Do High-cost Areas Produce Lower Social Security Replacement Rates?

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

And do people respond by saving more, retiring later, or moving?

My colleagues and I have always had this notion that, because wage levels vary across the country, workers in high-cost areas would receive lower replacement rates under Social Security’s progressive benefit formula than otherwise identical workers in low-cost areas. This variation in replacement rates could then cause those in high-cost areas to retire later, save more, or be more likely to move in retirement. So, I was delighted when Laura Quinby and Gal Wettstein decided to investigate this issue more carefully.

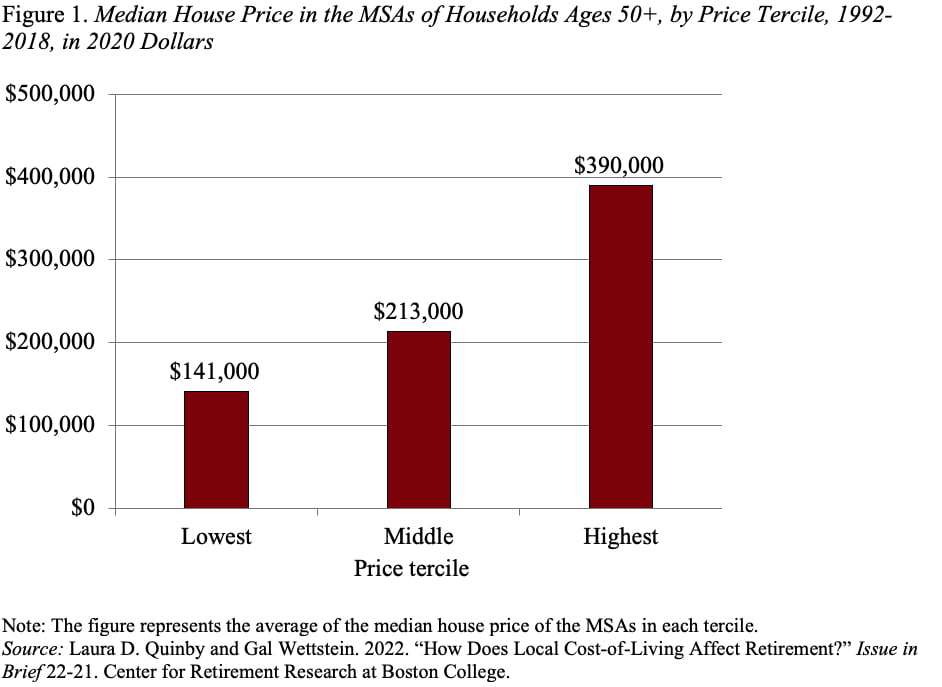

The authors use housing costs as a proxy for cost-of-living, since U.S. households spend a large share of their budget on housing, and they focus on Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs), which capture major population centers and their suburbs. The data show that households in the bottom two terciles experience relatively similar housing prices, whereas those in the top tercile face prices that are around double (see Figure 1).

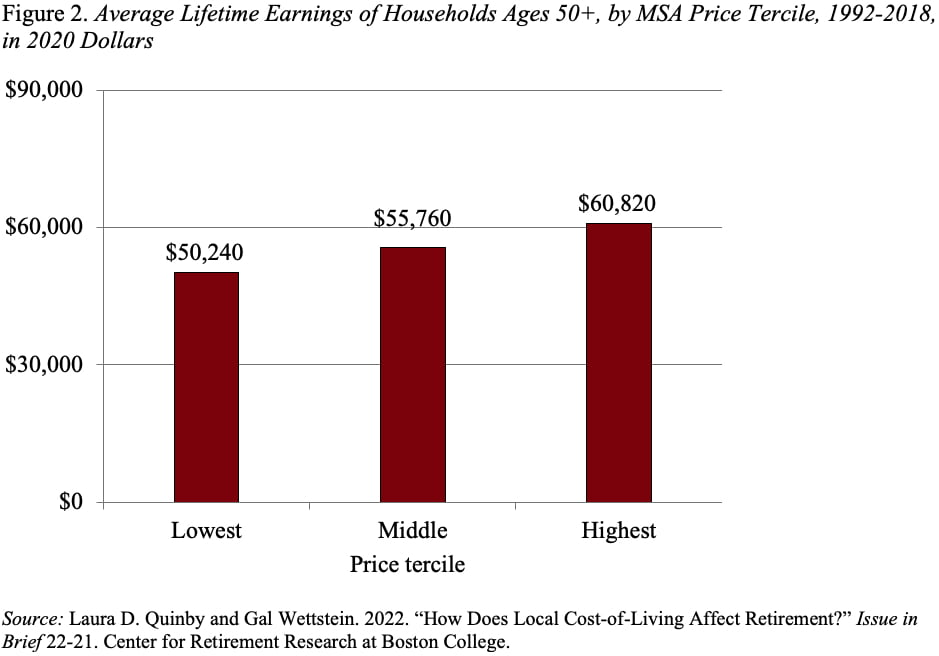

To attract workers to areas with high house prices, firms have to offer more wages and/or fringe benefits. The variation in wages, however, turned out to be modest – only a 20-percent increase in average household earnings between the bottom and top price terciles (see Figure 2). While earnings need to rise only by about a third between the bottom and the top terciles to fully offset the cost of financing housing, the numbers suggest that older households are only partly compensated for local housing costs, at least in terms of wages.

