A Major Factor Behind the Drop in Disability Rolls Is “Retraining” of Judges

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Have we become more concerned about limiting participation than protecting the vulnerable?

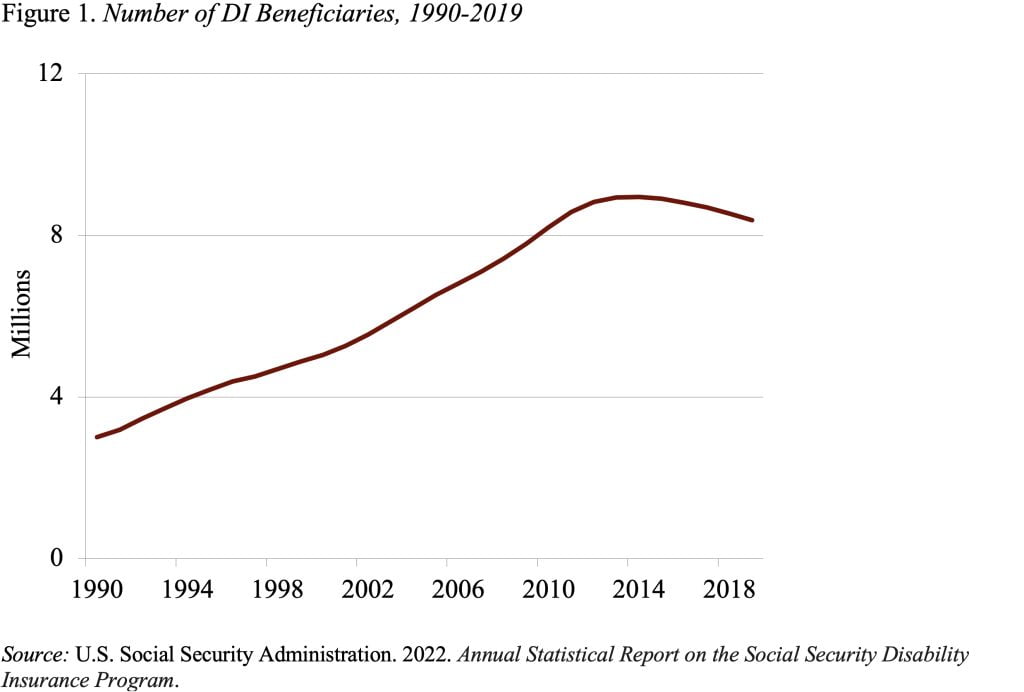

In 2015, the number of individuals receiving Social Security Disability Insurance (DI) benefits began to drop, reversing an upward trend that had persisted for two decades (see Figure 1). My colleagues explored why.

