Is Unemployment Worse for Black Workers?

The brief’s key findings are:

- Layoffs hurt all workers, but does the pain vary by race?

- The analysis uses administrative data to see how the long-run earnings of displaced workers fared during three different recessions.

- In the long run, Black and White displaced workers both have earnings roughly 30-40 percent lower than their same-race counterparts who were not laid off.

- Though the impact of layoffs is similar, Black workers start with lower earnings, see slower earnings growth, and are more likely to lose a job in the first place.

Introduction

It is well established that losing a job hurts long-run earnings, but it is unclear whether the impact varies by race. On the one hand, displaced Black workers may be hindered relative to their White counterparts due to discrimination in hiring. On the other hand, displaced Black workers may have higher productivity than laid-off White workers who otherwise appear similar, because employers discriminate in termination decisions. Furthermore, Black workers may be less likely to hold “career ladder” jobs, where compensation includes a premium for experience, so job loss may impact them less for that reason, too.

To determine the relative impact of job loss on Black and White workers, this brief, which is based on a recent study, focuses on the impact of displacement during three recessionary periods: 1990-91, 2000-01, and 2008-09.1 The exercise uses administrative data from the U.S. Social Security Administration (SSA) to compare the earnings trajectories – five years before and 10 years after each recession – of displaced workers relative to the trajectories of similar workers who were not displaced.

The discussion proceeds as follows. The first section reviews what is known about the impact of unemployment for Black and White workers. The second section introduces the data and methodology used for the analysis. The third section presents the results, which show that, by 10 years after the initial job loss, both Black and White displaced workers have earnings roughly 30-40 percent lower than same-race workers who were not displaced. The final section concludes that while Black workers are not disproportionately harmed by job loss in the long run, they begin with lower earnings, their earnings grow more slowly than those of White workers, and they are more likely to lose their job in a recession in the first place.

Background

Black workers have always been much more likely to be unemployed or underemployed than their White counterparts; they are the first to be laid off from struggling firms; and they face longer spells of unemployment.2 Yet, while it is well known that job loss hurts the long-run earnings of displaced workers, recent research does not generally address how the effect might vary by racial group.3

Theoretically, workers who lose their jobs due to macroeconomic or industry shocks may have trouble recouping lost earnings because either their human capital depreciates while they are unemployed or they lose an employer-employee relationship with unusually high productivity.4 This inability to fully recover is particularly pronounced for workers who – due to their occupation – require significant firm-specific knowledge to be productive or hold career-ladder jobs, which disproportionately reward long tenure. In addition, a layoff is often a negative signal of productivity on the job market, carrying a wage penalty.

Black workers may be differentially affected by layoffs in offsetting ways. First, Black workers who are laid off might fare worse than identical White workers due to discrimination in the labor market.5 Since Black job-seekers typically receive fewer callbacks than similarly qualified White people, they can either search longer to achieve the same wage or end the search earlier by accepting a lower wage.6 On the other hand, Black workers, possibly due to discrimination, are typically the first to be laid off from struggling firms and may have higher productivity than otherwise similar laid-off White people, which would enable them to recover lost earnings more quickly when they are rehired. Black workers are also less likely to hold career-ladder jobs, where a layoff is most likely to generate large long-term earnings losses.7

Recognizing that all these forces operate simultaneously, this analysis aims at estimating the net impact on earnings from job loss of White and Black men. The comparison is limited to White and Black workers because the race information is less reliable for other ethnic groups; and it is limited to men because, particularly in the early recession, White women appear much less attached to the labor force than Black women.8

Data and Methodology

The data come from SSA’s Continuous Work History Sample (CWHS), which contains earnings records for a 1-percent sample of the population. The advantage of this dataset is its size and reliability. The disadvantage is that it has very limited demographic information about the workers.9

Identifying Displaced Workers

Like prior studies, this analysis starts by identifying a sample of workers (ages 28-45) in three periods of high unemployment: 1990-91, 2000-01, and 2008-09.10 The focus on job loss during a recession is an attempt to identify workers whose termination was due to macroeconomic shocks, rather than low productivity.11 For each period, the sample is limited to workers with stable pre-recession jobs – that is, workers who were employed with the same employer for five years prior to the recession. The earnings trajectories of those displaced are then compared to a control group who remained employed throughout the recession.

