Rising Debt among Older Households Is a Serious Problem

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

But not all “high-risk” borrowers are alike, so we need a variety of responses.

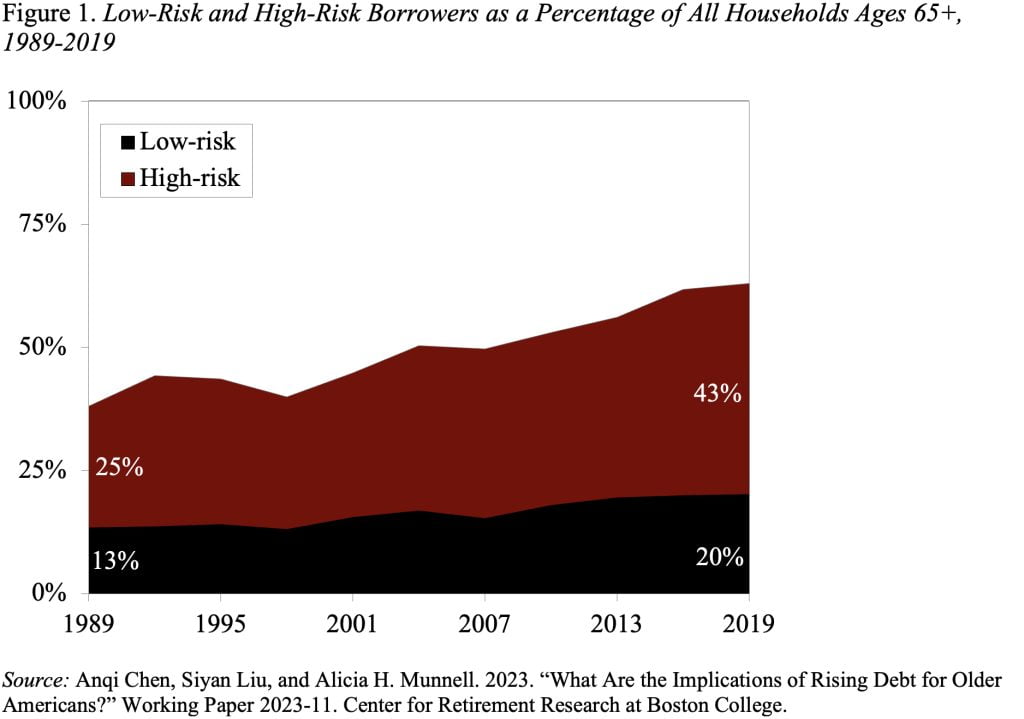

Policymakers and researchers have been fretting that the share of older Americans with debt has risen from 38 percent to 63 percent since 1990. Having debt, however, doesn’t have to be a bad thing. For example, households that take out a low-interest mortgage to buy a home, which typically appreciates, are likely making a savvy choice. In contrast, households that carry unpaid credit card balances could see their debt snowball, leading to financial distress. In a recent study, my colleagues and I tried to sort out what share of households with debt were at “high risk” and “low risk” of financial hardship and whether those at high risk generally looked the same or fell into distinct groups.

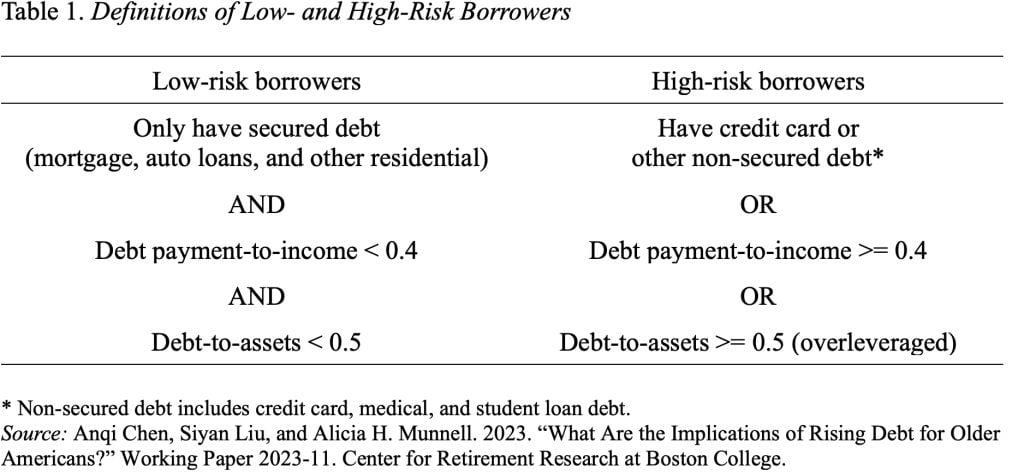

The first step was determining how many of these households were at high risk. The factors – secured vs. unsecured debt, debt payment-to-income ratio, and debt-to-assets ratio – are commonly used by lenders and other researchers (see Table 1). Households with any revolving credit card debt are classified as “high risk” since many of these borrowers could experience bad outcomes, even though the other debt measures would not capture them.

The results of the classification exercise show that overall growth is driven by high-risk households (see Figure 1).

In thinking about policy solutions, it’s essential to figure out how these high-risk households got in trouble. To do that, we used a technique that revealed four clear subgroups of high-risk borrowers.

- The largest group (33%) consists of “financially constrained” households, which have low levels of wealth, are often overleveraged, and struggle with the essentials. This group is borrowing just to get by.

- The second subgroup (26%) consists of “credit card borrowers,” which includes middle-wealth households with no apparent need to borrow.

- The third subgroup (19%) is low/middle-wealth households whose housing debt payments consume over 40 percent of their income. This group is also disproportionately non-White.

- The last group (23%) is “wealthy spenders.” Despite being in the top third of the wealth distribution, about a quarter of their income goes to debt payments, about 80 percent have credit card debt, and over a third have second homes.

What can be done to reduce the financial vulnerability of high-risk borrowers? Given their diverse characteristics, no one-size-fits-all solution exists.

- Debt counseling and consolidation may help the “financially constrained” households, but many struggle to meet basic needs, so they need more resources.

- “Credit card borrowers” could benefit from traditional financial counseling and legislation requiring credit card issuers to provide better information to consumers.

- Households with “too much house” would best be served by programs that reduce their housing burden, such as refinancing or downsizing.

- Finally, since many “wealthy spenders” have a second home, selling it is one way to manage their debt.

The key takeaways from this study are: 1) the growing debt among older households is not a benign phenomenon; and 2) the diverse characteristics of high-risk borrowers require a variety of policy responses.