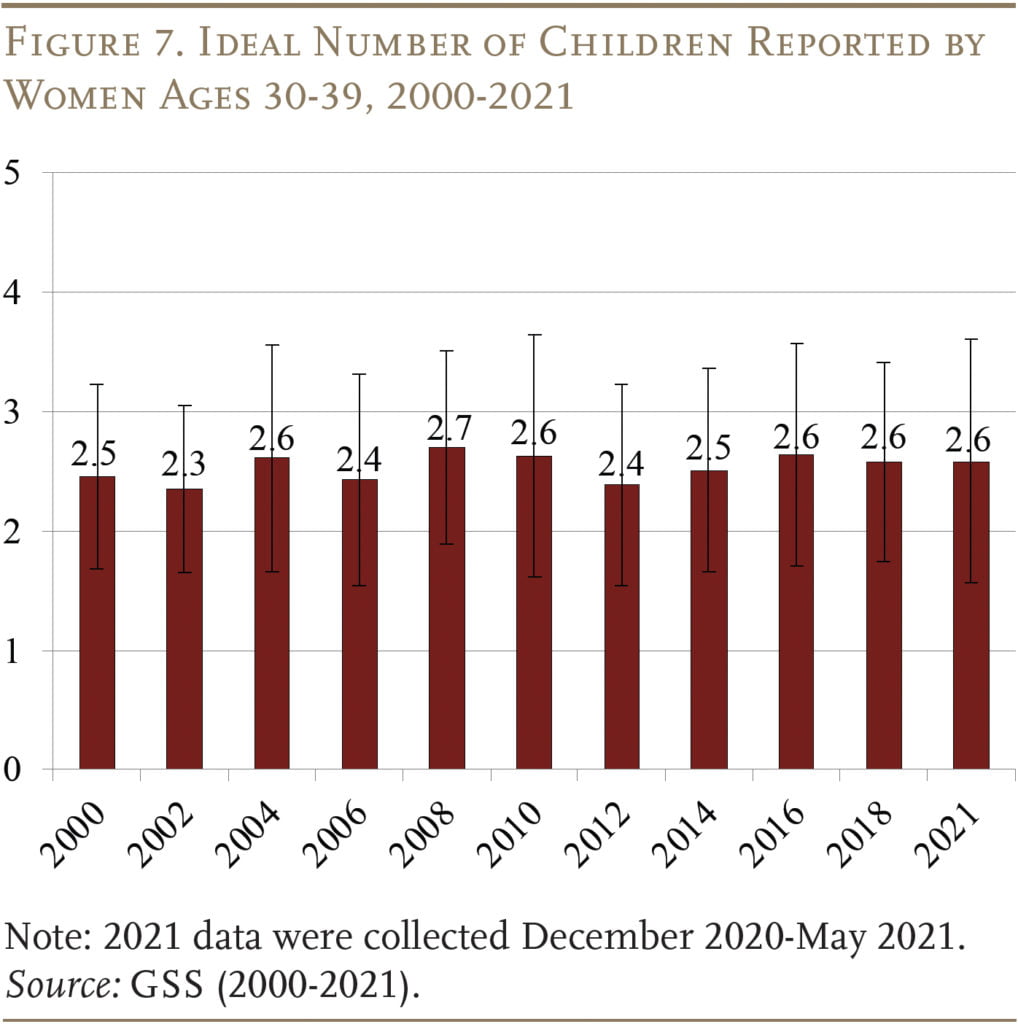

In contrast, the fertility expectations of women in their 30s did not change (see Figure 7), suggesting that the pandemic decline and later increase reflects shifts in timing for this group rather than a change in the total number of children they will have. For women in their 30s, as noted, our main interest is the early 30s. With the GSS data, though, it is not feasible to break out the early and late 30s separately, so we assume that the stability for the whole group also reflects those in their early 30s.