Of course, not all job separations are associated with a loss in earnings; often people who switch jobs see their earnings increase. Identifying “displaced” workers involves finding those who experienced a “substantial drop” in earnings. This calculation compares the separator’s average earnings in the five years before the recession with average earnings during the recession years. Displaced workers are defined as those whose percentage change in earnings falls below the 25th percentile of this distribution.

Sample Characteristics

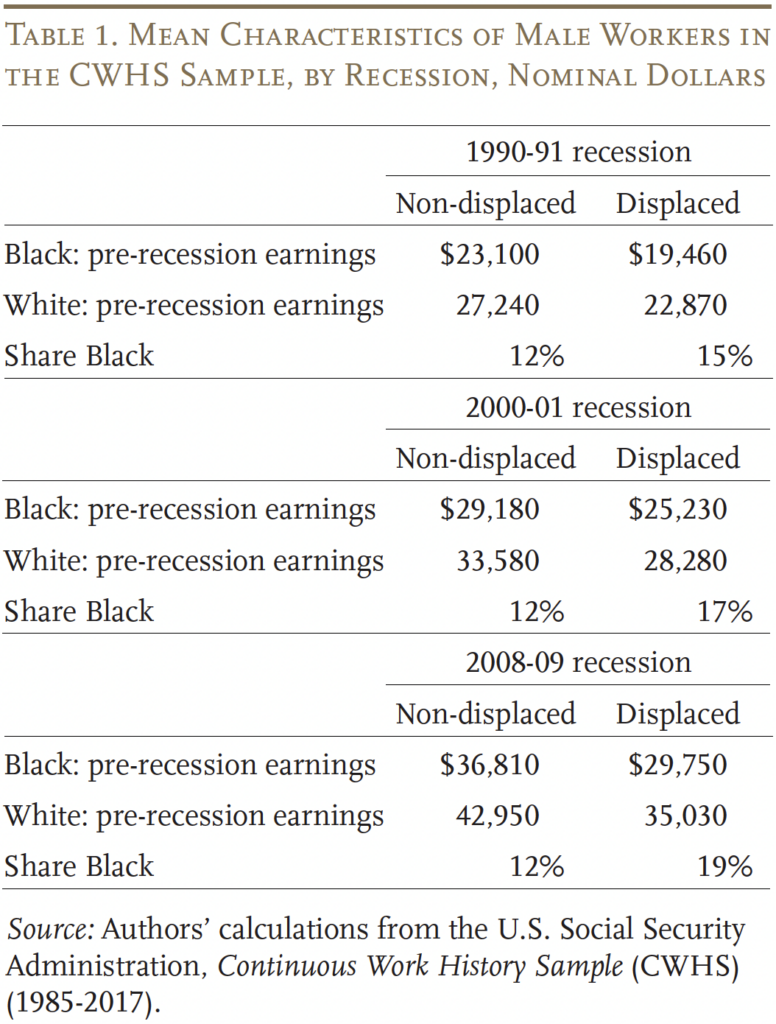

Before describing the regression analysis, it is helpful to consider the characteristics of displaced and non-displaced workers, by race (see Table 1).12 Several points stand out. First, displaced workers have lower pre-recession earnings than non-displaced workers of the same race. Second, Black workers have lower annual earnings than White workers, on average.13 Workers are around age 36 pre-recession (not shown in Table 1). Notably, Black workers are somewhat more likely to be displaced during recessions, consistent with prior literature.14

Having set the sample, the analysis is done using ordinary least squares regression.15 The dependent variable is log of earnings or an indicator of employment status. Essentially, the equation checks for differential pre-trends between displaced and non-displaced White workers five years prior to job loss and then estimates the effect of unemployment on their outcomes up to 10 years post-layoff, while also estimating the differential effect of displacement for Black workers.

