Can Employer Demand Support Older Workers Today…And Tomorrow?

The brief’s key findings are:

- Many older workers are inclined to work longer, but will employers hire and retain them – today and in the future?

- A series of CRR studies on this topic provide a case for tempered optimism.

- First, hard data suggest that older workers are at least as productive as younger ones, though they do cost more.

- Second, survey data show that employers’ views are largely in line with these hard data, and job postings confirm a willingness to hire.

- Finally, while the jobs that older workers do today may be less prevalent in the future, jobs that they have the skills for should be available.

Introduction

A common refrain among retirement researchers is that longer careers are the best way to ensure an adequate retirement. This refrain is often directed at the workers themselves – “you need to work longer!” And that message seems to have been getting through. Since the 1990s, the labor force participation rates of older individuals have increased. But, workers are just one side of the market: the supply side. Their ability to work longer also depends on whether employers are willing to hire and retain them. The question is, what does employer demand for older workers look like today and in the future?

To answer the question, this brief synthesizes the results of several recent Center studies. These studies examine employer demand from three different angles: 1) the reality of older workers’ value today; 2) employers’ perceptions of that productivity; and 3) whether older workers’ skills will be a good fit for the jobs of the future.

The discussion proceeds as follows. The first section focuses on how today’s workers affect the bottom line in terms of productivity and profitability. The second section considers how employers perceive the value of older workers using two measures: what employers say to a survey-taker and what they do with respect to postings on a job board. The third section looks ahead to assess how well older workers’ abilities match projections of employer demand in 2030.

Overall, room for tempered optimism exists. First, older workers may be just as good as younger workers for a firm’s bottom line. Second, employer perceptions appear mixed – they say older workers are at least as productive but relatively expensive, which may explain why their job listings specifically targeting older workers are mainly for lower paying positions with limited benefits. Third, while the jobs older workers do today may be less prevalent in the future, other jobs that older workers have the capacity to do should be plentiful.

Are Today’s Older Workers Good for Business?

In assessing labor demand for any group, the hope is that workers’ contributions to firm profitability are the primary consideration. But, while measuring these contributions may sound straightforward, it is not. The major challenge is the availability of data that contain both information on workers’ characteristics – like age – and objective measures of employer profitability.

Fortunately, Center researchers obtained access to restricted Census data and were able to combine three databases: 1) the Longitudinal Employer-Household Dynamics; 2) the Longitudinal Business Database; and 3) the Census’ Business Register.1Quinby, Wettstein, and Giles (2023). These datasets contain information on employee characteristics and earnings, payroll and revenue, and location and industry. So, the data allow researchers to track businesses and establishments over time, while observing their revenues, payroll, and the age composition of their workforces.