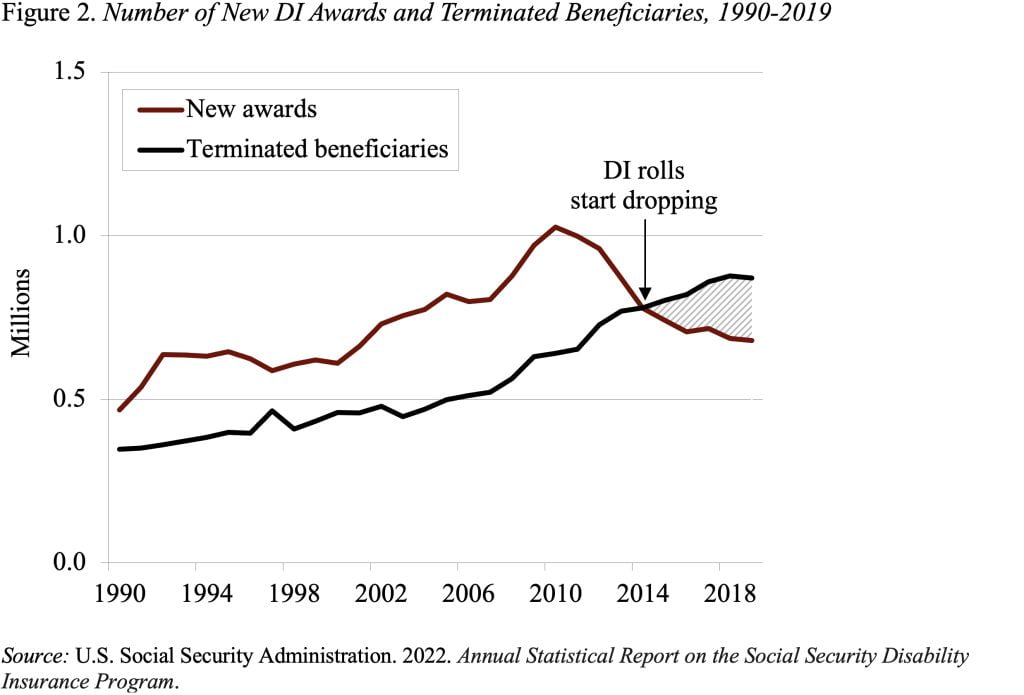

They started by looking at whether the drop is due to more people leaving or fewer people coming on the rolls. In fact, the number of people leaving the rolls – aging into Social Security’s retirement program – has been increasing steadily for decades (see Figure 2). But the number of new DI awards was also increasing, so more people were coming on than going off. Then in 2010 new DI awards started to drop, and by 2015 new awards finally fell below terminations so the DI rolls began to drop.

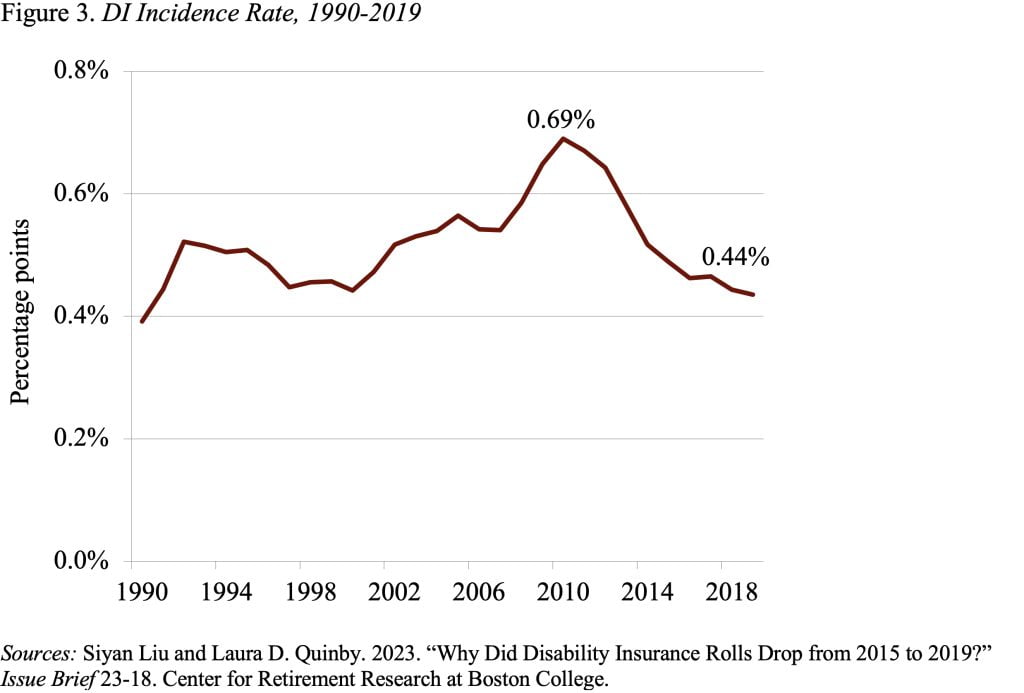

So, the real question is why the DI incidence rate – new awards as a percentage of covered workers – dropped (see Figure 3). Three factors could be playing a role:

- Population aging may have reduced the number of DI applications as workers instead claimed their retirement benefits.

- A strong economy following the Great Recession made DI less attractive to prospective applicants with some ability to work.

