Can Incentives Increase the Writing of Wills?

The brief’s key findings are:

- Writing a will ensures a person’s wealth goes to intended recipients, preventing major assets like a house from being split up among many heirs.

- Yet many people do not have a will, particularly lower-income and non-White households.

- Using a survey experiment, the analysis explores whether customer interactions with banks could encourage will-writing.

- The results show that:

- combining will-writing with taking out a mortgage – a complex and stressful event – is a bad idea;

- offering people money helps, but mainly those who need it the least; and

- linking will-writing to a simpler task, like opening an account, is a much more effective option, especially for disadvantaged groups.

Introduction

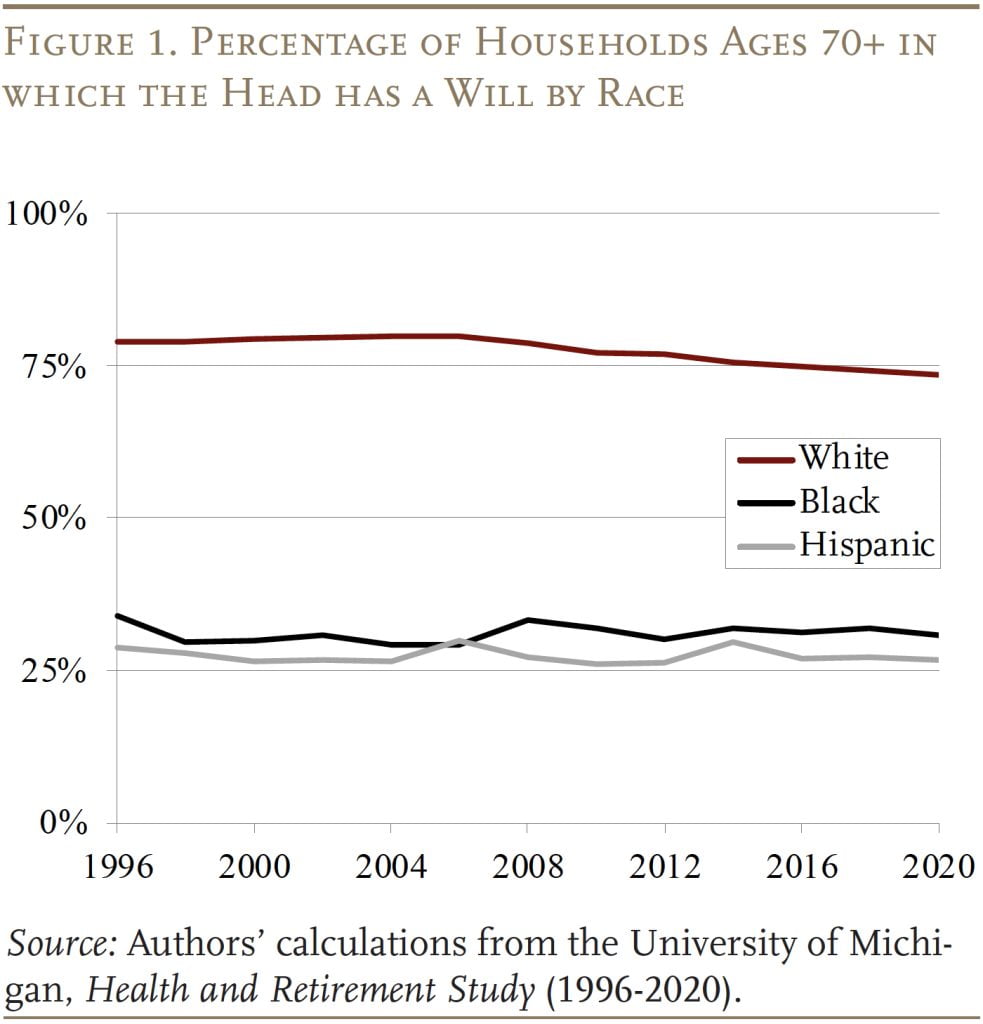

Writing a will can improve the transmission of wealth across generations by preventing the dissipation of assets – such as a family home divided among multiple heirs – and by encouraging donors to save for their beneficiaries. Despite the advantages of having a will, the percentage of households with a will is surprisingly low. For those ages 50+, less than half of household heads have a will. By age 70, that share increases to 67 percent, but the shares are much lower for less wealthy households and for Black and Hispanic households. The question is whether targeted bequests can be increased through an intervention that promotes will-writing.

To answer that question, this brief, which is based on a recent study, reports on the results of an online survey and experiment administered by NORC at the University of Chicago.1Aubry, Munnell, and Wettstein (2023a). The participants are asked a series of questions about whether or not they have a will and why. Those without a will then participate in an experiment where they are randomly assigned to one of four treatment groups to determine whether various incentives would encourage them to write a will.

The discussion proceeds as follows. The first section provides some background on the importance of wills and will status by race/ethnicity. The second section describes the survey. The third section presents the results regarding who has and does not have a will and why. The fourth section presents the results of the experiment, which show that setting matters – combining writing a will with taking out a mortgage is a bad idea; offering people money helps; and monetary incentives are more effective for those who are more financially sophisticated and for White respondents. The final section concludes that most people without a will intend to write one in the future and that incentives can affect this outcome. However, adding a will to an already stressful event such as taking out a mortgage has a negative effect on intentions.

The Importance of Wills

The difference between having some wealth and relying solely on current income is huge. Wealth provides a buffer that allows families to withstand emergencies or to cover expenditures in the face of unemployment. It enables people to take risks when selecting jobs – forgoing some compensation up front for more income later. It provides families with the resources for a down payment on a house in an area with good schools, thereby improving the prospects for their families. For low-and middle-income children, one of the main ways to acquire some wealth is through an inheritance. Parents can leave their home or modest financial assets to their children, who in turn are more likely to leave a bequest to their children. These bequests may be small, but they can be life-changing.

The most effective way to ensure that wealth transfers go to the intended recipients is for the donor to have a will. Without a will, assets can get dispersed among multiple heirs, which can be a particular problem for people whose major asset is their home. In this case, all the heirs must coordinate before maintaining or selling the property. In terms of targeting bequests to the desired beneficiaries, states have established default rules, which can achieve a reasonable outcome for many traditional families, but can produce the wrong outcome when the intended beneficiaries are not related by blood, marriage, or adoption or when assets are hard to divide (like a house, rather than financial assets).