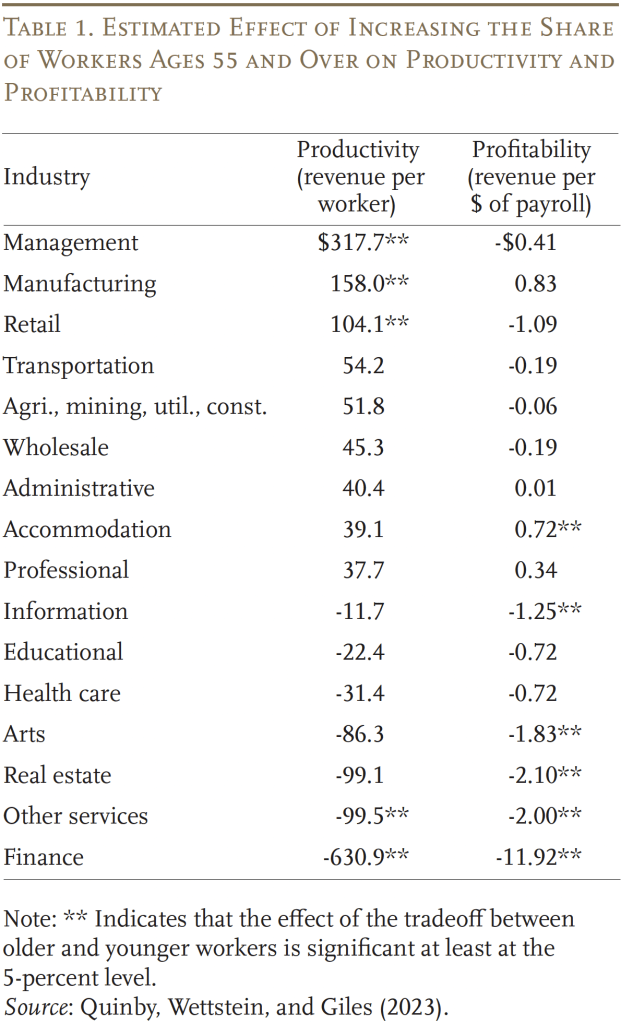

With these data in hand, the study estimated how two measures of firm performance would change if younger workers were replaced by older ones. The first measure was worker productivity, defined as revenue divided by the number of employees. The second measure was profitability, defined as revenue per dollar of payroll. The effect of exchanging younger workers for older ones was estimated using regression analysis to compare firms with workforces that are otherwise similar in racial, ethnic, and educational makeups, as well as geographic location. This estimation was done in two ways: 1) across many industries in a manner that yielded non-causal (i.e., correlational) results; and 2) in manufacturing only, exploiting special features of this industry to obtain causal results.

Table 1 shows the correlational results. On the productivity side, no clear evidence supports the notion that older workers are less productive. Three of the five significant results are positive, with management, manufacturing, and retail all showing productivity gains from older workers. Just two industries – in particular finance – show a significant reduction in productivity. The other results are not significantly different from zero.

On profitability, the picture is more lopsided, with the estimates generally indicating that a larger share of older workers is associated with lower profits, which is consistent with a large body of research showing that wage growth for older workers continues even after their productivity flattens out. Still, in the majority of industries the results were not significantly different from zero, indicating no clear difference in profitability between older and younger workers. And, the more sophisticated estimation method – which sought to obtain causal results – found no evidence of lower profitability in manufacturing for firms with older workforces.

So, while estimates vary by industry, the evidence suggests that older workers are at least as productive as younger ones. And, while older workers’ higher costs may eat into profitability in some industries, in most cases older and younger workers are indistinguishable on this front. Indeed, the highest-quality evidence, relevant to the limited but important manufacturing industry, finds no evidence of reduced profitability from older workers. However, if these findings are to be reflected in actual demand for older workers, then employers must have a perception that matches this reality.

How Do Today’s Employers Perceive Older Workers?

To understand current employer perceptions of older workers, the Center used two approaches. The first was to simply ask employers through a survey. The second was to explore what employers actually do by analyzing job postings.

What Do Today’s Employers Say about Older Workers?