Results

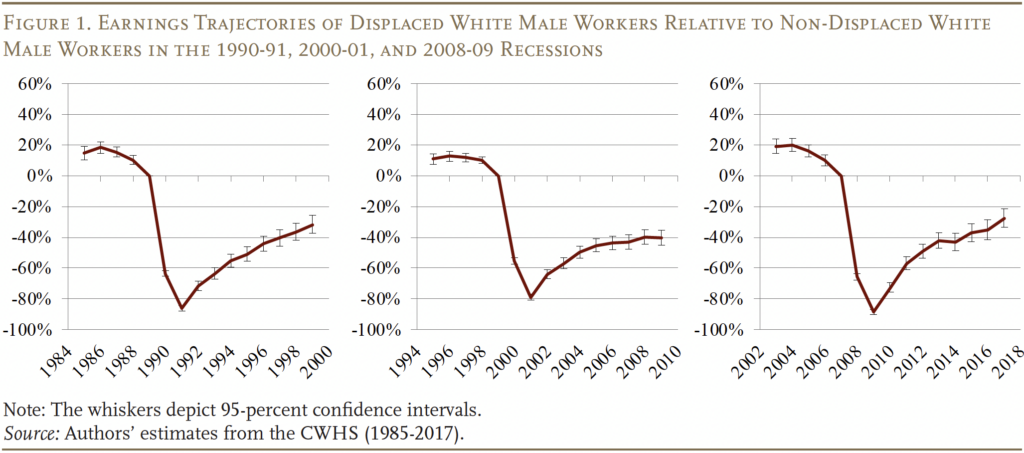

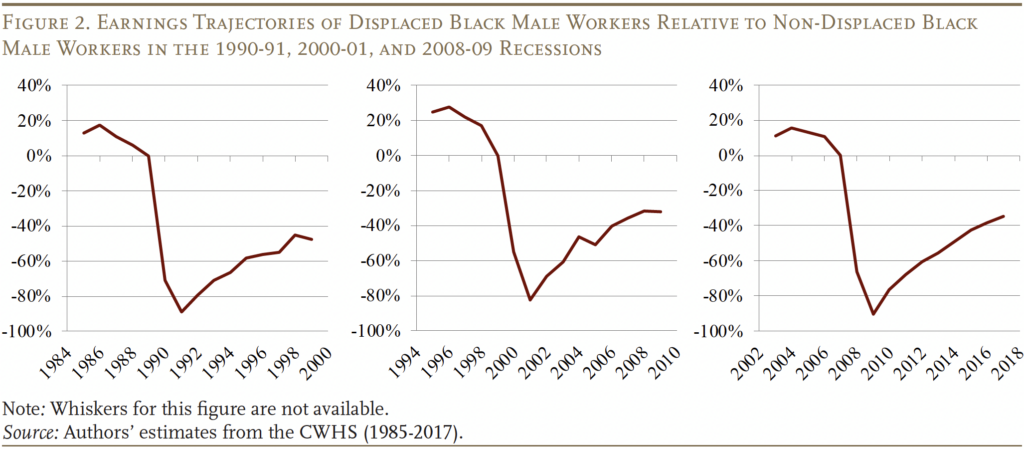

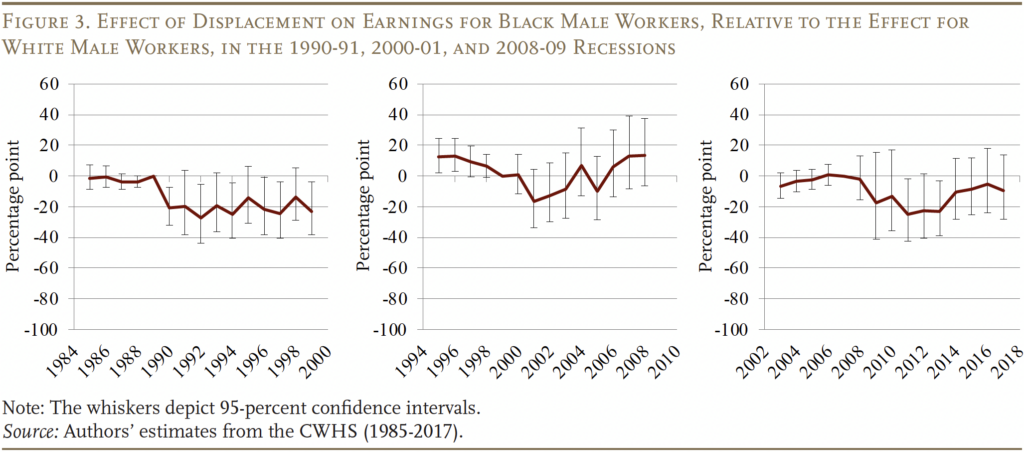

The regression results for the impacts of job-loss on earnings and employment by race are shown graphically in Figures 1-4.16

Effect of Job Loss on Earnings of White Workers

Figure 1 shows the effects of displacement on the earnings of re-employed White workers over the three recessions – that is, it compares White displaced workers with White non-displaced workers.17 The difference is shown in percentage terms relative to the year before displacement. All three recessions show remarkably similar patterns.18 First, White displaced workers consistently experience a 55- to 66-percent drop in earnings in the year of separation. In part, this drop reflects our definition of displacement as leaving a long-term employer and experiencing a change in earnings in the bottom 25 percent of separators in the year of displacement. A more meaningful measure of the loss is that earnings tend to fall even further for the displaced workers in the year after separation, bottoming out at declines of 79 to 88 percent. This later decline is no longer mechanical, but rather reflects a real and devastating impact of separating from employment. Second, these earnings losses are long-lasting: White displaced workers never recover within the 10-year window after each recession. By the final year, White displaced workers still have earnings 28 to 40 percent lower than they would have otherwise had.

Effect of Job Loss on Earnings of Black Workers

Figure 2 shows the earnings trajectories of Black displaced workers compared to Black non-displaced workers. Again, all three recessions show similar patterns. Much like White workers, Black displaced workers experience an 80- to 90-percent drop in earnings in the year following separation. On average, similar to White displaced workers, Black workers never recover within the 10-year window after each recession. By the final year, Black displaced workers still have earnings 32 to 47 percent lower than they would have otherwise had.

Differential Effect of Job Loss on Earnings of Black Workers

The key result of the analysis is the comparison of how displacement affects Black workers relative to White ones. Specifically, Figure 3 shows the impact of displacement for Black workers relative to their non-displaced Black counterparts, compared to the impact of displacement for White workers relative to their non-displaced White counterparts. The major conclusion is that Black workers did not suffer disproportionately from job loss in the long run. Yes, following the 1990-91 recession Black displaced workers experienced greater losses than their White counterparts, but these estimates are very imprecise. And importantly, the following two recessions show a pattern of recovery and no statistically meaningful difference in outcomes by race.