Despite the advantages of having a will only about two-thirds of households with heads ages 70 and older had a will in 2020, and the share of White households with a will was more than twice that for Black and Hispanic households (see Figure 1). Our earlier study on wills also showed that a significant difference persists even after controlling for other demographic characteristics, health, wealth, education, and marital status.2Aubry, Munnell, Wettstein (2023b). One reason for this difference is that people who receive an inheritance are more likely to leave a bequest, and Black, Hispanic, and other non-White respondents are significantly less likely to report ever having received an inheritance than Whites, even after controlling for other demographics and education.

In short, many families would be better off if they had a will to transfer their assets to their targeted survivors, and a survey is needed to see whether interventions are possible to encourage more will-writing.

The Survey

The survey was conducted using the AmeriSpeak panel run by NORC at the University of Chicago. The panel is nationally representative, and participants were eligible for this study if they were ages 25 and older. The five-minute survey was conducted online in April 2023 and included 3,047 respondents. The panel contains demographic details, such as gender, race, education, and marital status. To supplement this baseline information, the survey also included questions about whether the respondent had children.

Next, the survey asked about the individual’s “will” status. Does the individual have a will? If yes, then at what age did they establish a will? What motivated them to write a will? What is the likely size of their estate? To whom will these assets be bequeathed? If the individual does not have a will, then why not? How much does the individual have in total assets? Does the individual intend to write a will?

The survey then turned to an experiment to test the effectiveness of different treatments to increase will-writing for those without a will. Respondents were randomly assigned to one of four groups. After each option, participants in the treatment groups were asked whether they would seize the opportunity to write a will.

Control Group: Do you intend to write a will?

Treatment Group 1: If the bank offered the opportunity to establish a will (with free legal and financial advice) at the time of signing for the mortgage, would you take up that offer?

Treatment Group 2: If the bank offered the opportunity to establish a will (with free legal and financial advice) at the time of signing for the mortgage and gave you a $500 incentive to do so, would you take up that offer?

Treatment Group 3: Imagine you are opening a checking, savings, or investment account at a bank. If the bank offered the opportunity to establish a will (with free legal and financial advice) when you opened the account, would you take up that offer?

The next section reports on the will status and reasons for that status, and then the following section summarizes the outcomes of the experiment.

Results from the Base Survey

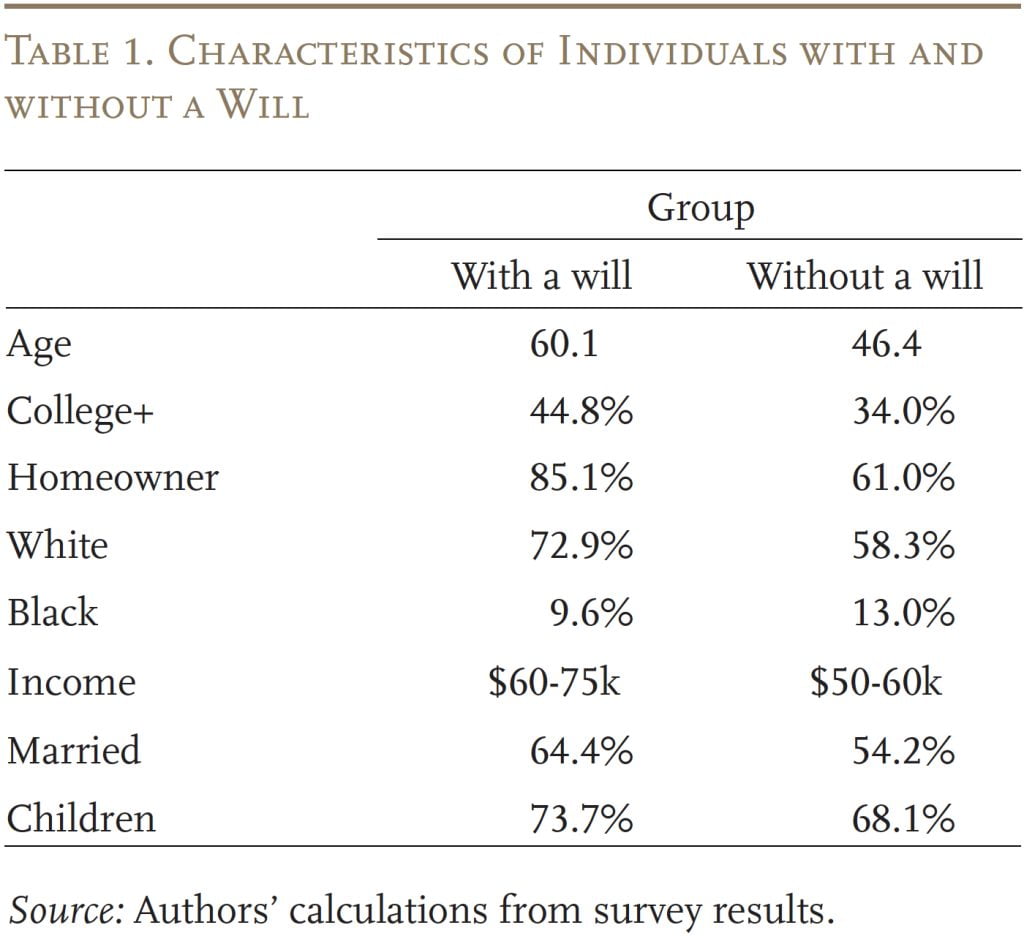

The survey showed that 34 percent of respondents had a will. These individuals were older, with more education, more likely to own a home, more likely to be White, and had somewhat higher income (see Table 1).