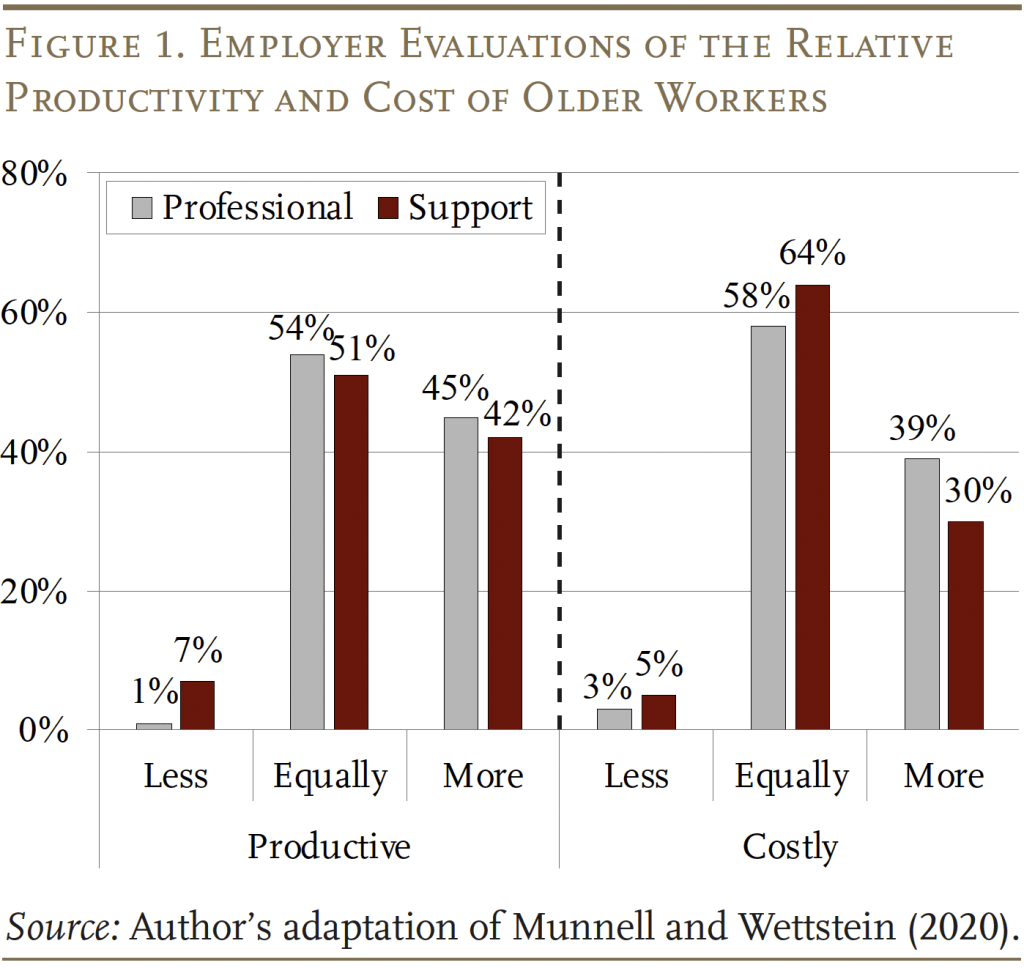

In 2019 – before the pandemic – the Center commissioned a telephone survey by Greenwald and Associates.2Munnell and Wettstein (2020). The survey queried employers on their views of workers’ productivity and costs – two issues that came up in the study above. Figure 1 shows how employers viewed the productivity and costs of workers ages 55 and over versus those under 55, separately for professional and support staff.

The results indicated that employers’ stated views of older workers’ relative productivity and costs are roughly consistent with the objective measures of workers’ value discussed earlier. On the productivity front, very few employers view older workers as less productive. The majority say that older workers are equally productive, with a large fraction seeing them as more productive. On the cost side, the news is less positive. While the majority of employers see older workers as equally costly, a sizable minority see them as more costly than younger ones.3It is worth noting that the 2019 survey was meant to replicate an earlier study, conducted in 2006. The 2019 results are more favorable to older workers – specifically older support/production workers – than the 2006 edition. See Munnell, Sass, and Soto (2006).

OK, so the majority of today’s employers say that older workers are at least as productive as younger ones, and many also view them as no costlier. But, do employers act this way, recruiting older workers for opportunities on par with younger ones?

Do Today’s Employers Seek Out Older Workers?

