Why Tax Reform Could Take Away Some of the Benefits of Retirement Saving

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Changes to the taxation of capital income can have a big effect.

Retirement saving in typical employer plans – both defined benefit pension and 401(k) plans – is tax advantaged because the government taxes neither the original contribution nor the investment returns until they are withdrawn as benefits at retirement. If the saving were done outside a plan, the individual would first be required to pay tax on their earnings and then on the returns from the portion of those earnings invested. Deferring taxes on the original contribution and on the investment earnings is equivalent to receiving an interest-free loan from the Treasury for the amount of taxes due, allowing the individual to accumulate returns on money that they would otherwise have paid to the government.

Under a Roth 401(k), initial contributions are not deductible, but interest earnings accrue tax free and no tax is paid when the money is withdrawn. Although the traditional and Roth 401(k)s may sound quite different, in fact they offer virtually identical tax benefits.

While the provisions are clear, the value of the tax preference depends on the tax treatment of investments outside of 401(k)s. The intuition is clearest when considering stock investments inside and outside of a Roth 401(k), as in both cases the investor pays taxes on his earnings and puts after-tax money into an account. Assume the tax rate on capital gains and dividends is set at zero. In the Roth 401(k) plan, he pays no taxes on capital gains as they accrue over time and takes his money out tax free at retirement. In the taxable account, he pays no tax on the dividends and capital gains as they accrue and takes the money out tax free at retirement. In short, the total tax paid under the Roth and the taxable account arrangement is identical.

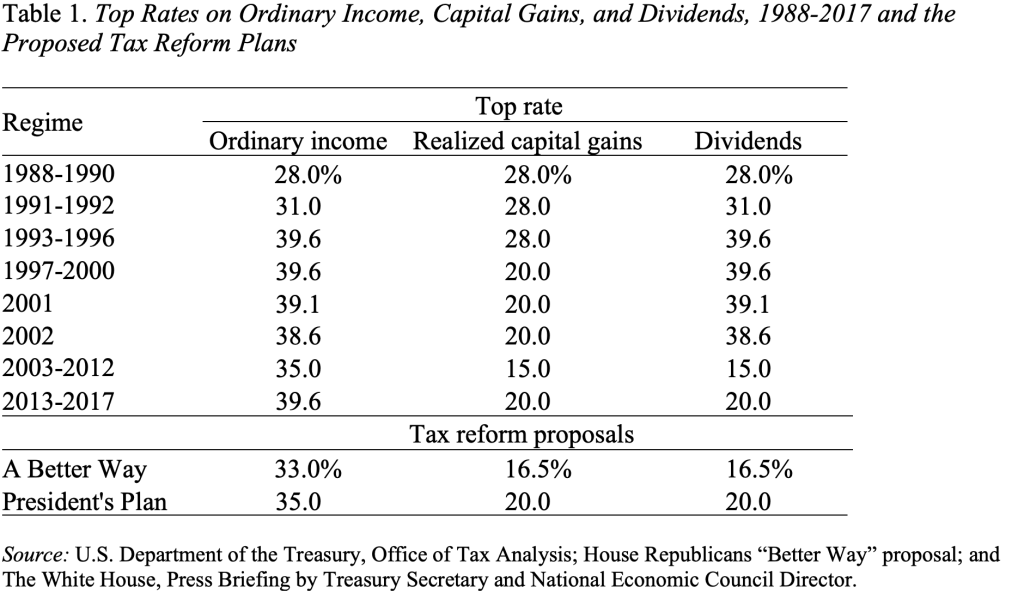

How close is the assumption of a “zero” tax rate to the real world? Table 1 summarizes the maximum tax rates applied to capital gains and dividends since 1988. The 1986 tax reform legislation set the tax rate on realized capital gains and dividends equal to that on ordinary income. The capital gains tax rate became preferential in 1991, not because it changed but because the rates of taxation of ordinary income and dividends increased. Subsequently, Congress explicitly reduced the tax rate on capital gains effective in 1997 and dividends effective in 2003. Going forward, the Republican House tax plan (as discussed in “A Better Way”) would reduce rates on capital income whereas the President’s plan would keep them unchanged.

The bottom line is that financial services firms that are worried about the favorable treatment of 401(k)s should keep their eyes on the taxation of capital income outside of retirement plans as much as on the tax preferences themselves.