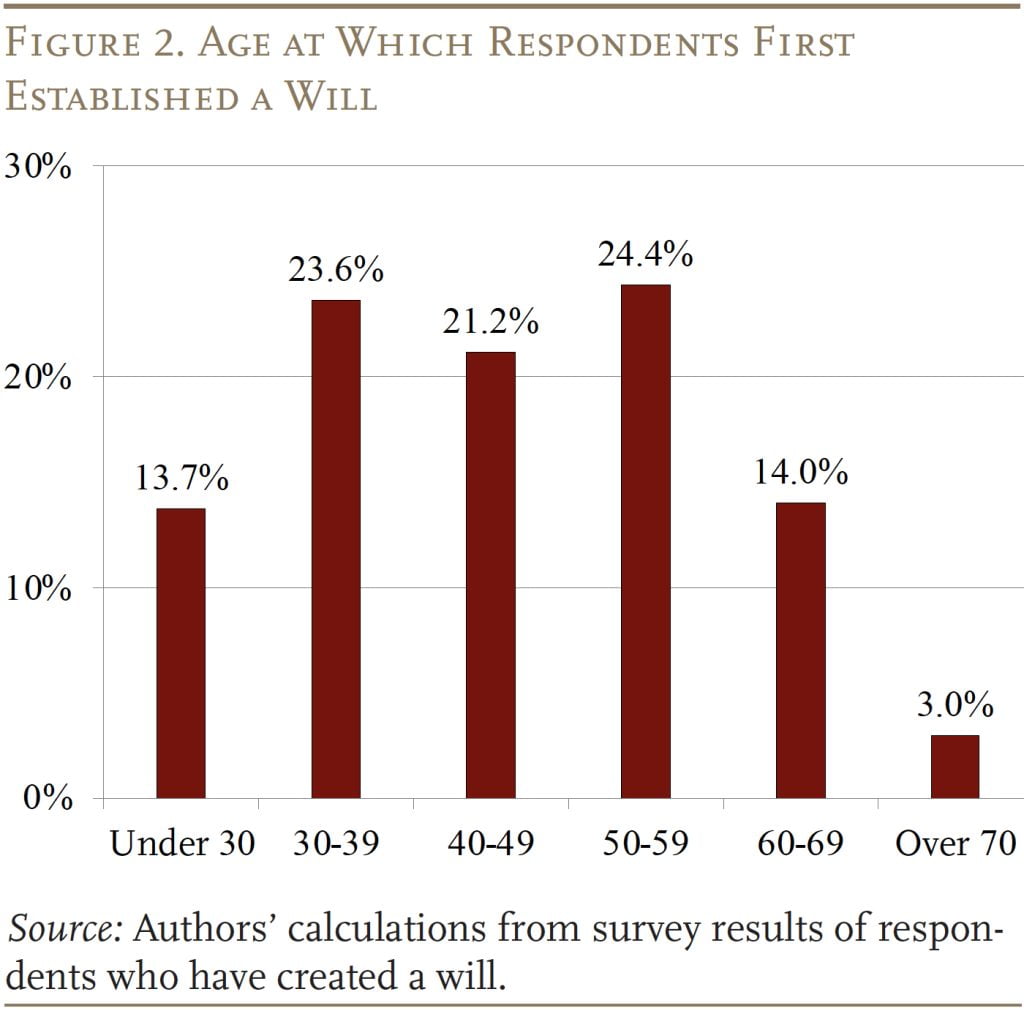

Most individuals set up their wills in their 30s, 40s, or 50s (see Figure 2).

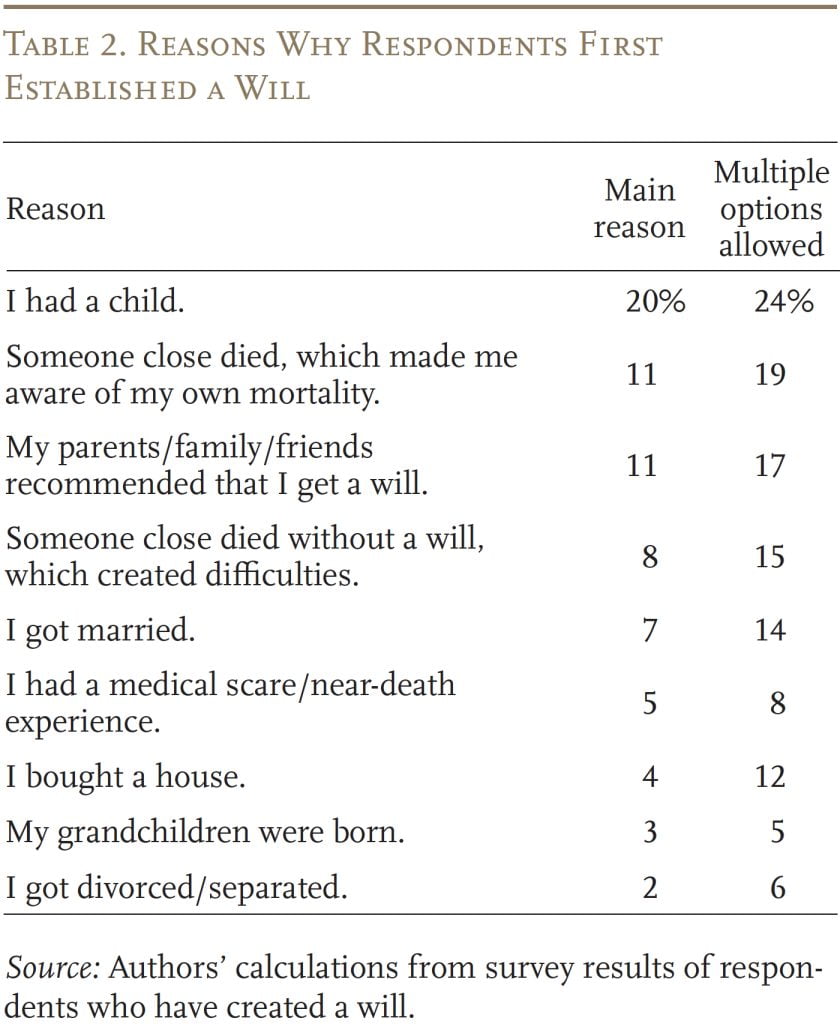

The most important motivating life event for writing a will was having a child (see Table 2). The next two reasons were more external: 1) someone close to the individual died, highlighting their own mortality; and 2) parents/family/friend recommended the individual establish a will.