Expectations Data from the Great Recession. The dramatic decline in the number of children viewed as ideal among women in their 20s may merely reflect the initial reaction to the shock of the pandemic. To examine if declines in fertility expectations after an economic shock persist, the analysis turns to the Great Recession for insights.

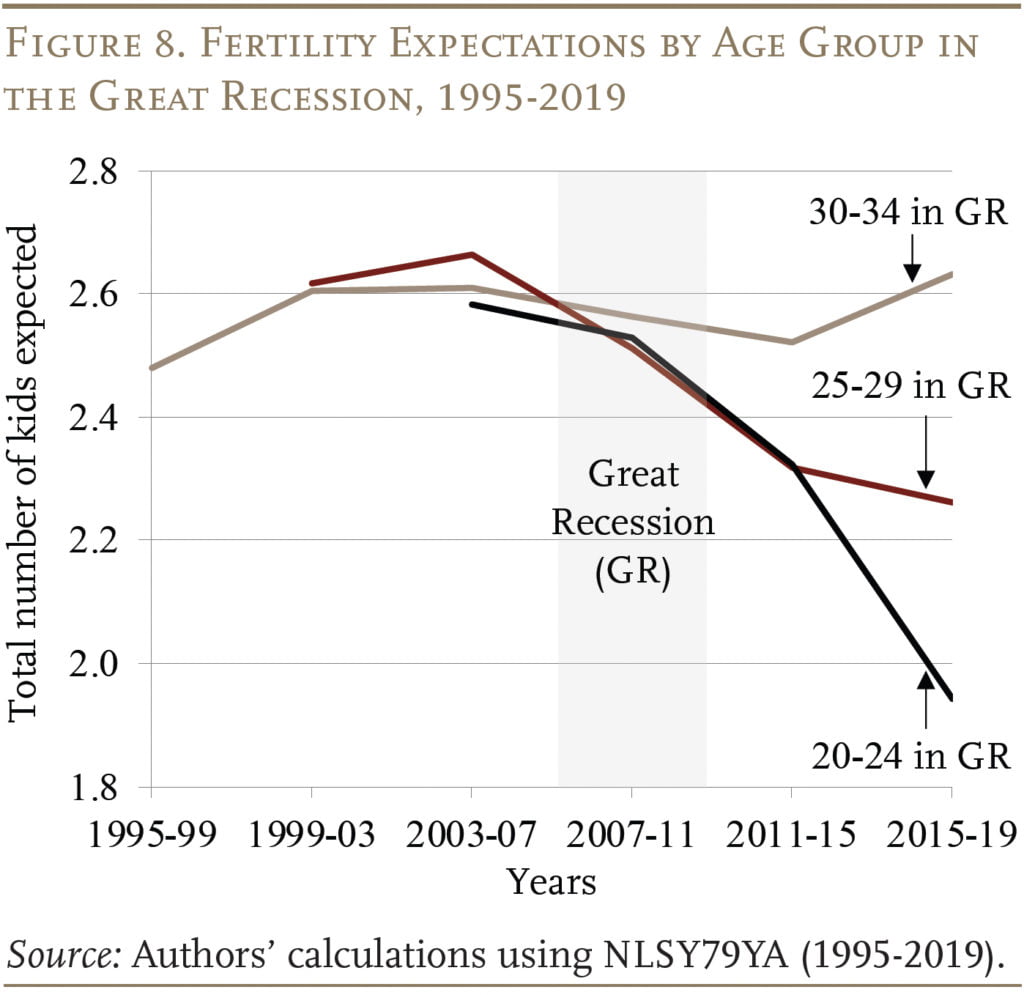

Figure 8 shows that fertility expectations among women who were ages 20-24 and 25-29 during the Great Recession initially plummeted, just as we observe after COVID. Fertility expectations then continued to decrease as these age groups entered their 30s over the past decade. This pattern suggests that the drop in expectations among today’s 20-24 and 25-29 year olds may continue in future years.17These trends can also be seen in birth trends in Figure 3.

