This Benefit Makes Secure 2.0 Worth It

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

The new credit provides a real chance at enhancing the retirement savings of low and middle earners.

The inclusion of the new Saver’s Credit in the Secure 2.0 Act provides some balance to a piece of legislation that previously had primarily provided extensive goodies to high earners in the form of delayed required minimum distributions, provisions for catch-up contributions, and more. Despite my enthusiasm for the new credit, I do have some questions about the mechanics.

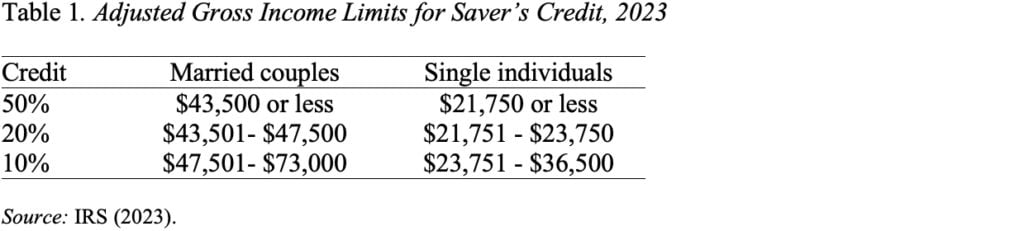

A saver’s credit designed to help lower and middle-income Americans save for retirement has been on the books for some time. Under current law, depending on adjusted gross income (AGI), a household can claim a credit for 50 percent, 20 percent, or 10 percent of the first $2,000 contributed during the year to a retirement account (see Table 1).

In theory, workers could gain a lot from the Saver’s Credit. A married couple with combined income of $43,500 who each contribute $2,000 to his/her retirement plan are eligible for a $1,000 credit each, for a total of $2,000. That is, they pay $2,000 less in federal income taxes than they would have otherwise.

In practice, the Saver’s Credit does not work so smoothly. First, the credit is nonrefundable, which means that it can reduce the required tax repayment to zero but not below. So, if the couple had a tax liability of only $750, their credit would be limited to that amount. Second, because of interaction with the Child Care Credit, the Saver’s Credit is often not usable for taxpayers with children. Finally, the design is a little crazy. As couples move from an AGI of $43,500 to $43,501, their credit rate drops from 50 percent to 20 percent. Finally, many people do not know about the Saver’s Credit.

SECURE 2.0 dramatically changes the Saver’s Credit.

- First, it creates one credit rate of 50 percent, as opposed to the tiered percentages as income rises, which – at a minimum – makes the credit less complicated and confusing.

- Second, it makes the Saver’s Credit refundable. That is, it changes it from a credit used to reduce a tax liability to a government matching contribution that will be deposited in the taxpayer’s retirement plan. So, if a qualified individual puts $2,000 into a retirement account, the government will provide a matching contribution of $1,000.

- Finally, it provides money so that the Treasury can increase public awareness about the availability of the credit.

A government match for low and middle earners is a wonderful development in general, and will be particularly helpful in enhancing balances in the state-initiated Auto-IRA programs, up and running in California, Illinois, Oregon, and elsewhere.

Here’s what I don’t quite understand, though. How is the government going to know where to send the match and how will it move the funds mechanically? How is the credit, which is a pretax contribution, going to mesh with the state auto-IRA programs, which are built on a Roth model? Perhaps these hurdles explain why the new Saver’s Credit does not take effect until 2027! Since we recently put the Webb Telescope a million miles from Earth to explore the history of the universe, we should be able to figure this out in four years!!