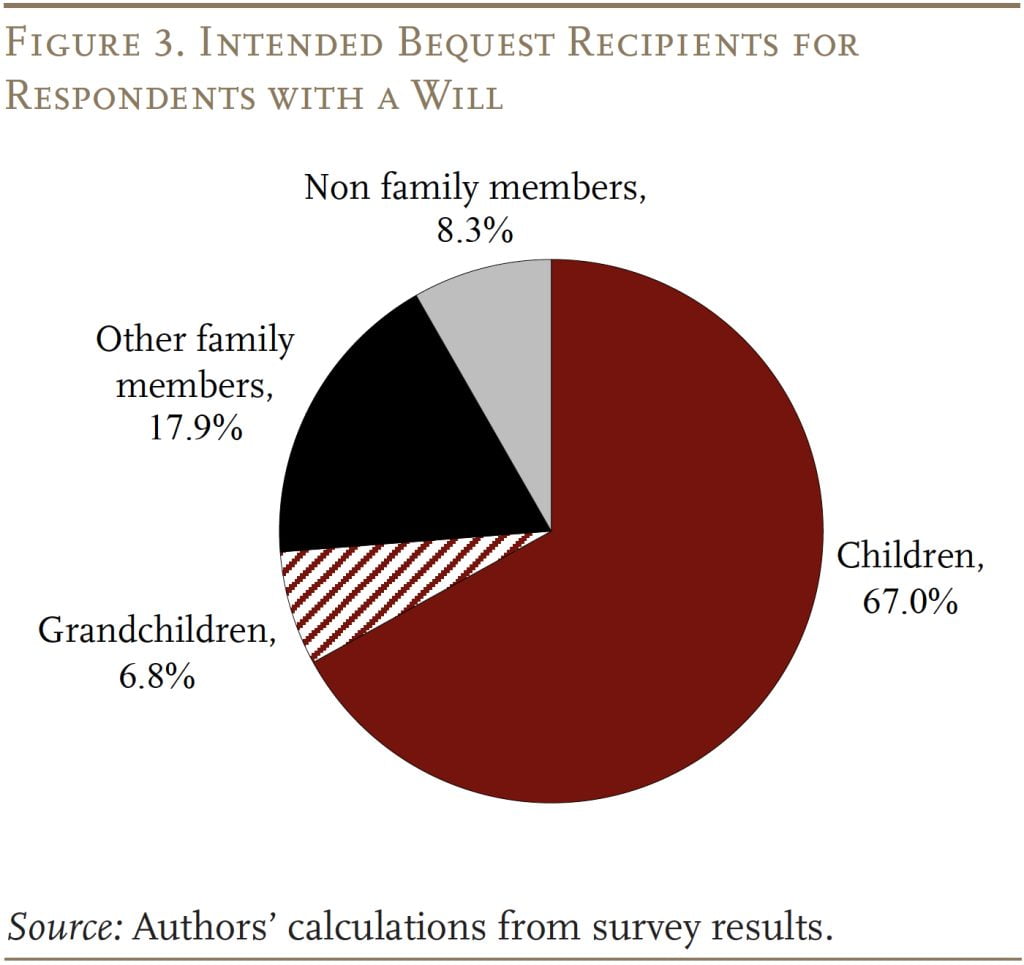

The survey also asks about intended recipients of a will. The results show that children account for two-thirds of the total and grandchildren 7 percent. Other family members account for 18 percent and non-family – both unrelated individuals and religious or charitable organizations – 8 percent (see Figure 3).

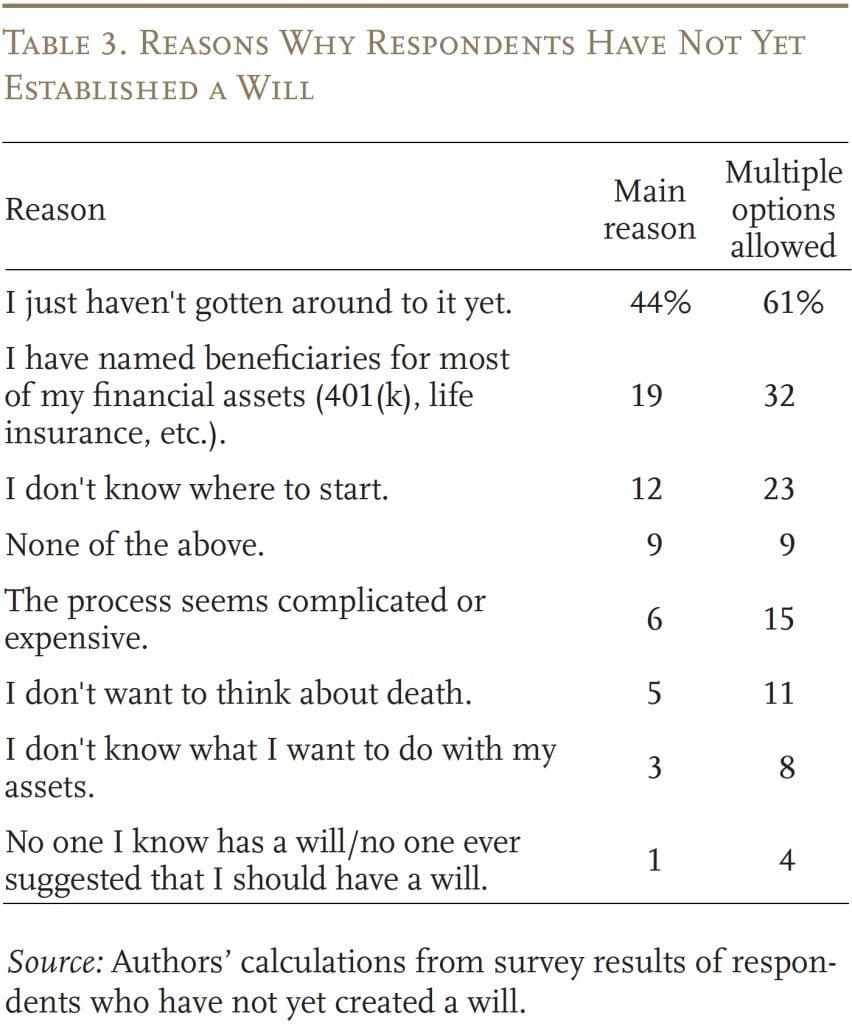

The remaining 66 percent of people did not have a will. The major reason offered for not having a will was: “I just haven’t got around to it yet,” (see Table 3). This response is consistent with earlier studies showing procrastination is a major problem when it comes to will-writing.3Fellows, Simon, and Rau (1978) and Contemporary Studies Project (1978). The second major reason is that some may have thought they had taken care of bequests, responding: “I have named beneficiaries for most of my financial assets (401(k), life insurance, etc.)” Many of the other responses suggested that people were generally baffled by the process.

