Medicare Trustees Report for 2023 Contained No Bad News

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

But expenditures remain high – primarily due to high health care costs, not program generosity.

This year I, with my sidekick Michael Wicklein, took a more-careful-than-usual look at the Trustees Report for the Medicare program. After all, Medicare – like Social Security – relies on payroll tax revenues, so it’s useful to understand the competing needs.

Traditional Medicare is composed of two programs. The first – Part A, Hospital Insurance (HI) – covers inpatient hospital services, skilled nursing facilities, home health care, and hospice care. The second – Supplementary Medical Insurance (SMI) – consists of two separate accounts: Part B, which covers physician and outpatient hospital services, and Part D, which covers prescription drugs. The arrangements are slightly more complicated because Medicare also includes Part C – the Medicare Advantage plan option, which makes payments to private insurance plans that provide both Part A and Part B services.

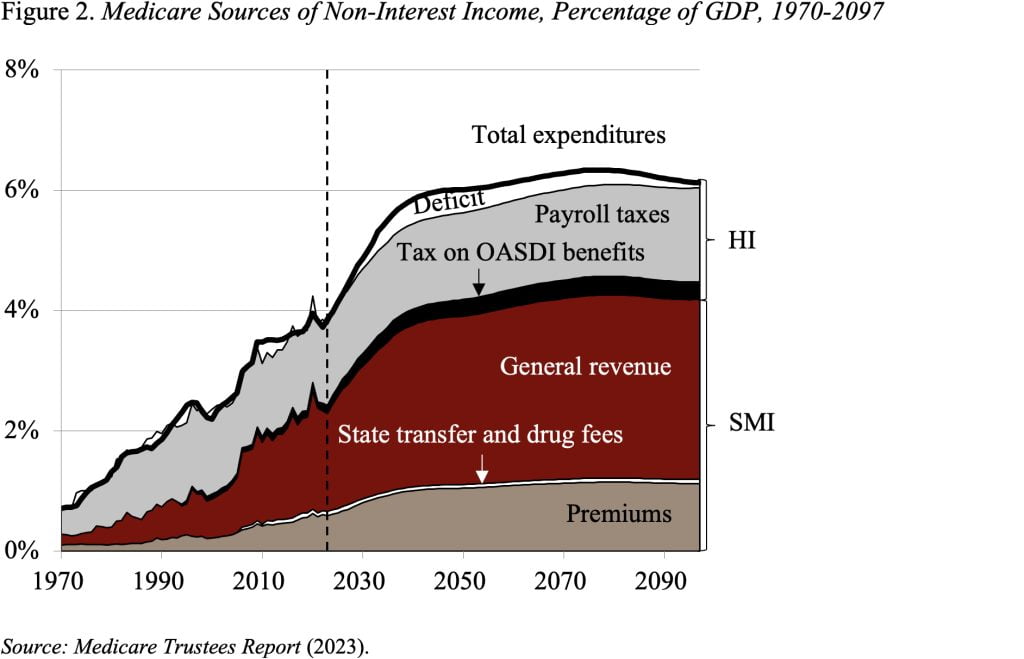

Each Medicare program has its own trust fund and its own source of revenues. Part A (HI), which accounts for 38 percent of Medicare expenditures, is the portion primarily dependent on payroll tax revenues. Parts B and D are financed primarily by general revenues, supplemented by income-tested premiums.