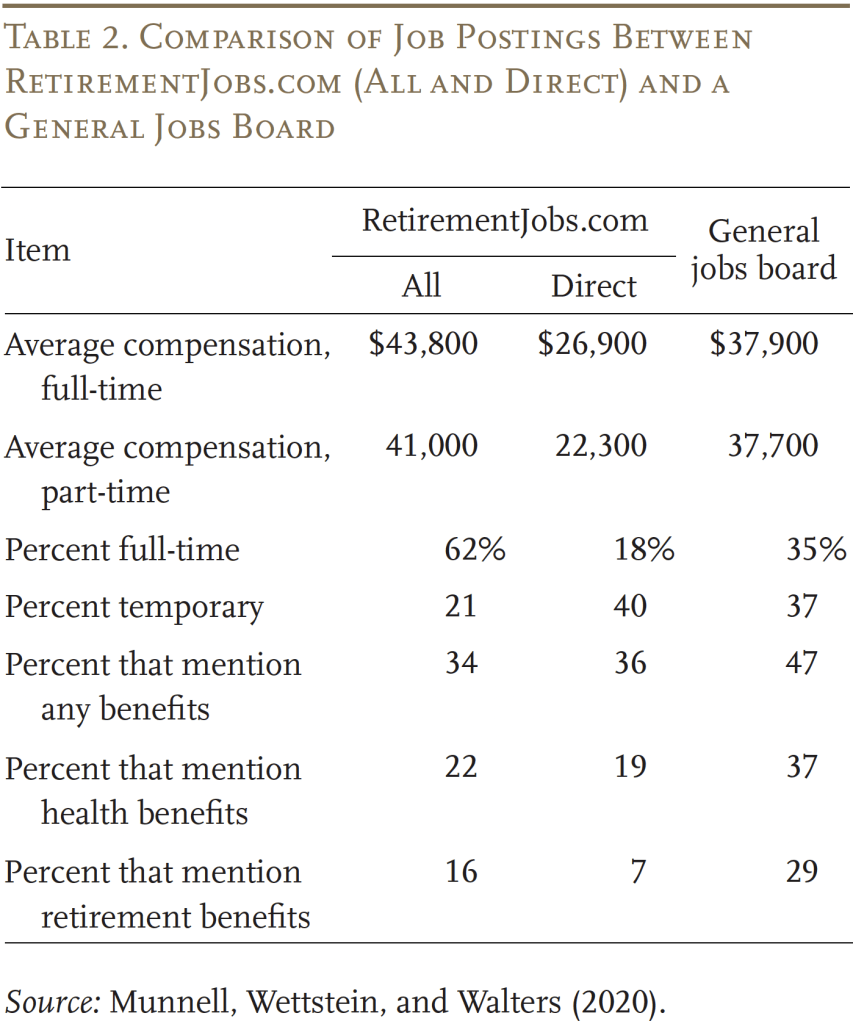

To explore whether employers actively recruit older workers, the researchers turned to RetirementJobs.com, the only major job posting site targeted to individuals ages 50 and over. Specifically, the Center researchers were given access to the website’s postings as of November 2019, which captures the picture before the disruptions of the pandemic era.4For each listing, RetirementJobs.com provided the employer’s name, region of operation, job title, and whether the job was full- or part-time. These structured fields were supplemented by the job descriptions, which were manually coded to identify information on salary and benefits. For more detail, see Munnell, Wettstein, and Walters (2020). Although RetirementJobs.com is considerably smaller than Monster.com or Indeed.com, it is the only one of these websites that can provide data on jobs targeted to older workers.

The analysis divided the jobs on the website into two types. First, it used openings directly posted to RetirementJobs.com, which represented 20 percent of all listings. These “direct” postings capture employers aiming explicitly at older workers. The second type of postings are those fed to the site from CareerBuilder.com. These “indirect” postings suggest employer willingness to hire older, as well as younger, workers. Any difference between direct versus indirect postings would provide some insight into the types of jobs that target older workers specifically as compared to those that are not intended solely for a specific age range.

Center researchers next turned to a comparison between RetirementJobs.com and one of the largest general job boards in the country. Since this general job board contains millions of listings, a random sample of 15 listings from each state was selected for a total of 765 listings.5Because the total number of listings varies by state, the sample for each state was weighted to reflect its total underlying listings. The analysis compares these jobs to both all jobs posted on RetirementJobs.com and the jobs directly targeted at older workers.

When focusing on all jobs posted on RetirementJobs.com, the results contain some positive news for older job seekers, with an important caveat (see Table 2). The first positive point is that the salaries for both the part- and full-time jobs on RetirementJobs.com are significantly higher than those on the general jobs board. Another piece of good news is that the jobs are more likely to be full-time positions. The main caveat is that these jobs seem less likely to mention either health or retirement benefits. So, older workers may have good opportunities for bridge jobs to retirement, but fewer chances to obtain the full benefits often associated with “career” jobs.

When restricting to jobs posted directly to RetirementJobs.com, however, the positive takeaway of higher salaries does not hold. The direct postings offer significantly lower wages than the general jobs board. And, directly posted jobs have less full-time work, more temporary work, and fewer benefits. So, the job postings most specifically targeting older workers seem to be of lower quality than the postings that are not age specific, either those appearing on RetirementJobs.com or the general jobs board.