Results from the Experiment

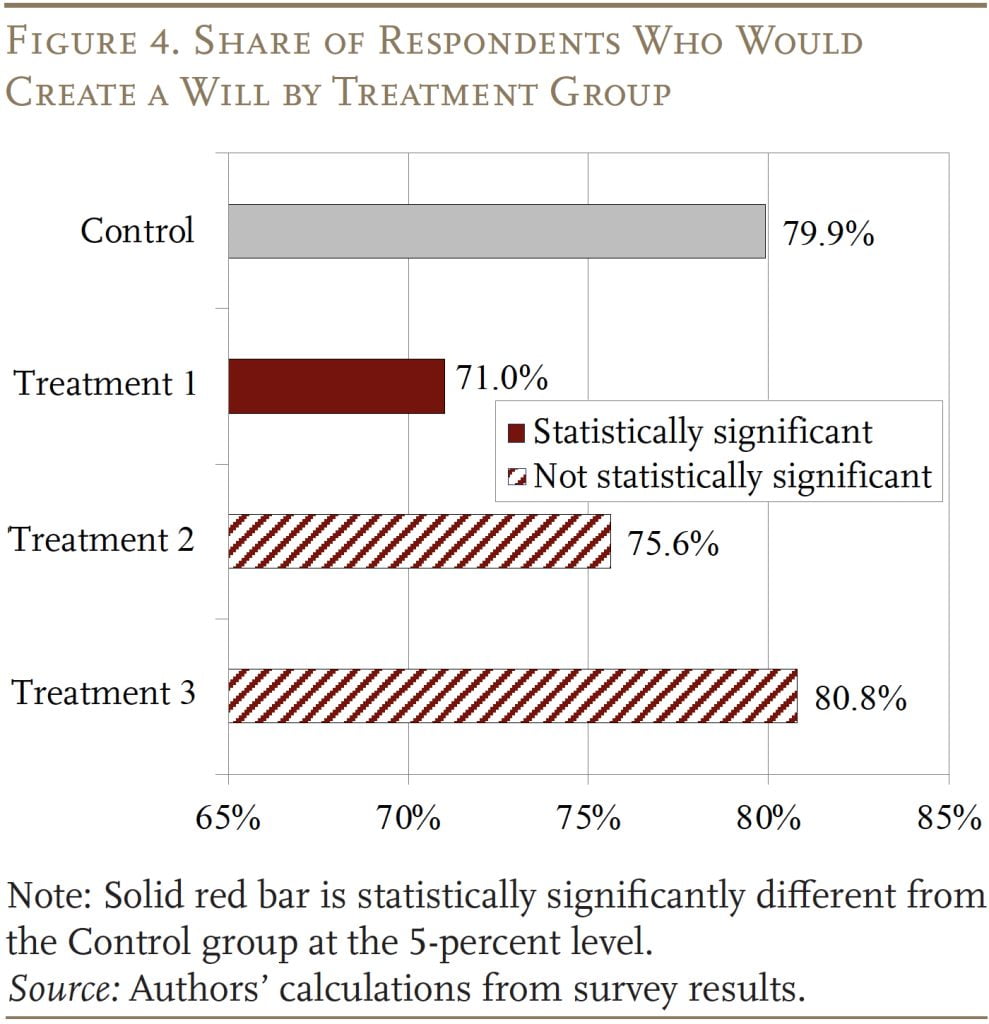

In terms of the impact of the experimental treatment on the intention to write wills, the results were unexpected – and at first disappointing – but, on reflection, do provide some real information. The disappointing news is that the first two treatments, which associated will-writing with the taking out of a mortgage, actually reduced the percentage of respondents who said they intended to write a will (albeit only statistically significantly for Treatment 1, see Figure 4). Without any treatment, 79.9 percent reported they intended to write a will; once the question was linked to the mortgage process, the percentage dropped to 71.0 percent – even with the offer of “free legal and financial advice.” Adding $500 to the proposal only brought the percentage halfway back to the no-treatment level. When the scenario changed from a mortgage environment to simply opening a bank account, the percentage intending to write a will increased to 80.8 percent.

One issue with the above results is that the only statistically significant coefficient is associated with Treatment 1, which links writing a will with taking out a mortgage. Neither Treatment 2 – offering $500 – nor Treatment 3 – providing a more pleasing bank interaction such as opening an account – produce statistically significant impacts. One possible explanation may be that the Control group is not quite consistent with the treatments in that it does not have a time element. Participants in the Control group are just asked if they intend to write a will, with no specific time frame. In contrast, all three treatment groups are asked: “Would you take up that offer?” That is, they are asked whether they would act at that moment.

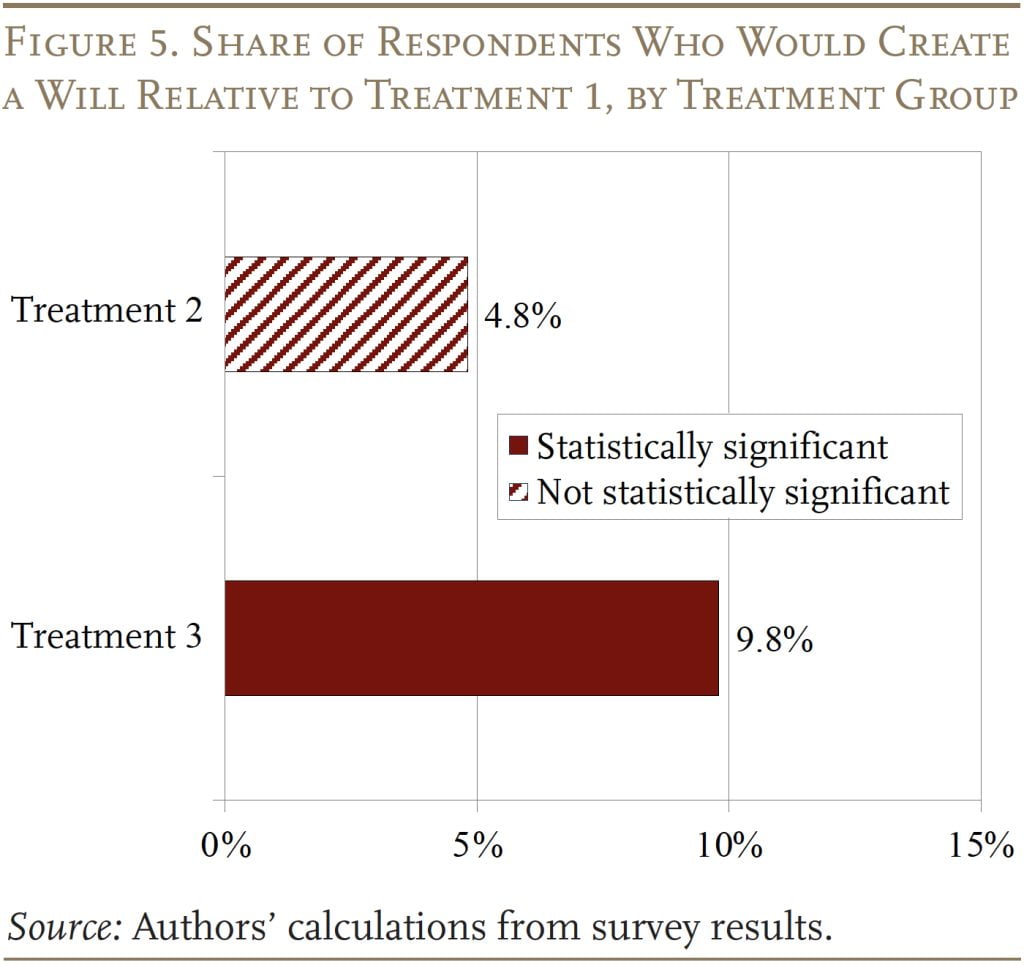

One way to circumvent the timing inconsistency to gain more information about the relative appeal of the three options is to drop the Control group and simply compare the treatment groups among themselves. The results of this exercise are shown in Figure 5. Here, offering $500 has barely any effect, but – even without the financial incentive – simply changing the base event from taking out a mortgage to opening an account – Treatment 3 – increases the share intending to write a will by 9.8 percentage points.

