Could Tontines Be an Alternative to Annuities?

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Costs are lower than an annuity and you just need to stay alive to claim.

We have a new brief on “tontines.” People get quite excited about this topic, so it’s good to know what they are talking about.

A big challenge facing retirees is how to draw down their nest egg in retirement. The main consideration is insuring against “longevity risk” – the possibility of outliving one’s savings – without unduly restricting spending. One solution is to buy an annuity, but few people actually do it. One – among many reasons – is that annuities are expensive. For this reason, some policy experts have begun advocating an alternative form of longevity insurance – called a “tontine.”

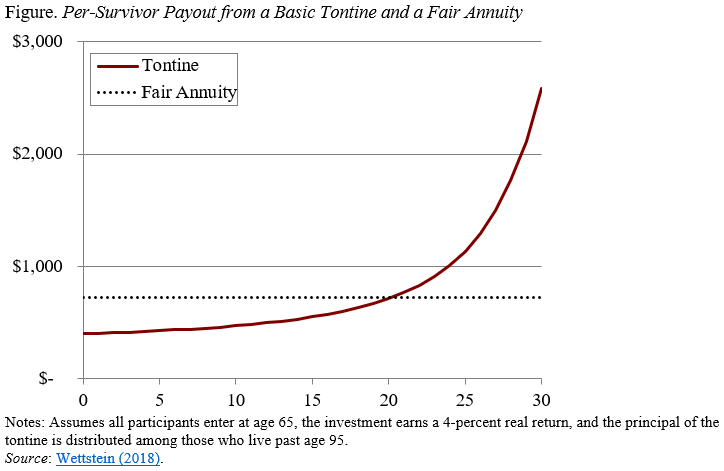

A simple tontine (named after 17th century Italian financier Lorenzo de Tonti) involves a group of investors who each buy a share of a fund that pays out returns to the remaining living members. The original tontines were administered by monarchs, who used the pool of money from tontine investors to finance wars or pay off debt. Tontine participants were willing to loan money at a lower interest rate than traditional lenders for the possibility of collecting higher payouts over time. Although, historically, tontines were not used for retirement, the current conversation among economists and finance experts focuses on the potential of tontines to offer longevity insurance for retirees. Payouts are ensured as long as one of the participants survives and increase for surviving participants as other participants die (see Figure). For comparison, the figure also displays the payout from a fair annuity with the same initial investment.

While tontines and annuities both provide lifetime income, they differ in cost. Annuity premiums tend to be relatively high because the insurance company bears the risk that their customers on average live longer than expected, due to, say, a cure for cancer. To insure against such a risk, the provider needs to keep a buffer of assets to maintain the promised level of payments.

Tontines do not provide insurance against this “systemic longevity risk” and instead pass it on to the customer instead. If tontine participants generally live longer than expected, each one would receive smaller payments than originally anticipated. The provider’s job is thus simple and does not even require an insurer, just an administrator.

Moreover, a modification to the simple tontine could fix the payment pattern so that very old people don’t get the largest amounts. Basing payments on the group’s overall survival probability would ensure that payments held steady over the years. As investors die, the total number of fixed payments would naturally decline, leaving enough funds in the pool to continue the equal payments.

Because of financial shenanigans that occurred in the United States in the early 20th century, an early version of tontines – which involved a large build-up of assets rather than regular benefits – was ruled illegal. It remains unclear whether regulations barring the tontines of the early 20th century would apply to a tontine as described above.

It also remains unclear whether people would want tontines. Yes, they are cheaper than annuities – because they provide less insurance – but it is not clear whether cost is the key factor hindering the demand for lifetime income options.