Summing Up Demand for Older Workers Today

Based on the findings of the three Center studies discussed above, the situation seems relatively positive for older workers today. In most industries, they are at least as productive as younger ones. And, while their higher wages eat into profitability, in many industries older and younger workers are indistinguishable with respect to this metric. In a survey, today’s employers indicate that they recognize these objective measures, viewing older workers to be at least as productive as younger ones, albeit sometimes with higher costs. And, to an extent, employers appear to act this way. They post relatively high-salary jobs to a website targeting older workers, although jobs that most directly aim for these workers pay less and have fewer benefits. All-in-all, things seem OK today. But, what about tomorrow?

Will Demand for Older Workers Hold up Tomorrow?

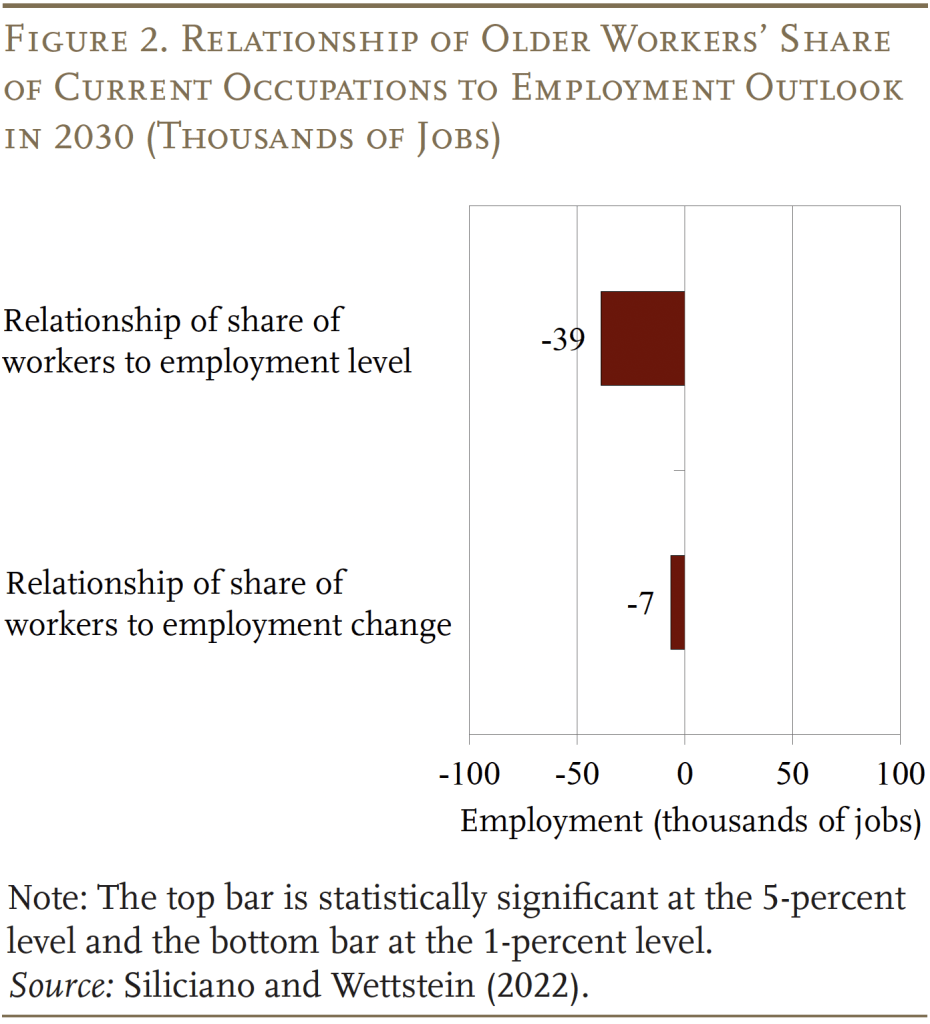

To assess whether older workers are likely to have good access to jobs in 2030, Center researchers tried two different approaches.6Siliciano and Wettstein (2022). The first one was simply to look at the jobs older workers are doing today and compare them to Bureau of Labor Statistics’ projections on the level of those jobs in 2030. This analysis answers the question: are older workers currently doing jobs that are expected to be plentiful at the end of the decade?