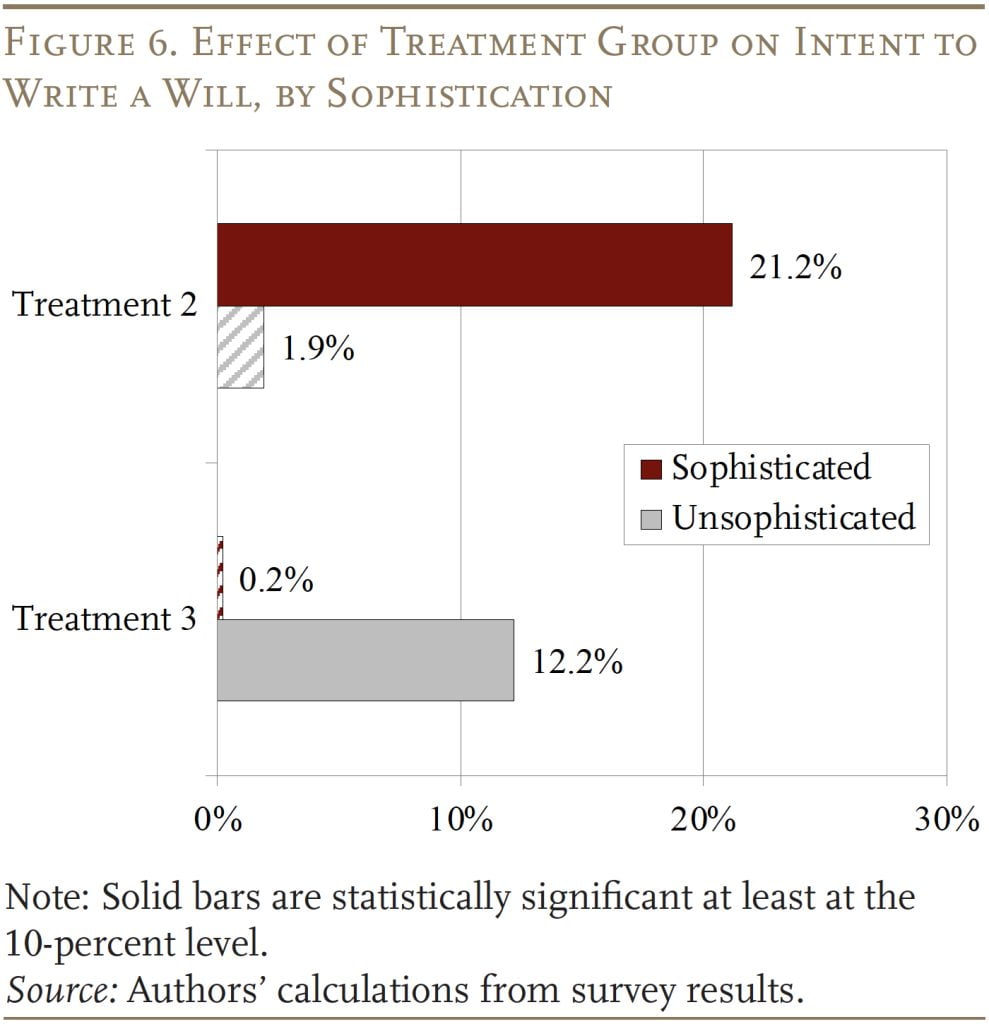

This formulation of the experiment can also be used to compare the impact of the treatments by individual characteristics. The first exercise attempts to separate the respondents by their sophistication, based on their responses to questions about why they do not have a will. This process, which is more art than science, included as “sophisticated” those who reported that their primary reason for not having a will was that they had named beneficiaries for most of their financial assets. The unsophisticated were those who offered any of the other responses.

The results by sophistication, in Figure 6, show that offering a $500 payment for writing a will (Treatment 2) increases the share intending to write a will by a huge 21 percentage points for the sophisticated, but by only a statistically insignificant 1.9 percentage points for the unsophisticated. In contrast, Treatment 3 (changing the setting) has a statistically significant effect on the unsophisticated – who are likely overwhelmed by the mortgage process – but not on the sophisticated.4It is helpful to clarify what the results of these group regressions show and do not show. The coefficients indicate the extent to which participants in each group are more or less likely to write a will under Treatment 2 (+ $500) or Treatment 3 (“opening account” instead of “taking out a mortgage”) relative to Treatment 1. What they do not show readily is whether the responses of the two groups differ in a statistically significant way. It is possible to glean some information by looking at the magnitude of the difference of the coefficients of the two groups relative to standard errors, but the only formal way to determine a statistically significant difference is by estimating equations with interactive terms. Such equations are included in Aubry, Munnell, and Wettstein (2023a).

