Retirees Tend to Be Happier than Younger People – Even If Their Finances Aren’t Great

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Older people have a great ability to adapt and cope.

Much of the work we do suggests that people are not saving enough for retirement. More specifically, since 2006 we have published our National Retirement Risk Index (NRRI), which uses the Federal Reserve’s triennial Survey of Consumer Finances to compare households’ projected replacement rates – retirement income as a percentage of pre-retirement income – with targets that would maintain their standard of living. Those households with a projected replacement rate that is more than 10 percent below the target are characterized as falling short. After almost two decades of kicking the tire, the NRRI continues to show that almost half of today’s working households will not have enough in retirement.

Some critics don’t like our model or assumptions; others say the results must be wrong because people report being perfectly content in retirement. Recently, as background for a bigger project, we looked at the happiness measures reported in the major longitudinal survey of older households (the Health and Retirement Study). This survey asks three recurring questions about satisfaction:

- Please think about your life-as-a-whole. How satisfied are you with it? Are you completely satisfied, very satisfied, somewhat satisfied, not very satisfied, or not at all satisfied?

- All in all, would you say that your retirement has turned out to be very satisfying, moderately satisfying, or not at all satisfying?

- Thinking about your retirement years compared to the years just before you retired, would you say the retirement years have been better, about the same, or not as good?

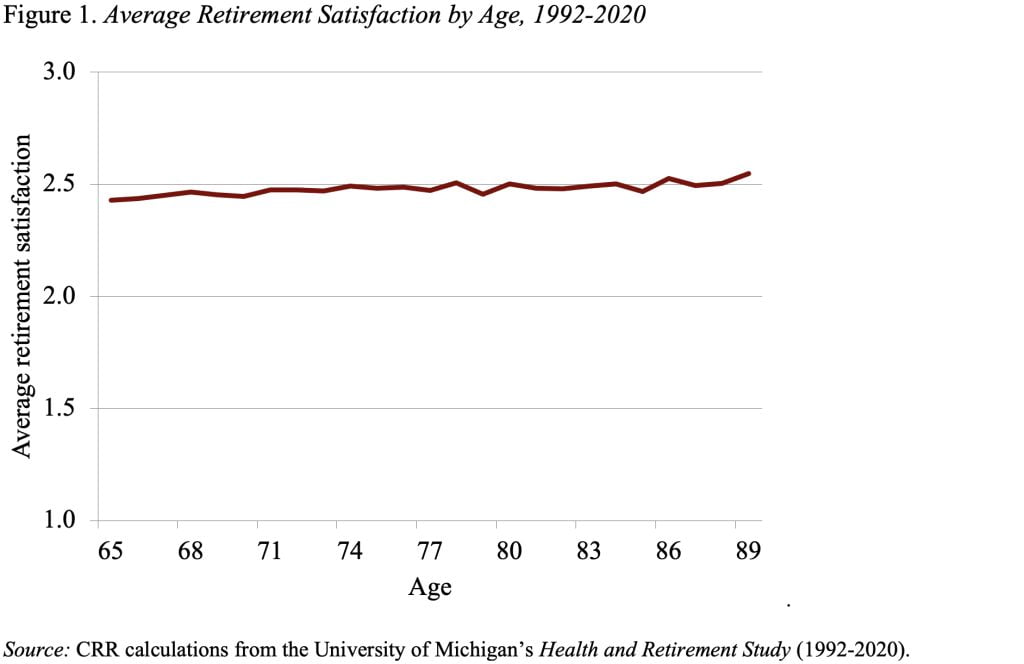

We focused on question #2, where the responses were coded as follows: 3 = “retirement is very satisfying; 2 = “moderately satisfying,” and 1 = “not at all satisfying.” The results suggest that not only are the levels of satisfaction high, but they are improving as people age (see Figure 1).

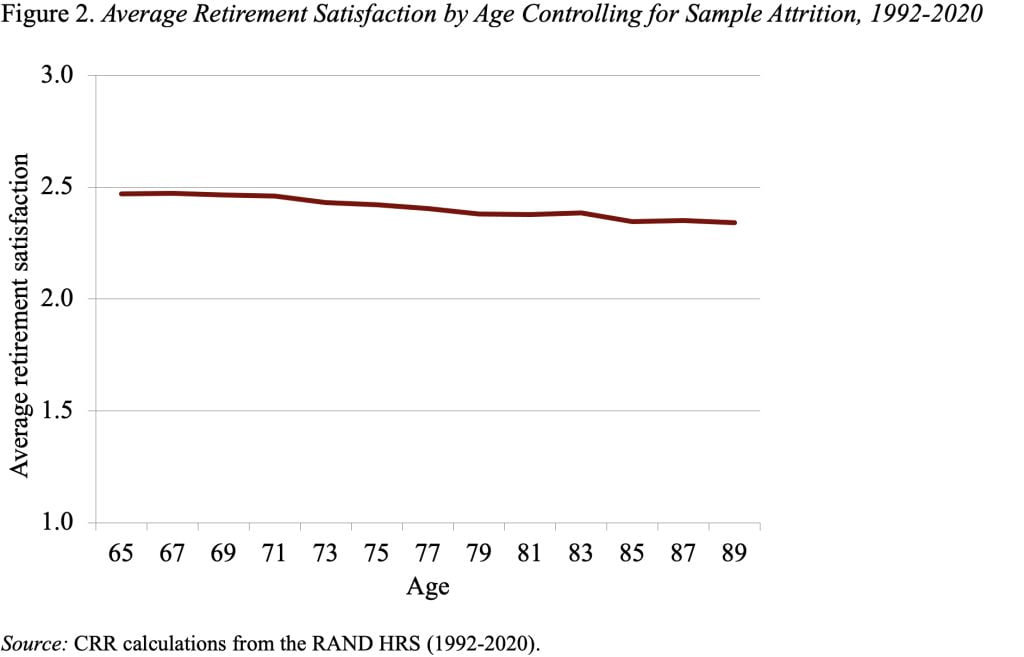

That picture is not quite fair because those who find retirement “not at all satisfying” tend to be poor and sickly and die earlier than the others. When they leave the sample as they die, it raises the level of satisfaction for the remaining group. So maybe controlling for this attrition would change the picture. Indeed, it does a little (see Figure 2). The line slopes down with age, but the level of satisfaction remains well above a 2 – somewhere between “moderately satisfying and very satisfying.” That does not seem like a situation where retirees are in dire straits.

So, what’s going on here? It turns out that older people are generally happier than their younger counterparts, and a whole body of psychological literature is devoted to trying to explain older people’s positivity. It appears that older people have a greater ability to insulate their thoughts and emotional reactions from negative situations and have a great ability to adapt and cope.

Candidly, I find that myself as an older person. The oriental rug in the entryway of our house has worn thin generally, and has actually developed a fairly large hole. Twenty years ago, we would have shopped for a new rug, now we simply put colored paper underneath the hole!

The bottom line is that it is probably not possible to assess the adequacy of savings by asking older people about their level of satisfaction or happiness. They are all really happy. Yet surveys repeatedly show that when people are asked what they should have done differently, they often reply: “I should have saved more” or “I should have started saving earlier.”

We’re off to find other metrics to figure out what’s going on.