Mirroring the early indicators of women in their 30s today, fertility expectations among women 30-34 during the Great Recession also remained stable during that time. The stability of this group’s expectations has persisted in the years since the Great Recession, providing support for the hypothesis that women currently in their 30s are not likely to increase the total number of children they have.

The overall takeaway from the expectations data is that fertility will continue to decline, driven by women currently 20-24 and 25-29. And despite increases in recent birth rates, completed fertility among women 30-34 is unlikely to increase.

Conclusion

When COVID brought on a health crisis and shut down many parts of the economy in 2020, many expected the fertility rate to drop even more than it has in recent years. While initially the severity of the crisis did result in a large drop in fertility, the swift labor market recovery and income support for families led to an uptick in 2021.

Expectations data offer two pieces of evidence to suggest that this uptick only reflects a shift in the timing of births, not a change in the total number of children overall. First, early data on fertility expectations fell among women ages 20-29 in 2021 and did not change for women ages 30-34, so the increases in births in 2021 likely do not reflect a reversal of trends and increased birth rates going forward. Second, an analysis of the decline in fertility expectations for women 20-24 and 25-29 during the Great Recession finds that this decline persisted over the next 10 years – as these women entered their 30s – despite improving economic conditions. Similar to today, the fertility expectations of women 30-34 during the Great Recession remained stable during that economic crisis; and that stability persisted years after the Great Recession. Taken together, the current data suggest that completed fertility is likely to continue to decline, driven primarily by women 20-29 today.

A decline in fertility will likely result in a smaller workforce, slower economic growth, and higher required tax rates for pay-as-you-go programs such as Social Security, but it also reflects shifts in the preferences of women today as we have seen earlier in other developed nations.

References

De Carvalho, Angelita Alves, Laura L. R. Wong, and Paula Miranda-Ribeiro. 2016. “Discrepant Fertility in Brazil: An Analysis of Women Who Have Fewer Children Than Desired (1996 and 2006).” Revista Latinoamericana de Población 10(18): 83-106.

Autor, David, David Dorn, and Gordon Hanson. 2019. “When Work Disappears: Manufacturing Decline and the Falling Marriage Market Value of Young Men.” American Economic Review 1(2): 161-178.

Bailey, Martha J., Janet Currie, and Hannes Schwandt. 2022. “The Covid-19 Baby Bump: The Unexpected Increase in US Fertility Rates in Response to the Pandemic.” Working Paper w30569. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Barber, Jennifer S. 2001. “Ideational Influences on the Transition to Parenthood: Attitudes Toward Childbearing and Competing Alternatives.” Social Psychology Quarterly 64(2): 101-127.

Black, Dan A., Natalia Kolesnikova, Seth G. Sanders, and Lowell J. Taylor. 2013. “Are Children ‘Normal’?” The Review of Economics and Statistics 95(1): 21-33.

Bongaarts, John. 1992. “Do Reproductive Intentions Matter?” International Family Planning Perspectives 18(3): 102-108.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Vital Statistics System, 2020-2021. Atlanta, GA.

Chen, Anqi and Nilufer Gok. 2021. “Will Women Catch Up to Their Fertility Expectations?” Working Paper 2021-4. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Chen, Anqi, Nilufer Gok, and Alicia H. Munnell. 2023. “How Will COVID Affect the Completed Fertility Rate?” Working Paper 2023-1. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Dettling, Lisa J. and Melissa S. Kearney. 2014. “House Prices and Birth Rates: The Impact of the Real Estate Market on the Decision to Have a Baby.” Journal of Public Economics 110: 82-100.

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Federal Reserve Economic Data, 2022. St. Louis, MO.

Hayford, Sarah R. 2009. “The Evolution of Fertility Expectations Over the Life Course.” Demography 46(4): 765-783.

Herteliu, Claudiu, Peter Richmond, and Bertrand M. Roehner. 2018. “Deciphering the Fluctuations of High Frequency Birth Rates.” Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 509: 1046-1061.