The second approach addressed a slightly different question: are older workers able to do the jobs that will be plentiful in 2030, even if they are not doing them now? This approach required the creation of a “Suitability Index” that measured how well older workers are likely to do certain jobs. The Index is composed of three indicators for each occupation: 1) the extent to which the skills needed erode with age; 2) the disability application rates; and 3) the average retirement age. The Index provides a convenient summary measure of which occupations are most congenial to older workers, which can then be compared to the growth rates of various occupations projected to be available in 2030.7For more details, see Siliciano and Wettstein (2022).

The first approach yields a discouraging result. Figure 2 shows that a one-percentage point increase in the share of older workers in an occupation today is associated with fewer jobs in 2030. This negative association exists whether the availability of future jobs is measured absolutely using the projected level in 2030, or as a rate of change between 2020 and 2030.

But what about jobs older workers can do, but may not currently be doing? Here, using the Suitability Index, the Center study found no statistically significant relationship – neither a positive one nor (importantly) a negative one – between the suitability of occupations for older workers and the projected number of jobs in occupations in 2030 or the growth from 2020-2030. This finding is somewhat encouraging, as it suggests that there may not be a mismatch between the jobs older workers are capable of doing and those available in the future. In other words, those jobs older workers can do are apparently not going away, even if the ones they are currently doing appear to be becoming less common.

Conclusion

For decades, researchers have been encouraging workers nearing retirement age to keep working. But this prescription won’t work unless employers are also interested in hiring and retaining these workers. On the employer-demand side, the overall picture from the Center’s research seems fairly encouraging. Today, the hard data suggest that older workers are at least as productive as younger ones and largely indistinguishable on profitability. Furthermore, employers’ stated perceptions on a survey are largely in line with these data. So are employer actions; while employers seem to target lower-paying jobs specifically at older workers, they also show a willingness to post high-paying jobs to RetirementJobs.com.

Finally, little reason exists to doubt that the future will look much different. While the specific jobs older workers do today may be less prevalent in the future, our analysis indicates that jobs in occupations that are suitable for older workers are likely to grow at a similar pace as other jobs. So, while older workers may need to change with the times and enter some new occupations, their skills should enable them to do so. Taken together, it seems that if older workers are willing to supply their labor then demand should likely be there, today and into the future.

References

Munnell, Alicia H. and Gal Wettstein. 2020. “Employer Perceptions of Older Workers – Surveys from 2019 and 2006.” Working Paper 2020-8. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Munnell, Alicia H., Gal Wettstein, and Abigail N. Walters. 2020. “What Jobs Do Employers Want Older Workers to Do?” Working Paper 2020-11. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Munnell, Alicia H., Steven A. Sass, and Mauricio Soto. 2006. “Employers Attitudes towards Older Workers: Survey Results.” Issue in Brief 6-3. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Quinby, Laura D., Gal Wettstein, and James Giles. 2023. “Are Older Workers Good for Business?” Working Paper 2023-19. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Siliciano, Robert L. and Gal Wettstein. 2022. “Will the Jobs of the Future Support an Older Workforce?” Working Paper 2022-2. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Endnotes

- 1Quinby, Wettstein, and Giles (2023).

- 2Munnell and Wettstein (2020).

- 3It is worth noting that the 2019 survey was meant to replicate an earlier study, conducted in 2006. The 2019 results are more favorable to older workers – specifically older support/production workers – than the 2006 edition. See Munnell, Sass, and Soto (2006).

- 4For each listing, RetirementJobs.com provided the employer’s name, region of operation, job title, and whether the job was full- or part-time. These structured fields were supplemented by the job descriptions, which were manually coded to identify information on salary and benefits. For more detail, see Munnell, Wettstein, and Walters (2020).

- 5Because the total number of listings varies by state, the sample for each state was weighted to reflect its total underlying listings.

- 6Siliciano and Wettstein (2022).

- 7For more details, see Siliciano and Wettstein (2022).