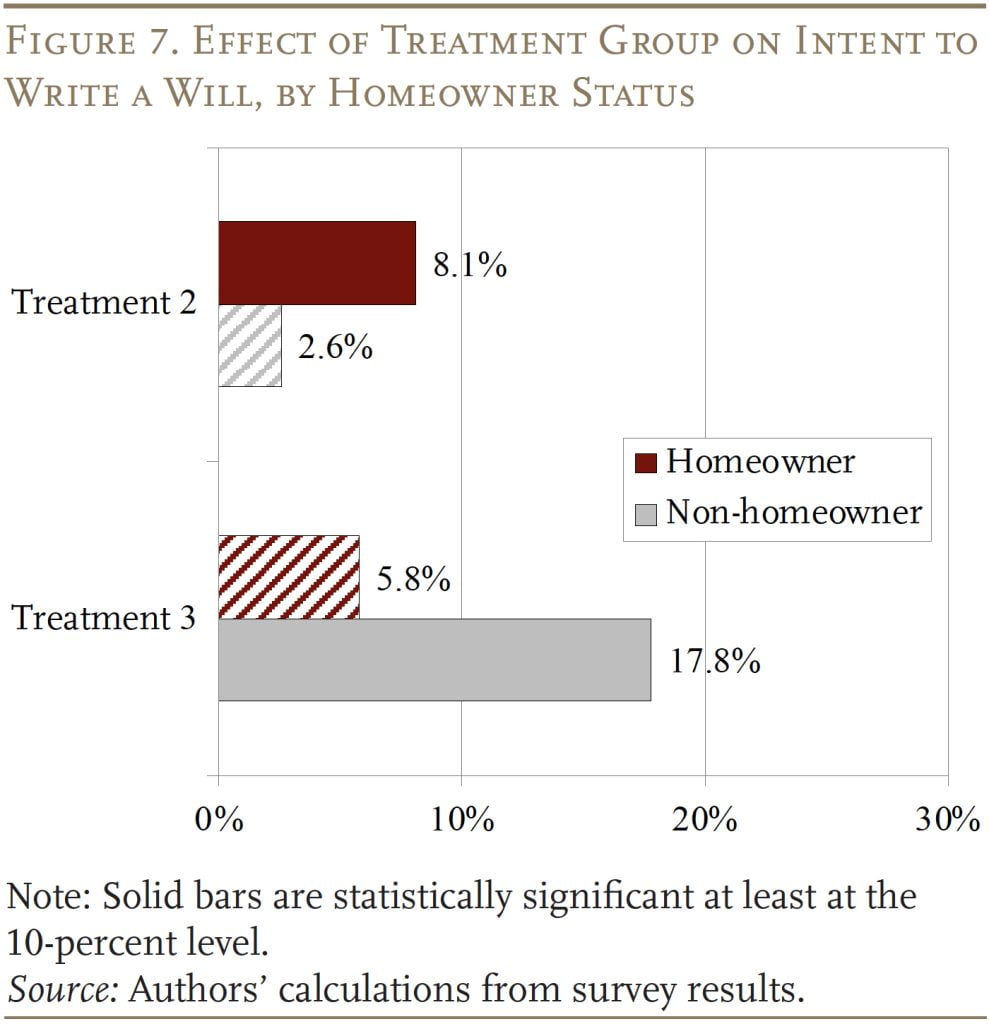

Another attempt to get at sophistication involves repeating the exercise for homeowners versus non-homeowners (see Figure 7). Adding $500 to the offer (Treatment 2) has a marginally statistically significant impact relative to Treatment 1 for homeowners, but not for non-homeowners. In contrast, changing the setting (Treatment 3) incents more will-writing for non-homeowners, while homeowners are much less sensitive to the setting. Homeowners could be less intimidated by the mortgage process because of prior experience or because a refinance mortgage is inherently less onerous than an initial mortgage.

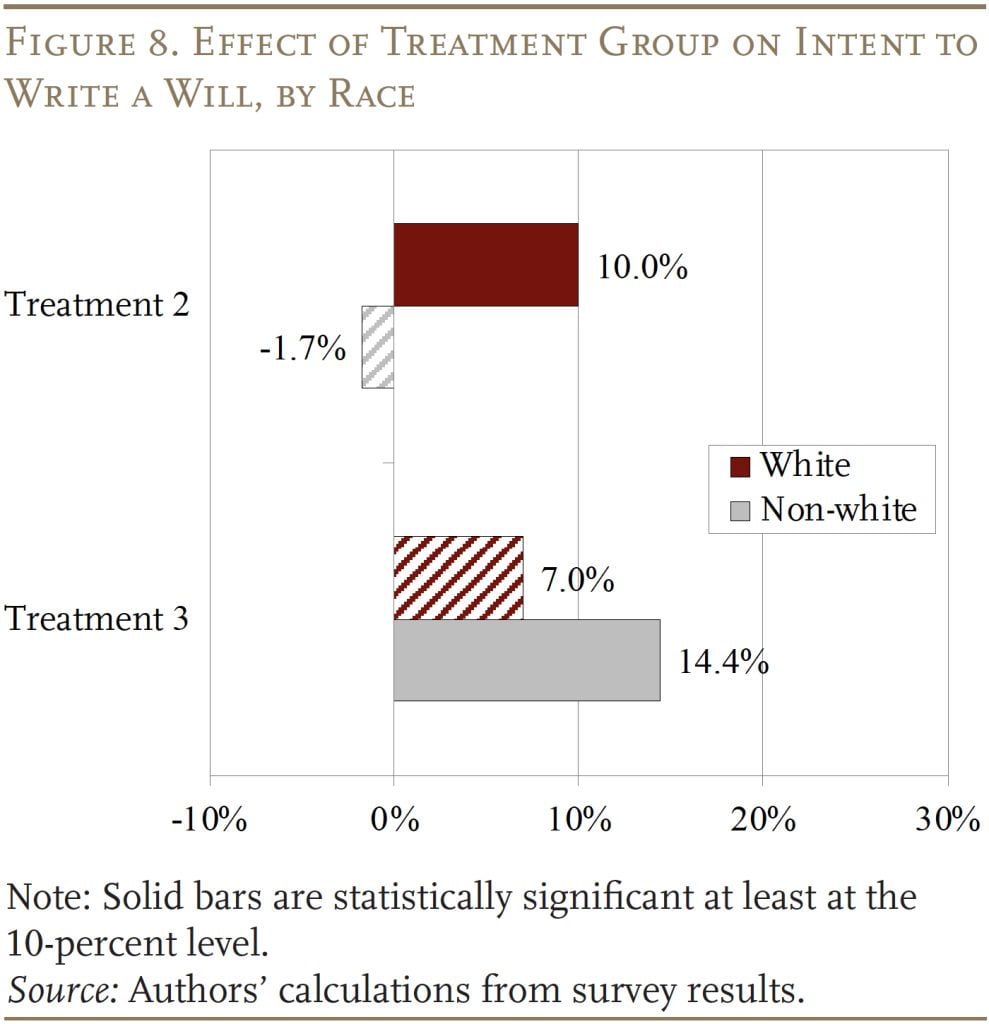

The final groupings involve race and gender. The results show that introducing the $500 incentive (Treatment 2) has a statistically significant effect on Whites, but non-White individuals do not respond (see Figure 8). In contrast, Treatment 3 has a statistically significant effect only for Non-Whites, indicating that they appear to have a really strong preference for moving the setting from taking out a mortgage to opening a bank account.