Kearney, Melissa S. and Phillip B. Levine. 2022. “The Causes and Consequences of Declining U.S. Fertility.” Washington, DC: Aspen Institute.

Kearney, Melissa S. and Riley Wilson. 2018. “Male Earnings, Marriageable Men, and Nonmarital Fertility: Evidence from the Fracking Boom.” Review of Economics and Statistics 100(4): 678-690.

Lee, Ronald D. and Timothy Miller. 1990. “Population Growth, Externalities to Childbearing, and Fertility Policy in Developing Countries.” The World Bank Economic Review 4(1): 275-304.

Lindo, Jason M. 2010. “Are Children Really Inferior Goods? Evidence from Displacement-driven Income Shocks.” Journal of Human Resources 45(2): 301-327.

Lovenheim, Michael F. and Kevin J. Mumford. 2013. “Do Family Wealth Shocks Affect Fertility Choices? Evidence from the Housing Market?” The Review of Economics and Statistics 95(2): 464-475.

Martin, Joyce A., Brady E. Hamilton, and Michelle J. K. Osterman. 2022. “Births in the United States, 2021.” NCHS Data Brief No. 442. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

Martin, Joyce A., Brady E. Hamilton, Stephanie J. Ventura, Michelle J. K. Osterman, Elizabeth C. Wilson, and T. J. Mathews. 2012. “Births: Final Data for 2010.” National Vital Statistics Reports 61(1). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

Morgan, S. Philip and Heather Rackin. 2010. “The Correspondence between Fertility Intentions and Behavior in the United States.” Population and Development Review 36(1): 91-118.

Munnell, Alicia H., Anqi Chen, and Geoffrey T. Sanzenbacher. 2019. “Is the Drop in Fertility Due to the Great Recession or a Permanent Change?” Working Paper 2019-7. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

National Center for Health Statistics. 2021. “NVSS Vital Statistics Rapid Release: Quarterly Provisional Estimates for General Fertility Rates.” Washington, DC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/natality-dashboard.htm

National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago. General Social Survey, 2000-2021. Chicago, IL.

Osterman, Michelle J. K., Brady E. Hamilton, Joyce A. Martin, Anne K. Driscoll, and Claudia P. Valenzuela. 2022. “Births: Final Data for 2020.” National Vital Statistics Reports 70(17). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

Raschky, Paul and Liang Choon Wang. 2012. “Reproductive Behaviour at the End of the World: The Effect of the Cuban Missile Crisis on U.S. Fertility.” Working Paper 54-12. Clayton, Australia: Monash University, Department of Economics.

Richmond, Peter and Bertrand M. Roehner. 2018. “Coupling Between Death Spikes and Birth Troughs. Part 1: Evidence.” Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 506: 97-111.

Rodgers, Joseph Lee, Craig A. St. John, and Ronnie Coleman. 2005. “Did Fertility Go Up After the Oklahoma City Bombing? An Analysis of Births in Metropolitan Counties in Oklahoma, 1990-1999.” Demography 42(4): 675-692.

Ruther, Matt. 2010. “The Fertility Response to September 11th: Evidence from the Five Boroughs.” Poster. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania, Population Studies Center.

Schaller, Jessamyn. 2016. “Booms, Busts, and Fertility Testing the Becker Model Using Gender-Specific Labor Demand.” Journal of Human Resources 51(1): 1-29.

Schmidt, L., T. Sobotka, J. G. Bentzen, and A. Nyboe Andersen. 2012. “Demographic and Medical Consequences of the Postponement of Parenthood.” Human Reproduction Update 18(1): 29-43.

Schoen, Robert, Nan Marie Astone, Young J. Kim, Constance A. Nathanson, and Jason M. Fields. 1999. “Do Fertility Intentions Affect Fertility Behavior?” Journal of Marriage and the Family 61(3): 790-799.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 79 Young Adult, 1995-2019. Washington, DC.