Effect of Job Loss on Employment of Black and White Workers

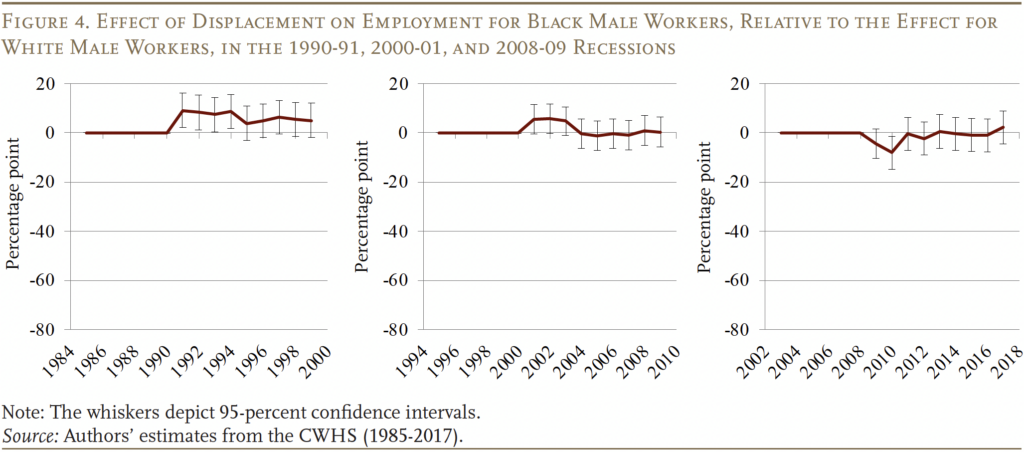

One further step is necessary before concluding that Black workers have not been hurt more than White workers from job loss, and that relates to employment. The findings above are based on the earnings experience of displaced workers who find a new job. If only 10 percent of Black people find new work, while 100 percent of White people are reemployed, the findings would not be meaningful. Therefore, Figure 4 shows the relative employment experience of Black and White workers. More specifically, it shows the difference in employment rates between displaced and non-displaced Black workers, compared to the difference in employment rates between displaced and non-displaced White workers. Interestingly, Black displaced workers actually experienced positive – albeit modest – “excess employment” during the first few years of the 1990-91 recession, before converging back to the same level as White displaced workers. The same pattern is discernible in the 2000-01 recession, although the difference is only marginally statistically significant, and disappears by the Great Recession. In other words, displaced Black workers do somewhat better in terms of employment relative to non-displaced Black people than their White counterparts. Thus, the conclusion of no difference in earnings trajectories for Black and White workers is a meaningful finding.

Conclusion

This study considers whether the effect of displacement on earnings is worse for Black than for White workers, focusing on men who were stably employed pre-displacement. The analysis combines a series of natural experiments with administrative earnings data from the SSA. Specifically, it compares the earnings trajectories of Black and White workers who were displaced during three recessionary periods to workers of the same race who were not displaced. The results show that displaced male workers experience large and persistent declines in earnings and employment relative to the counterfactual, regardless of race. While Black workers tend to lose more in percentage terms immediately following a job loss, this excess loss dissipates in the long run.

Nevertheless, Black workers still face significant labor-market headwinds as they start off at lower levels of earnings and employment than their White peers and face a disproportionate risk of displacement. Moreover, limiting the sample to those with five years of stable employment (as is standard in the literature on displacement) may produce a sample of Black workers who are more productive than the comparison sample of White workers. Hence, the findings may understate the extent of racial disparities in unemployment scarring. We leave this important question for future research.

References

Altonji, Joseph G. and Charles R. Pierret. 2001. “Employer Learning and Statistical Discrimination.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 116(1): 313-350.

Braxton, J. Carter and Bledi Taska. 2023. “Technological Change and the Consequences of Job-Loss.” American Economic Review 113(2): 279-316.

Cajner, Tomaz, Andrew Figura, Brendan M. Price, David Ratner, and Alison Weingarden. 2020. “Reconciling Unemployment Claims with Job Losses in the First Months of the COVID-19 Crisis.” Washington, DC: U.S. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Cooper, Daniel. 2013. “The Effect of Unemployment Duration on Future Earnings and Other Outcomes.” Working Paper 13-8. Boston, MA: Federal Reserve Bank of Boston.

Couch, Kenneth A. and Robert Fairlie. 2010. “Last Hired, First Fired? Black-White Unemployment and the Business Cycle.” Demography 47(1): 227-247.

Davis, Steven J. and Till von Wachter. 2011. “Recessions and the Costs of Job Loss.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 1-72.

Diette, Timothy M., Arthur H. Goldsmith, Darrick Hamilton, and William Darity Jr. 2018. “Race, Unemployment, and Mental Health in the USA: What Can We Infer About the Psychological Cost of the Great Recession Across Racial Groups?” Journal of Economics, Race, and Policy 1: 75-91.

Dwyer, Debra Sabatini and Olivia S. Mitchell. 1998. “Health Problems as Determinants of Retirement: Are Self-Rated Measures Endogenous?” Journal of Health Economics 18: 173-193.

Elvira, Marta M. and Christopher D. Zatzick. 2002. “Who’s Displaced First? The Role of Race in Layoff Decisions.” Industrial Relations 41(2): 329-361.

Farber, Henry S. 2003. “Job Loss in the United States.” Working Paper 9707. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Farber, Henry S., John Haltiwanger, and Katherine G. Abraham. 1997. “The Changing Face of Job Loss in the United States, 1981-1995.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. Microeconomics. 1997: 55-142.

