What Are Members of Both Parties Thinking?

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

If we don’t want to cut programs, then we need big tax increases

The U.S. fiscal challenge is pretty straightforward. Revenues in 2012 equal 16 percent of our nation’s output and spending (excluding interest) is 22 percent. Deficit spending makes sense in a weak economy, but even once the economy recovers revenues will fall short of expenditures. And that gap gets larger and larger over time, as an increasing portion of the population retires and becomes eligible for Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid. Year after year of deficits produces an enormous build up in debt and interest expense. Under the Congressional Budget Office’s “Extended Alternative Scenario” for 2037, interest expense amounts to 9.5 percent of GDP and outstanding debt equals two times GDP.

The only way to close the gap between revenues and expenditures is to raise revenues, reduce expenditures, or adopt some combination of the two. Whatever the choice, the magnitudes of the required changes are large (much larger than the amounts under consideration in the budget negotiations). And while all the changes do not have to be made immediately, the longer they are postponed the larger they need to be. The only way to decide how much to do on the revenue side and how much to do through taxes is to evaluate how the government is currently spending our money.

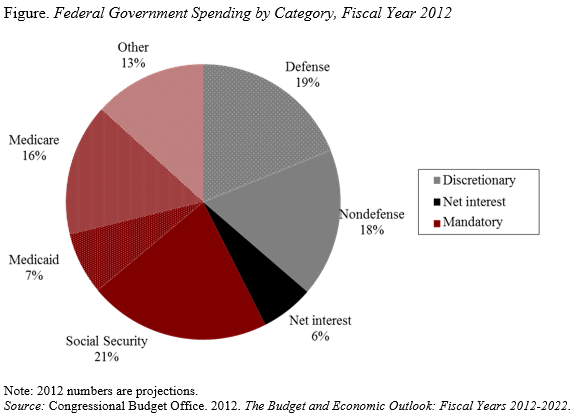

So let’s take a quick look at the budget. Federal government spending falls into three broad categories (see Figure). The first is mandatory programs, such as Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, and other programs in which spending is determined by rules for eligibility, benefit formulas, and other parameters rather than by specific appropriations. The second category is discretionary spending, which is controlled by annual appropriations. Roughly half of discretionary spending consists of spending on defense and the other half on non-defense programs, such as education, transportation, and agriculture. The final category is interest payments on the nation’s debt.

The areas that I know best are those related to retirement – Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. Given that the average household approaching retirement (age 55-64) has only $120,000 in its combined 401(k)/Individual Retirement Account, policymakers should be careful before they cut much from Social Security. Cutting Medicare by raising the age of eligibility, increasing the premium for Part B, and/or raising co-payments and deductibles simply shifts the burden to individuals. Eliminating ineffective and inappropriate treatments is the best way to reduce Medicare spending, and this issue is being addressed through the Affordable Care Act. Any progress in controlling health care costs would also restrain Medicaid spending. In short, I don’t see much to cut in the mandatory programs.

As a non-expert, I suspect that intelligent cuts could be made to the defense budget without eroding our security. Non-defense discretionary, however, has pretty much been cut to the bone, and it would be difficult to generate much additional savings without hurting really poor people.

Thus, I know where I stand. I value most of what the federal government provides and am willing to pay substantially higher taxes to cover the cost of these programs. My frustration with the President is that he suggests that the nation can finance its programs by raising taxes only on the rich. That is not true. We all need to pay more.

At the same time, the Republicans claim they want smaller government. Yet they cannot come up with specific proposals to cut the budget. My sense is that their reluctance is more than a negotiating strategy, but rather reflects the fact that our government spending is not really “out of control.” Republicans suggest means-testing Medicare, raising the age of eligibility for Medicare benefits, or changing the Social Security cost-of-living adjustment, all of which are bad policy but more importantly would raise little money. They can’t make bigger proposals because they don’t see any place to make big cuts.

If we as a nation do not want to make big cuts on the spending side, then we are going to need big increases in revenue. Let’s not play games. Tell the American people how much their package of programs costs and then they can make informed decisions about whether they are still willing to pay for them.