The Social Security Fairness Act Is a Terrible Piece of Legislation – Here’s How to Fix the Problem

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Looking to the underlying problem — uncovered state and local workers.

Every analyst who knows anything about Social Security agrees that the Social Security Fairness Act, signed by President Biden on January 5, is a terrible piece of legislation. It simply gives away money to some state and local workers – those who will now benefit unfairly from the progressivity of the system’s benefit formula and from benefits designed for non-working spouses. Eliminating the Windfall Elimination Provision (WEP) and Government Pension Offset (GPO) makes Social Security less – not more – fair. For specifics of the windfalls, see my recent blog post or the most detailed example ever from my friend Andrew Biggs.

Yes, the case for the WEP and GPO involves some understanding of Social Security. Yes, the provision could have been better designed. Yes, it infuriated state and local employees. But these adjustments were designed to fix a real equity issue. How could any well-informed member of Congress vote to eliminate them – wasting money, accelerating the exhaustion of the trust fund, and making the 75-year financing hole bigger?

Personally, I accept my share of the failure of experts to make a compelling case to the public and to the staff and members of Congress for the needed adjustments. But I think it’s time to accept defeat and move on. The most constructive thing to do at this point is to fix the source of the problem – that is, extend Social Security coverage to the 25-30 percent of state and local workers who are not covered by Social Security.

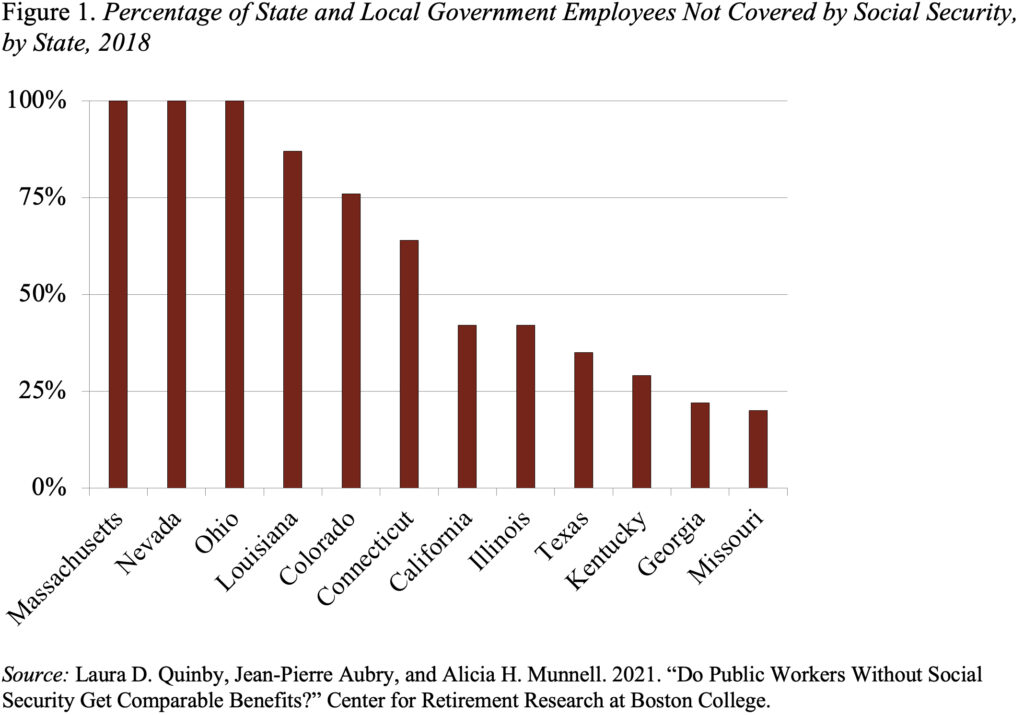

A little background. The Social Security Act of 1935 excluded state and local workers from mandatory coverage due to constitutional concerns about whether the federal government could impose taxes on state governments. As Congress expanded coverage to new groups of private sector workers, it also passed legislation in the 1950s that allowed states to elect voluntary coverage for their employees. While many states did join, our calculations show that 26 percent of the state and local workforce in 2022 – 5 million workers – still are not covered by Social Security. The bulk of uncovered workers (77 percent) reside in seven states – California, Colorado, Illinois, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Ohio, and Texas. In California, Illinois, and Texas, uncovered state and local workers constitute 42 percent, 42 percent, and 35 percent of the total, respectively (see Figure 1). In Massachusetts, Ohio, and Nevada, no government workers are covered by Social Security.

If all state and local workers were covered, the need for equity adjustments, such as the WEP and GPO, disappears. Moreover, expanding coverage would ensure that all workers are paying their share of the legacy costs associated with the startup of Social Security and are contributing to the redistributive elements in the program. At the same time, extending coverage would also improve the retirement income of many state and local workers, who are reliant on public pension plans less generous than Social Security, and provide them with important ancillary protections that they currently lack, such as spousal and survivor benefits. Social Security also offers comprehensive disability insurance.

Of course, a proposal to extend coverage sparks the predicable outcry from public employee unions and state/local governments regarding the costs. Virtually all proposals for mandating Social Security coverage are limited to new employees only, which would ease the transition. And the magnitude of the ultimate cost depends crucially on how plan sponsors respond to the introduction of Social Security – that is, states and localities are unlikely to simply add Social Security on top of existing provisions. We need some careful estimates of the range of possible outcomes.

On the other hand, extending coverage to the 5 million uncovered workers would contribute to closing Social Security’s 75-year deficit. The actuaries’ most recent estimate is that extending coverage would reduce the 75-year deficit from 3.50 percent of taxable payrolls to 3.35 percent.

Let’s forget about the WEP and GPO band-aids and fix the underlying problem. It makes no sense to have a national social insurance system with redistributive features that allows 5 million workers to not participate. That’s an easy argument. Let’s start crunching the numbers so that extending coverage is one of the proposals on the table when the time comes for Congress to design a package to solve Social Security’s financial shortfall.