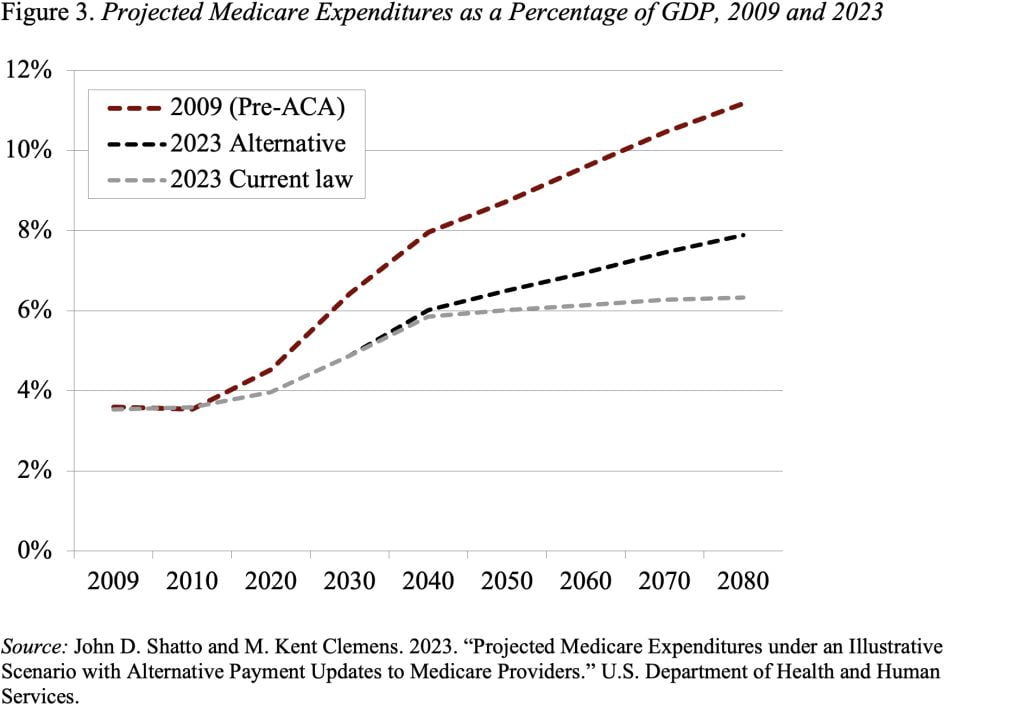

The Medicare Trustees issue an annual report projecting the program’s finances under current law. In addition, the actuaries prepare an alternative scenario that limits the extent to which Medicare payments to hospitals and physicians fall below those made by private insurers.

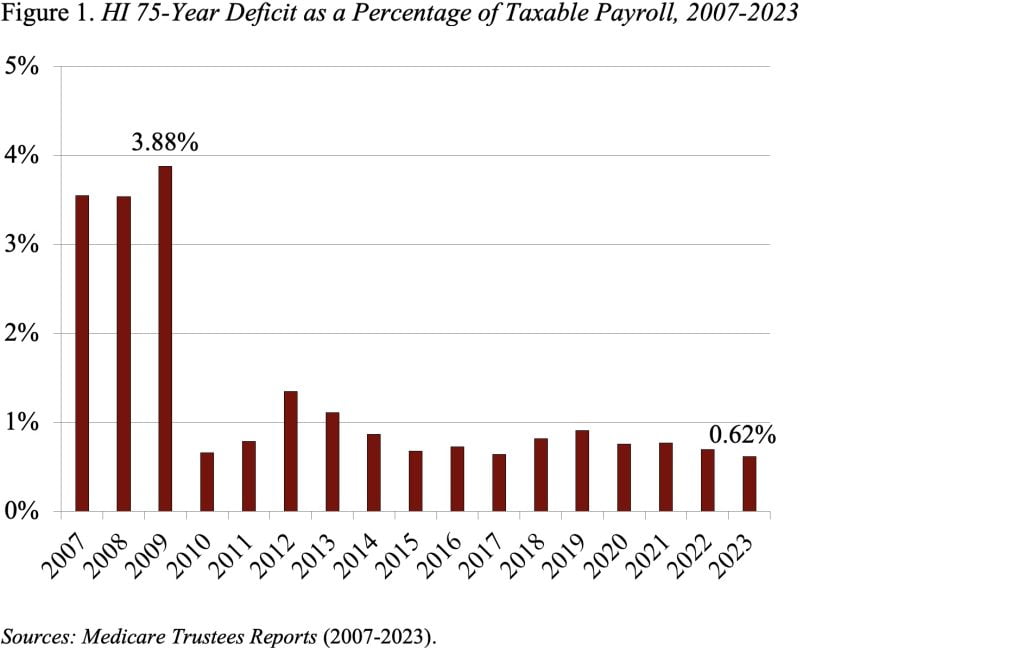

In terms of the HI program, assuming current law, the Trustees project a 75-year deficit of 0.62 percent of taxable payrolls. This deficit is actually at the low end of the diminished deficits that emerged in the wake of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) (see Figure 1).

For the HI trust fund to remain solvent throughout the 75-year projection period, the 2.90-percent payroll tax would need to be immediately increased by 0.62 percentage points. Social Security, which represents a competing demand on payroll tax revenues, would require an additional 3.44 percentage points to achieve 75-year solvency.

As the headlines indicated, the HI trust fund is projected to deplete its reserves in 2031. In that year, revenues would be sufficient to cover only 89 percent of program costs, so benefits would be reduced immediately by 11 percent. While the projected depletion is an action-forcing event for the Congress, the outlook has improved by three years since last year’s report.

Part B and Part D are both adequately financed for the indefinite future, because the law pro- vides for general revenues and participant premiums to meet the next year’s expected costs. Of course, rising premiums place a growing burden on beneficiaries (see Figure 2). Interestingly, these costs are also somewhat lower than in the previous report.

As noted, the actuaries also prepare an alternative set of projections that relax the cost-saving provisions in current law. Under these alternative assumptions, by 2090, the total cost of Medicare is about 2 percent of GDP higher under the alternative than under the current-law provisions. Note, however, that even these higher expenditures are way below the pre-ACA projections (see Figure 3).

The bottom line is that the 2023 Medicare Trustees Report contained no bad news. In fact, in Part A, the depletion of the HI trust fund was pushed out three years and the HI deficit was at the low end of post-ACA numbers, while expenditures for Parts B and D were actually slightly below those in the 2022 report. Moreover, Medicare’s demand on the payroll tax is modest compared to the increase required for Social Security. That said, Medicare does face significant financing challenges: it operates in a country with extraordinarily high health care costs and it has some serious gaps in protection.