Forsythe, Eliza and Jhih-Chian Wu. 2021. “Explaining Demographic Heterogeneity in Cyclical Unemployment.” Labour Economics 69: 1-15.

Guvenen, Fatih, Fatih Karahan, Serdar Ozkan, and Jae Song. 2017. “Heterogeneous Scarring Effects of Full-Year Non-Employment.” American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings 107(5): 369-373.

Jacobson, Louis S., Robert J. LaLonde, and Daniel G. Sullivan. 1993. “Earnings Losses of Displaced Workers.” American Economic Review 83(4): 685-709.

Kijakazi, Kilolo, Karen E. Smith, and Charmaine Runes. 2019. “African American Economic Security and the Role of Social Security.” Brief. Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

Lachowska, Marta, Alexandre Mas, and Stephen A. Woodbury. 2020. “Sources of Displaced Workers’ Long-Term Earnings Losses.” American Economic Review 110(10): 3231-3266.

Nekoei, Arash and Andrea Weber. 2017. “Does Extending Unemployment Benefits Improve Job Quality?” American Economic Review 107(2): 527-561.

Neumark, David. 2018. “Experimental Research on Labor Market Discrimination.” Journal of Economic Literature 56(3): 799-866.

Quinby, Laura D. and Gal Wettstein. 2025. “Is the Scarring from Unemployment Worse for Black Workers?” Working Paper 2025-8. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

_________. 2023. “Are Older Workers Capable of Working Longer?” Journal of Pension Economics and Finance.

Rose, Evan K. and Yotam Shem-Tov. 2023. “How Replaceable Is a Low-Wage Job?” Working Paper 31447. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Ruhm, Christopher J. 1991. “Are Workers Permanently Scarred by Job Displacements?” American Economic Review 81(1): 319-324.

Schmieder, Johannes F., Till von Wachter, and Stefan Bender. 2016. “The Effect of Unemployment Benefits and Nonemployment Duration on Wages.” American Economic Review 106(3): 739-777.

Stevens, Ann Huff. 1997. “Persistent Effects of Job Displacement: The Importance of Multiple Job Losses.” Journal of Labor Economics 15(1): 165-188.

Sullivan, Dan and Till von Wachter. 2009. “Job Displacement and Mortality: An Analysis Using Administrative Data.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 124(3): 1265-1306.

Thomson, Owen. 2021. “Human Capital and Black-White Earnings Gaps, 1966-2017.” Working Paper 28586. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2020. “Labor Force Characteristics by Race and Ethnicity, 2019.” Washington, DC.

U.S. Social Security Administration. Continuous Work History Sample, 1985-2017. Washington, DC.

von Wachter, Till M., Elizabeth Weber Handwerker, and Andrew K. G. Hildreth. 2009. “Estimating the ‘True’ Cost of Job Loss: Evidence Using Matched Data from California 1991-2000.” Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau, Center for Economic Studies.

von Wachter, Till, Jae Song, and Joyce Manchester. 2009. “Long-Term Earnings Losses Due to Mass Layoffs During the 1982 Recession: An Analysis using U.S. Administrative Data from 1974 to 2004.” Presented at the IZA/CEPR 11th European Summer Symposium in Labour Economics. Buch/Ammersee, Germany.

Endnotes

- Quinby and Wettstein (2025). ↩︎

- Cajner et al. (2020); Kijakazi, Smith, and Runes (2019); Elvira and Zatzick (2002); Couch and Fairlie (2010); and U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2020). ↩︎

- For example, the major papers in this field do not examine earnings losses by race, including Ruhm (1991); Jacobson, LaLonde, and Sullivan (1993); Stevens (1997); Farber, Haltiwanger, and Abraham (1997); Farber (2003); Davis and von Wachter (2011); von Wachter, Handwerker, and Hildreth (2009); von Wachter, Song, and Manchester (2009); Cooper (2013); and Lachowska, Mas, and Woodbury (2020). Guvenen et al. (2017) consider heterogeneity in scarring but not by race, and not in the spirit of the mass-layoff literature. Rose and Shem-Tov (2023) consider heterogeneity by race in a sample of low-wage workers and find results similar to ours in the more recent period, albeit with wide standard errors. Their analysis is complementary to the current setting in that we consider the more strongly-attached workers more typically considered to be vulnerable to scarring. ↩︎

