Writing Wills May Help to Narrow the Racial Wealth Gap

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

If Black families wrote wills at the same rate as white, how much would it help?

Having a will is really important. In the absence of a will, a decedent’s assets are distributed according to state intestacy law. These rules work fine for traditional families, but can result in the wrong outcome when the intended beneficiaries are not related by blood, marriage, or formal adoption. Moreover, dying intestate is a particular problem when the estate is modest and the largest asset is the home, where heirs are often unable to coordinate on maintaining or selling the property – destroying value in the process.

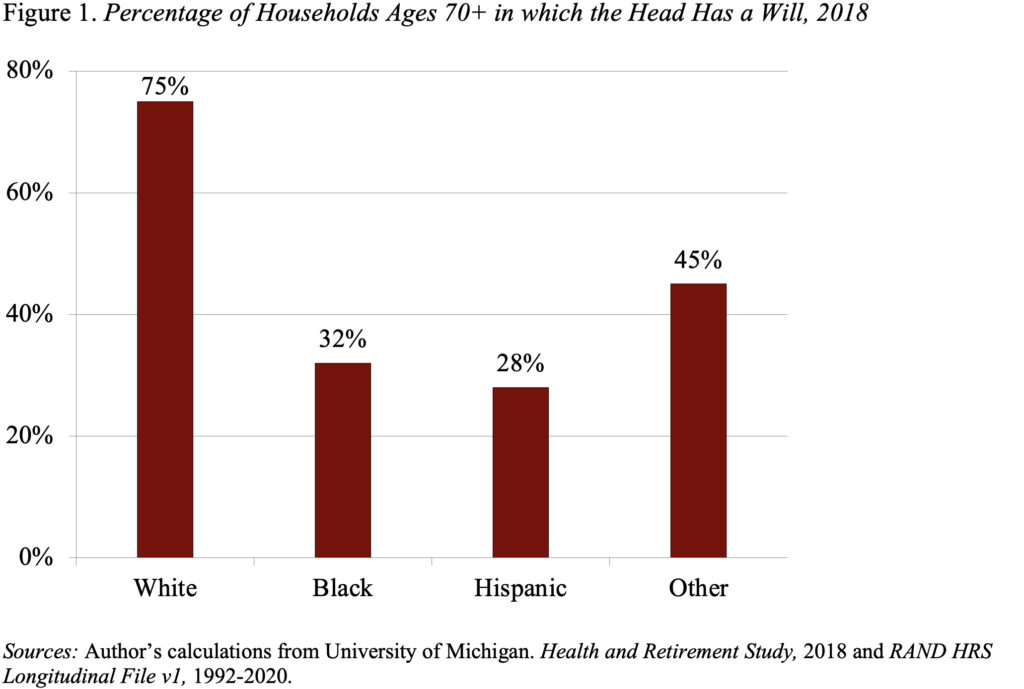

Despite the advantages of having a will, will-writing varies dramatically by race. Black, Hispanic, and other minority respondents are much less likely to have a will than their White counterparts (see Figure 1). This pattern is not surprising given that having a will is related to having received an inheritance, and non-White households are significantly less likely than their White counterparts to receive an inheritance, even accounting for education, age, and marital status. This negative cycle of lower inheritances and lower will-writing by Blacks contributes to the gap in wealth between Black and White households that has plagued the United States for more than a century.

Given the importance of will-writing on savings, bequests, and maintaining the value of transferred assets, we wanted to see how much equalizing will-writing rates between Black and White households would have narrowed the racial wealth gap over the past few generations.

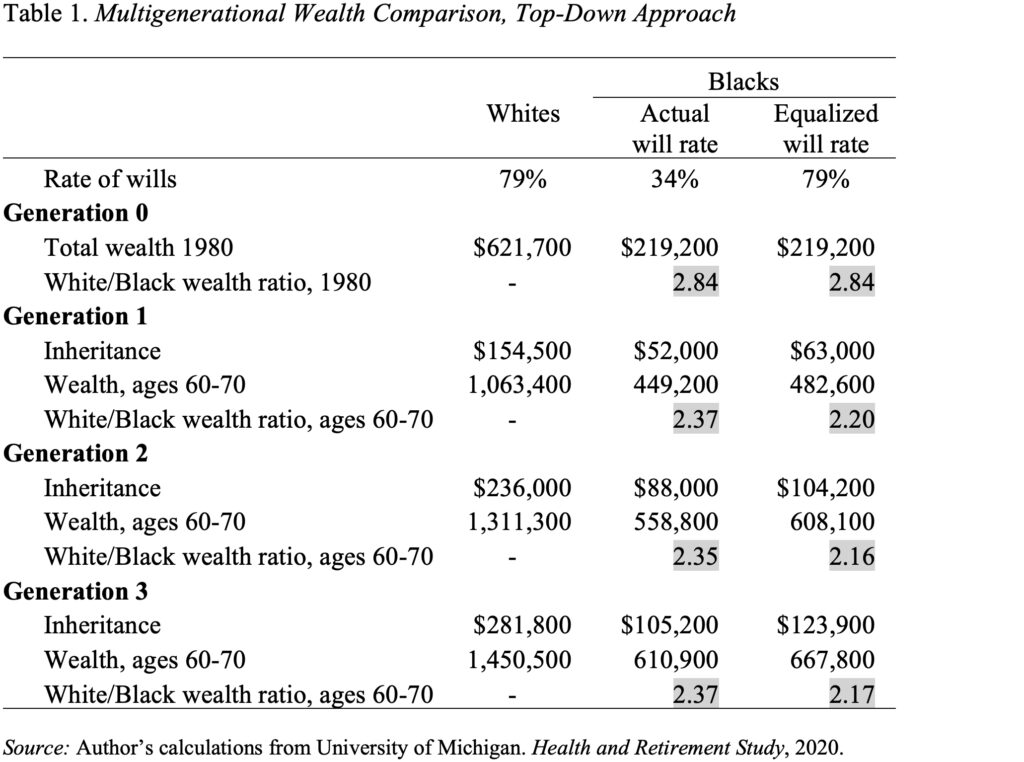

The analysis starts with an initial White-Black wealth gap estimated as of 1980 for households with a head ages 60-70 – when households are enjoying their peak lifetime wealth – and then tracks the wealth of representative White and Black households over three 20-year generations – 2000, 2020, and 2040. The estimates of wealth across generations rely crucially on two equations: 1) the relationship between inheritances and late-life wealth; and 2) the relationship between late-life wealth and bequests. With the coefficients from these regressions in hand, we calculated the bequest from each generation to its subsequent generation under two assumptions – actual White and Black will-writing rates and then assuming Black will-writing rates equaled those of Whites.

The results are shown in Table 1. (I know that it’s a lot of numbers, but wanted you to see the iterative process.) In Generation 0, the ratio of White-to-Black wealth is 2.84. Assuming that the percentage of households with a will remains at 79 percent for Whites and 34 percent for Blacks, the White/Black wealth ratio ends up at 2.37. On the other hand, if the will-writing rate for Black households is increased to that of Whites – that is, from 34 percent of households to 79 percent – the White/Black wealth ratio is 2.17.

In short, the results show that had will-writing rates been equal for Black and White households over the last three generations, the White/Black wealth ratio would have declined by 10 percent – a modest but meaningful reduction. Alternative estimates yielded very similar results. We think that these results make a convincing case for interventions to increase will-writing of Black households.