U.S. Census Bureau. Current Population Survey, 2021-2022. Washington, DC.

Westoff, Charles F. and Norman B. Ryder. 1977. “The Predictive Validity of Reproductive Intentions.” Demography 14(4): 431-453.

Endnotes

- 1Chen, Gok, and Munnell (2023).

- 2The relationship between the economy and fertility is well documented: fertility rates generally decrease during recessions and increase in recoveries. This finding is true both in aggregate (Lee and Miller 1990; Schaller 2016; and Munnell, Chen, and Sanzenbacher 2019) and at the individual level (Lindo 2010; Dettling and Kearny 2014; Kearny and Wilson 2018; and Autor, Dorn and Hanson 2019). Similarly, conceptions decline when mortality rates are high (Herteliu, Richmond, and Roehner 2018; Richmond and Roehner 2018). In the United States, traumatic events such as the Cuban Missile Crisis, Oklahoma City Bombing, and 9/11 had negative impacts on fertility (Raschky and Wang 2012; Rodgers, St. John, and Coleman 2005; and Ruther 2010).

- 3National Center for Health Statistics (2021).

- 4One other COVID impact on birth rates would show up earlier. Lockdowns globally and travel restrictions meant that many foreign-born mothers could not travel or return to the United States, resulting in a decline in births beginning earlier in 2020 (Bailey, Currie, and Schwandt 2022).

- 5Kearney and Levine (2022).

- 6A few papers show that exogenous changes in earnings lead to increases in fertility. Black et al. (2013) examined fertility in coal-producing areas after coal price increases; Kearney and Wilson (2018) studied fertility after local fracking booms; and Dettling and Kearney (2014) and Lovenheim and Mumford (2013) explored fertility after housing booms; all found these increases in income led to higher fertility.

- 7The higher the age of the woman, the longer it takes to get pregnant, the higher the risk of miscarriage, and hence the fewer resulting live births (Morgan and Rackin 2010; Schmidt et al. 2012; and Alves de Carvalho, Wong, and Mirando-Ribeiro 2016).

- 8The GSS is a nationally representative survey of adults in the United States conducted since 1972 by the National Opinion Research Center (NORC) at the University of Chicago. The GSS collects data on contemporary American society in order to monitor and explain trends in opinions, attitudes, and behaviors. The GSS is the single best source for a broad range of sociological and attitudinal data, although other surveys have higher quality data for specific questions, such as birth expectations.

- 9Empirical research has consistently found that fertility expectations, particularly expectations after age 30, are a strong predictor of the number of children women will end up having. See Barber (2001); Bongaarts (1992); Schoen et al. (1999); Westoff and Ryder (1977); Hayford (2009); and Chen and Gok (2021).

- 10The more widely used surveys on expectations – the National Survey of Family Growth and the NLSY – will not have data on fertility expectations after COVID until 2023 or later.

- 11Mechanically, the regression compares births conceived in, for example, March 2020 with the average of births conceived in March 2016-2019, de-trended for annual changes.

- 12The existing declining trend in births canceled out the small uptick for women ages 25-29. On net, then, births among women ages 25-29 were flat in 2020.

- 13The regression also controls for year trends, average COVID deaths, and unemployment rate by state and by education group as well as month, state, and educational group fixed-effects.

- 14The fixed-effect regression is the same as the one represented in Figure 4, except it does not include state fixed-effects, unemployment rates by state, and deaths per 1,000 by state because, at time of writing, birth data by state has not been released for 2021.

- 15Actual birth rates among women ages 35-39 and 40+ are increasing over the period 2016-2021, with March 2020-December 2021 defined as the pandemic period. The equation presents birth rate estimates, all else equal. Since unemployment rates are declining over this period, the estimates for the trend in this age group become positive. The general trend by age group is shown in Figure 3.

- 16The regression also controls for average COVID deaths and unemployment rate as well as month and educational group fixed-effects.

- 17These trends can also be seen in birth trends in Figure 3.