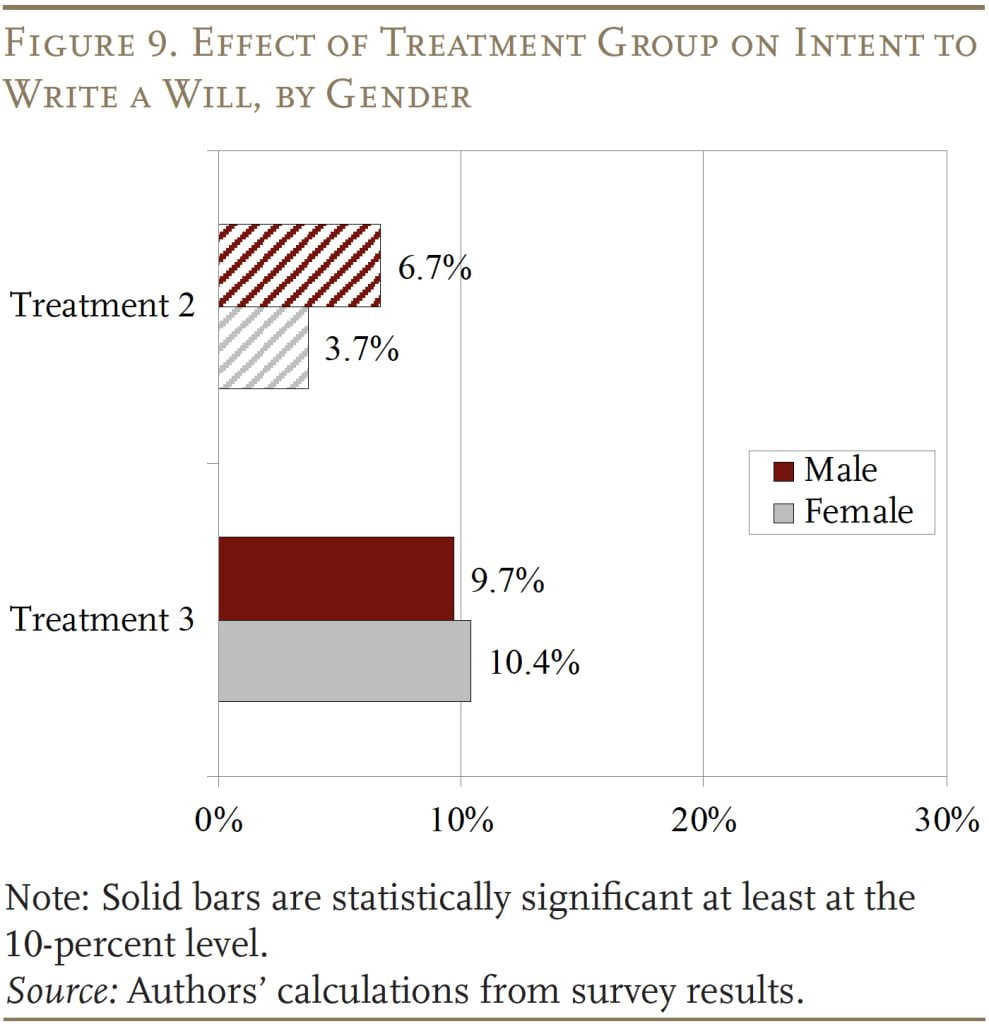

In terms of gender, both genders appear equally impacted by Treatments 2 and 3 (see Figure 9). Neither are affected by the $500 financial incentive, but both male and females would be more inclined to write a will in a less pressured setting.

The bottom line from these results is threefold. Most importantly, the setting matters. Trying to combine a somewhat complicated and emotional task such as writing a will with a complicated and exhausting process like taking out a mortgage does not work. Initially, it seemed like a good idea since the mortgage event involved focusing on many people’s largest asset – their home – and peripherally on their other finances. One might think that people taking care of a mortgage and a will at the same time could benefit from economies of scale in assessing their financial status. But any economies appear to be swamped by sheer exhaustion. This finding is particularly true for those people the treatment is most intended to help: the less financially sophisticated, non-homeowners, and Black respondents.

On the other hand, linking the writing of a will to a less taxing interaction with the bank, such as opening an account, does improve intentions. The second issue is money. Money – in this case, $500 – increases the percentage of some individuals willing to write a will. The effect, however, is only half that associated with changing the timing from taking out a mortgage to opening an account overall, and mostly concentrated in those groups who do not need much more help in writing a will. So, getting the setting right is key. Finally, the impact depends somewhat on the characteristics of the individuals. Those who could be classified as more financially sophisticated – either by their responses or because they are already homeowners – tend to react somewhat differently to the alternative treatments than the unsophisticated. The impact also varies by race; Whites react more to the $500, and non-White individuals more to a change in setting.

Conclusion

Wills are important, particularly for lower-income and non-White households where the house is the major asset. So, incentives to increase will-writing could help reduce the racial wealth gap. While the notion of adding will-writing to the mortgage process turned out to be a bad idea, the survey and the experiment provide a lot of information on who writes wills and why, and they also suggest that setting matters and the effect of incentives varies significantly by individual characteristics.

References

Aubry, Jean-Pierre, Alicia H. Munnell, and Gal Wettstein. 2023a. “Can Incentives Increase the Writing of Wills? An Experiment.” Working Paper 2023-27. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Aubry, Jean-Pierre, Alicia H. Munnell, and Gal Wettstein. 2023b. “Wills, Wealth, and Race.” Working Paper 2023-10. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Contemporary Studies Project. 1978. “A Comparison of Iowans’ Dispositive Preferences with Selected Provisions of the Iowa and Uniform Probate Codes.” Iowa Law Review 63: 1041-1070.

Fellows, M. L., R. J. Simon, and W. Rau. 1978. “Public Attitudes About Distribution at Death and Intestate Succession Laws in the United States.” American Bar Foundation Research Journal 3(2): 319-391.

University of Michigan. Health and Retirement Study, 1996-2020. Ann Arbor, MI.

Endnotes

- 1Aubry, Munnell, and Wettstein (2023a).

- 2Aubry, Munnell, Wettstein (2023b).

- 3Fellows, Simon, and Rau (1978) and Contemporary Studies Project (1978).

- 4It is helpful to clarify what the results of these group regressions show and do not show. The coefficients indicate the extent to which participants in each group are more or less likely to write a will under Treatment 2 (+ $500) or Treatment 3 (“opening account” instead of “taking out a mortgage”) relative to Treatment 1. What they do not show readily is whether the responses of the two groups differ in a statistically significant way. It is possible to glean some information by looking at the magnitude of the difference of the coefficients of the two groups relative to standard errors, but the only formal way to determine a statistically significant difference is by estimating equations with interactive terms. Such equations are included in Aubry, Munnell, and Wettstein (2023a).