- Policy changes at the Social Security Administration – notably, field office closures and retraining of Administrative Law Judges (ALJs) to reduce the rate of benefits awarded on appeal – increased the difficulty of applying and reduced the share of applicants who were accepted.

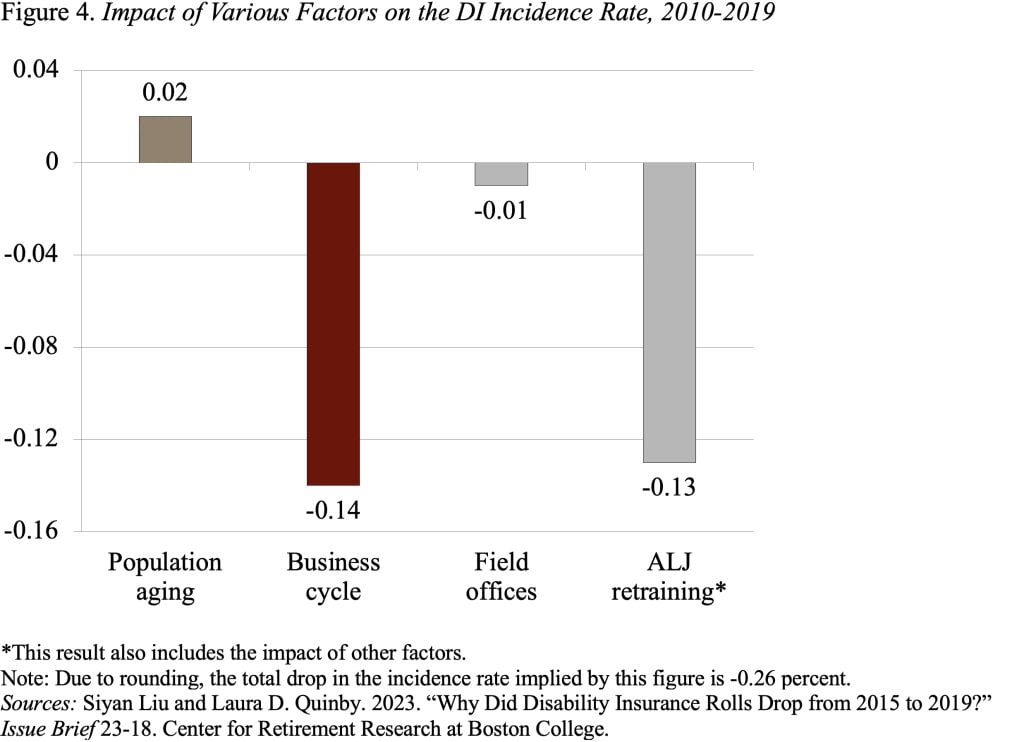

To sort out the relative importance of each factor, the authors multiplied the level change in each factor of interest (such as the unemployment rate or number of field offices) by its impact on awards. Specifically, for population aging, they calculated age-specific incidence rates to construct a counterfactual incidence rate if all the factors, except aging, had remained at their 2010 levels. For the impact of a strong economy, they used regression analysis based on state data over time to estimate how a 1-percentage-point change in the unemployment rate affects the DI application rate. For policy changes, they took estimates from the academic literature for the impact of closing field offices and assumed that any remaining difference between the actual incidence rate and the counterfactual incidence rate was the effect of ALJ retraining.

Figure 4 shows how much of the 0.25-percentage-point drop in the incidence rate is attributable to each factor. The gold bar shows that, between 2010 and 2019, population aging would have increased the incidence rate by 0.02 percentage points if all the other factors had stayed constant. The red bar shows the impact of the business cycle, which decreased the incidence rate by 0.14 percentage points. The first gray bar incorporates field office closures, decreasing the rate by a slight 0.01 percentage points. Lastly, ALJ retraining is estimated to have reduced the incidence rate by 0.13 percentage points. Ultimately, the business cycle and a stricter process for awarding benefits on appeal emerge as the two most important factors driving down the incidence rate in recent years.

These findings do raise the question whether, with the finances of DI now on a strong trajectory, the time may have come to rebalance the goals of DI away from protecting the program and more to protecting vulnerable people.