401(k) Tax Subsidy and Matches Favor Higher Earners, Often White

The Social Security program was designed to support lower-income retirees more by replacing a larger share of their past earnings than higher earners receive. But the subsidies that encourage workers to save for retirement tilt in the opposite direction.

For this reason, White workers – who tend to earn more than Blacks and Hispanics – receive a disproportionate share of the employer matches and federal tax breaks embedded in 401(k)-style savings plans, according to a study of workers with these plans.

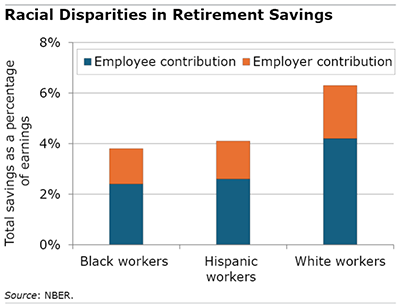

White workers start out saving more. They contribute 4.2 percent of their earnings, on average, and their employer matches add another 2.1 percent for a total saving rate of roughly 6 percent, the researchers at MIT, Harvard, Yale, and the U.S. Census Bureau find.

Black and Hispanic workers with plans, who make less, also contribute less: about 2.4 percent of their earnings. Their employers add about 1.5 percent, for a total of around 4 percent of their earnings.

This shortfall in Blacks’ and Hispanics’ savings rates is just one of several ways in which our 401(k) retirement system favors higher-income, largely White, workers.

Retirement plans are “one of the best, if not the best, financial investment opportunities available to build wealth,” the researchers explain. But the subsidy system, which “rewards those who can, and do, save more for retirement,” is a large factor in the yawning wealth gap in this country between White workers and their Black and Hispanic counterparts.

Employers’ and workers’ combined contribution rates for 401(k)s are also less for Blacks and Hispanics – by 14 percent and 7 percent, respectively – even when the researchers compare them to White workers who are similar in numerous respects, including being in the same income bracket. More detailed analyses show there are other reasons for the gap between White workers and Black and Hispanic workers.

For example, age differences drive saving. Black and Hispanic workers are younger, on average, than Whites. But retirement is a bigger priority for older workers, who have fewer competing financial demands on them. Other variations could be due to racial differences in tenure on the job – knowledge about the employer’s 401(k) benefit can increase over time – and to education, which increases financial literacy. Family advantage plays another role: workers with higher-income parents contribute more and have fewer premature withdrawals.

But even when the researchers accounted for these differences, the racial gaps in savings “remain large” they said.

As a result of the savings gaps by race and ethnicity, the tax subsidies for 401(k)s, which cost the federal government more than $200 billion a year, also disproportionately go to Whites.

When workers save in a traditional 401(k), the contribution is deducted from their taxable income, reducing what they owe at tax time. But because Black workers save less, they receive smaller tax subsidies – 31 cents for every dollar of tax breaks a typical White worker receives. Hispanic workers receive about 62 cents.

Early withdrawals from 401(k)s are another source of inequities. The IRS requires workers under age 59½ to pay a tax penalty equal to 10 percent of the withdrawal for dipping into their retirement savings prematurely. The penalty is on top of income taxes on that withdrawal.

Despite the penalties, 23 percent of Black workers under age 55 withdraw money from their 401(k)s – double the rate for White workers. Hispanic withdrawals are slightly higher than Whites’. The researchers also found indications that Black savers more often withdraw money because they don’t have as much liquidity in their checking and savings accounts as White workers with similar incomes.

They propose that more progressive policies would iron out some of the racial and ethnic disparities. Rather than basing the tax subsidy on how much workers save, for example, all workers could instead receive a contribution to the savings plan by the government equal to a set percentage of their earnings.

But the main goal of this study is to document how much retirement savings incentives contribute to inequalities in retirement wealth.

To read this study by Taha Choukhmane, Jorge Colmenares, Cormac O’Dea, Jonathan Rothbaum, and Lawrence Schmidt, see “Who Benefits from Retirement Saving Incentives in the U.S.? Evidence on Racial Gaps in Retirement Wealth Accumulation.”

The research reported herein was performed pursuant to a grant from the U.S. Social Security Administration (SSA) funded as part of the Retirement and Disability Research Consortium. The opinions and conclusions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not represent the opinions or policy of SSA or any agency of the Federal Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of the contents of this report. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply endorsement, recommendation or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof.

Comments are closed.

You could follow up this blog with a blog saying “Social Security favors lower earners, often Black.” Both are what you would expect from a system in which Social Security gives higher replacement to lower earners and higher earners need to reply on 401(k) plans for a larger share of their retirement income.

Regardless of race, pensions and retirement funds are based on what income is earned and what one can contribute to their retirement. It has always been this way. I can make a lot of money; however, if my expenses exceed what I make, then no matter how much I make, I would have less to contribute if anything. Social Security is the best example of this. The more one makes, the larger the benefit. Stop basing this on race. Women also make less than men do, and that is a fact.