“Rothification” Is Likely to Reduce Retirement Saving

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Simple model suggests more saving, but real world frictions likely to produce less saving.

For the record, we would not be discussing shifting from traditional to Roth 401(k)s except that Congress is looking for additional revenue to offset its proposed tax cuts over the next 10 years, the timeframe used for considering legislation.

As background, the main difference between traditional and Roth 401(k)s is the timing of taxes. Contributions to a traditional 401(k) account are not included in the employee’s income and earnings are not taxable currently, while distributions at retirement are treated as taxable income. Contributions to a 401(k) Roth account are made out of the employee’s after-tax income, earnings are not taxable currently, and distributions generally are not taxable.

These provisions mean that with the traditional plans where the contributions are deductible, the Treasury takes an up-front hit but recoups the money when accumulations are withdrawn in retirement. With the Roth approach, the Treasury forgoes no revenues in the short run but sees no revenues from withdrawals at retirement. So switching from the traditional to Roth format would boost revenues in the near term and reduce them in the future.

Thus, the proposal to switch from traditional to Roth 401(k)s is nothing more than a budget gimmick. Unfortunately, it is likely to have real-world consequences. A simple model suggests that savings could increase, but a more realistic assessment suggests otherwise.

The simplest interpretation suggests that savings increase.

- Assume that 50 percent of people plan to contribute the same dollar amount to a Roth 401(k) that they previously contributed to a traditional 401(k). This group will have more after-tax savings, because a Roth contribution has already been taxed, while the same dollar contribution to a traditional 401(k) has not. Even if people somewhat reduce their non-qualified saving, they will come out ahead.

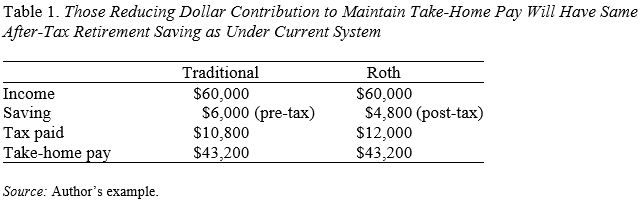

- Assume the other 50 percent plan to decrease their contributions in order to maintain their take-home pay. This group will have the same after-tax savings. Table 1 illustrates this point for someone earning $60,000 a year, with a constant tax rate of 20 percent, who contributes 10 percent to a traditional 401(k). In this world, the after-tax contribution of $4,800 will yield the same after-tax wealth at retirement as the pre-tax contribution of $6,000 (once taxes are taken into account).

Overall, then, with half of people saving more and the other half saving the same, savings would increase under the Roth 401(k).

Irrational responses could lead people to save less.

However, real-world behavior often differs from what economic theory would predict. In this case, several factors could result in less overall saving:

- The assumption that 50 percent of individuals maintain their dollar contributions might hold in a frictionless world where they did not have to re-enroll. But, when switching to a Roth, employees will have to “reset” their contributions with their employers. During this process, they might totally reconsider their contribution rate, so the assumption that 50-percent will maintain their contributions may well be too high.

- The 50 percent who were assumed to decrease their savings could overreact to the switch to a Roth. For example, they could feel that no tax deferral is equivalent to no tax advantage at all, in which case they could cut their contributions dramatically.

- People may be more tempted with a Roth as opposed to a traditional account to cash out when they change jobs, since they would not pay income taxes and penalties on the money that they had contributed.

- A few plans sponsored by small business owners seeking immediate deductions may close.

In short, a mandatory shift from conventional to Roth 401(k) plans is a really bad idea. In principle, a retirement saving system based on Roth 401(k)s could work fine. But transitioning people from one type of saving vehicle to another will create confusion and lead to unintended consequences that undermine retirement security. And the people who are most likely to get hurt are low-wage workers and those with liquidity constraints, because they have less ability to pay taxes on their savings upfront.

If Congress cannot do anything constructive on the retirement savings front, then let’s encourage it to at least do no harm.