- For a recent study on the former mechanism, see Braxton and Taska (2023). ↩︎

- Additionally, older Black workers may be more susceptible to unemployment-induced early retirement because they often suffer from worse health, and layoffs cause health shocks that push workers out of the labor force (Quinby and Wettstein 2023). Sullivan and von Wachter (2009) show that job displacement harms health and increases mortality. Dwyer and Mitchell (1998) argue that health is a stronger predictor of early retirement than economic factors. Furthermore, Diette et al. (2018) find that the adverse psychological effects of unemployment are worse for Black job seekers, which might further lead to greater impacts of job loss on Black workers. ↩︎

- Neumark (2018) shows that Black job-seekers receive fewer callbacks and interviews than similarly qualified White people. The duration of unemployment has a theoretically ambiguous effect on re-entry wages because a longer search facilitates a higher reservation wage, but also leads to skill erosion and “scarring” (Nekoei and Weber 2017 and Schmieder, von Wachter, and Bender 2016). Couch and Fairlie (2010) and Forsythe and Wu (2021) show that displaced Black workers spend more time job searching and are less likely to become re-employed. ↩︎

- Influential work by Altonji and Pierret (2001) shows that the earnings of Black workers have a lower return to tenure than those of otherwise similar White workers, suggesting that they are on different career ladders. One possible explanation is that educational disparities push Black workers into lower-paying jobs without a career ladder (Thompson 2021). ↩︎

- Full results for women are available in the Appendix of the full paper (Quinby and Wettstein 2025). ↩︎

- For example, the CWHS contains birth year, gender, and state of residence. Race is recorded on the application form for new Social Security numbers, and when beneficiaries interact with an SSA field office. Although often missing for younger birth cohorts, race is available for approximately 90 percent of the workers included in our analysis. However, the coding of Hispanic ethnicity has changed over time. ↩︎

- Although the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) dates the middle recession to 2001 only, we define it as occurring between 2000 and 2001 because earnings in the CWHS begin to decline in 2000. Conversely, while the NBER dates the Great Recession as starting in December 2007, labor market impacts began somewhat later and will be considered to start in 2008 in this analysis and are considered to persist through 2009. ↩︎

- This analysis cannot rule out the possibility that the treated group is less productive than the control group. However, comparing the treatment effect across Black and White workers should alleviate this bias since displaced Black workers are not likely to be less productive than displaced White workers. ↩︎

- For the comparable table for women, see Appendix Table A2 in Quinby and Wettstein (2025). ↩︎

- In contrast, among women in our sample, Black workers have slightly higher annual earnings than White workers for the earlier two recessions; only for women in the Great Recession do Black workers have lower annual earnings than White workers. This finding is consistent with the generally stronger attachment to the labor market among Black women versus White women, historically. ↩︎

- Again, this pattern is not apparent in the comparison of Black to White women. ↩︎

- The analysis framework follows Lachowska, Mas, and Woodbury (2020). For more details, see Quinby and Wettstein (2025). ↩︎

- Full regression results appear in Appendix Tables C1 and C2 of Quinby and Wettstein (2025). ↩︎

- When interpreting these estimates, it is important to keep in mind that the CWHS reports annual earnings. Particularly in the year of separation, these earnings losses thus also reflect parts of the year in which displaced workers had zero or very low earnings while looking for new employment or working odd jobs. However, the earnings estimates exclude workers who have zero earnings for the full year. ↩︎

- In addition to the patterns noted in the text, a pre-trend of one or two years is apparent. In some sense this pattern is reassuring, as it is consistent with almost all prior work in this field: the earnings of workers who are soon to be displaced tend to fall in anticipation of the displacement (known as “Ashenfelter’s dips”), though whether as a cause or a consequence of the subsequent separation is unclear. ↩︎