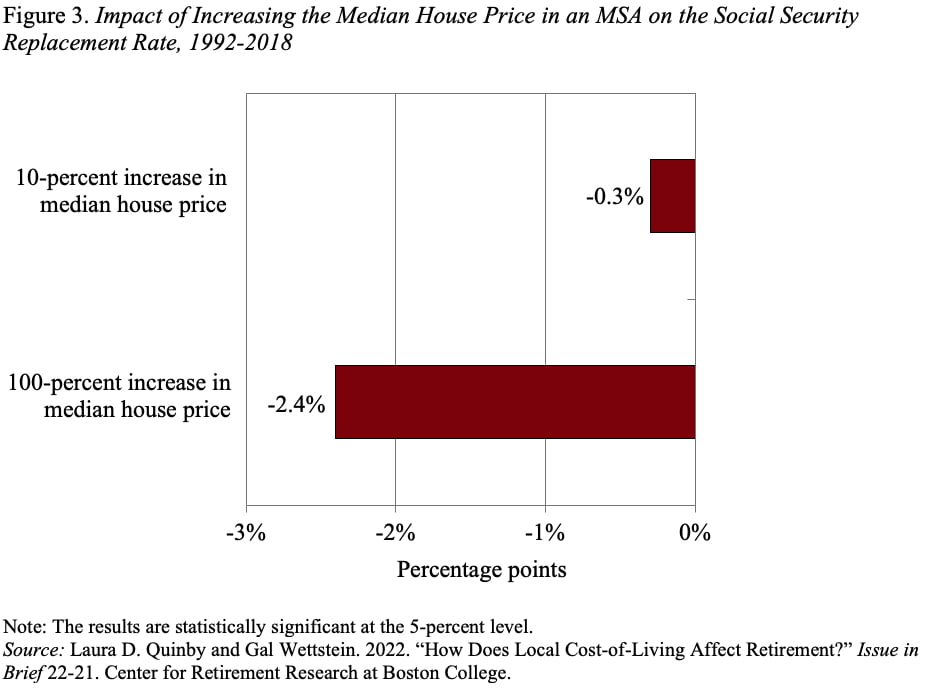

Given the small difference in earnings, it is not surprising that regression results show that even doubling the median house decreases the replacement rate by only 2.4 percentage points. Although this relationship is highly statistically significant, it is economically small given that the average replacement rate in the lowest-cost MSAs is 53 percent (see Figure 3).

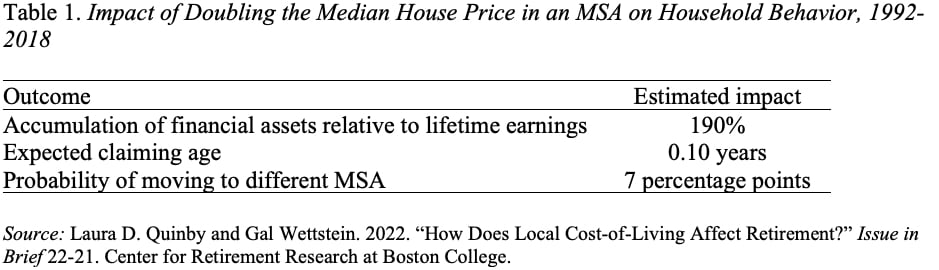

The analysis then turns to behavioral impacts. Table 1 presents regression estimates for the three outcomes of interest.

- On the saving front, doubling the median house price in a household’s MSA is associated with increased financial assets worth nearly two times lifetime average annual earnings. This amount of new saving virtually eliminates the replacement-rate gap.

- Turning to the claiming age, the impact of the median house price is positive – indicating that workers retire later when they live in high-cost areas, all else equal – but it is small in magnitude and statistically insignificant.

- Finally, with respect to decisions about relocating, households living in high-cost areas are more likely to move across MSAs, but the regression estimate is only weakly significant.

In short, variations in Social Security replacement rates across the country do not appear to be that big of a deal. Yes, they are lower in high-cost areas, but the gap is small. And households appear to respond primarily by saving more.